ON RAISING DAUGHTERS

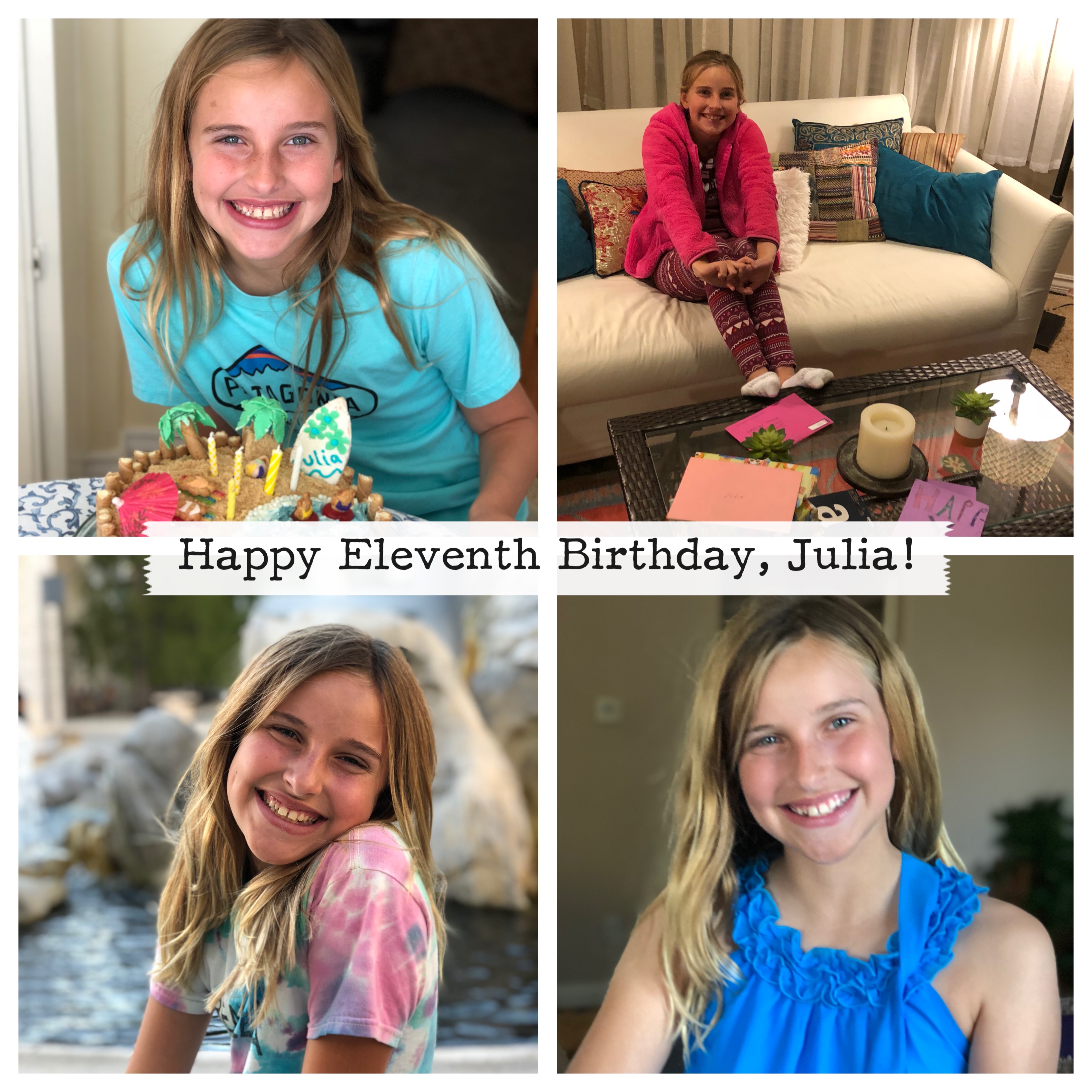

Two summers ago when she was preparing to start fourth grade, I read Romeo and Juliet with my oldest daughter, Julia.

It took a long time to read each line and to examine closely the Elizabethan era prose/verse, and to discuss characterization and what Shakespeare was trying to do at that point in the play. After we had spoken the lines out loud and chewed over their meaning for some forty minutes, we would watch professional actors bring the action to life. We watched all of the Franco Zeffirelli’s 1968 version and also Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 version.

Julia loved it! Each night she begged to read and watch more. The movies especially helped. (The action in the play forced me to do some extemporaneous sex ed so that Julia could understand what was happening between the two lovers offscreen.) But our reading together of Romeo and Juliet was an unqualified success.

It did not hurt that I had taught Romeo and Juliet sixteen straight times to high school freshman before I taught it to Julia. I know that play backwards and forwards. I love it. Despite having taught it to so many times to so many students, I am not in the last bored with it.

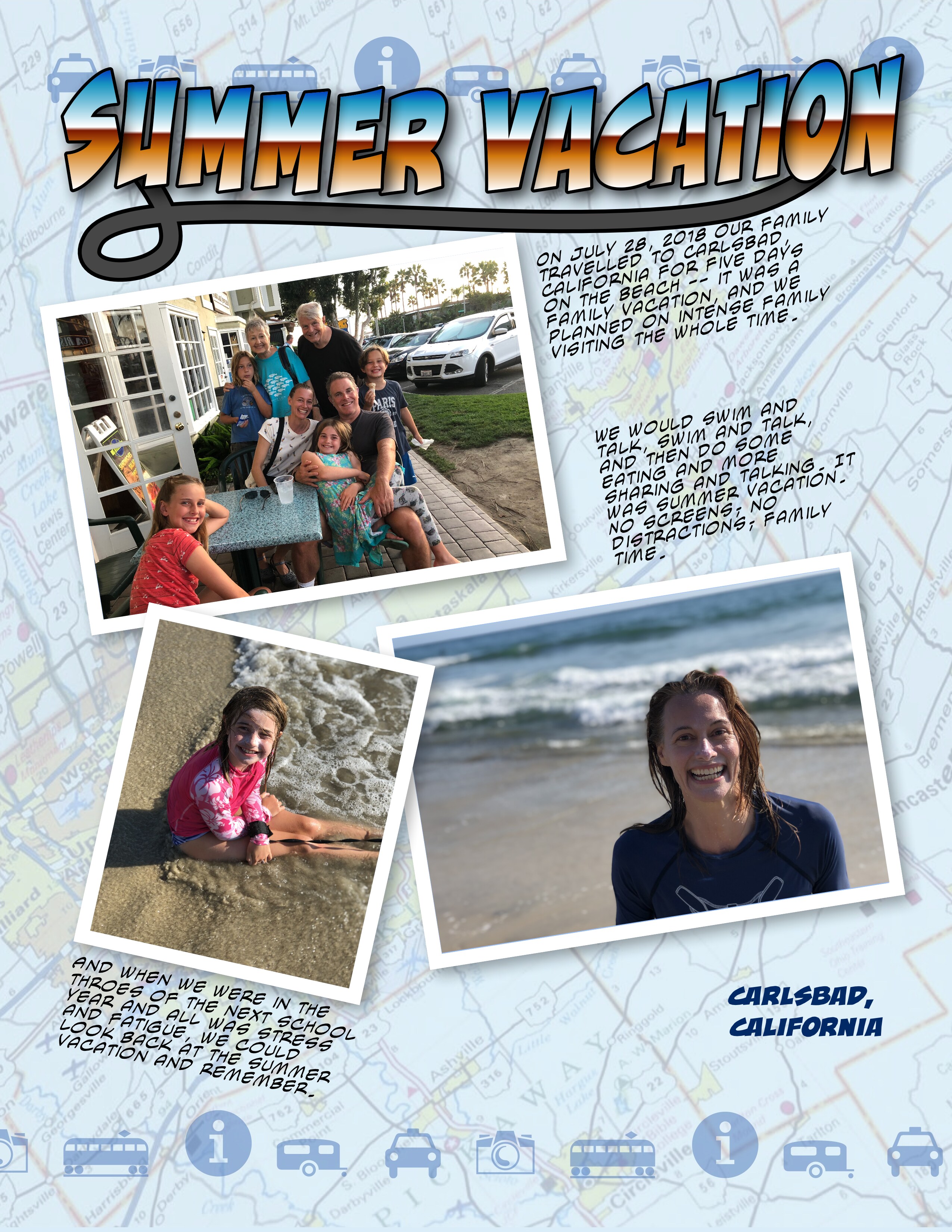

This summer as Julia approaches sixth grade and middle school, we attempted to read Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. I have been waiting for more than a decade to read this book with her, and finally this summer the time was right, I thought. We would read a chapter or two together, and then we watched the action from those chapters from Joe Wright’s superb 2005 movie version of the book. As with Romeo and Juliet, the movie was crucial in bringing to life visually the more abstract events taking place on the written page. Austen’s plot necessitated me explaining much to Julia about social class in aristocratic early 18th century England, as well as the limited financial prospects unmarried women faced at that time. We made good progress through the novel. Julia understood and enjoyed the action of the plot, but we bogged down. Reading this novel during summer vacation had to complete with the going to the beach and swimming in the ocean. Julia’s enthusiasm to sit down and read began to flag. She grew reluctant to wade into the shadow conflicts chapter after chapter between Darcy and Elizabeth Bennet, and I was reluctant to insist she do it. This was supposed to be fun; I did not wish to flog Julia to the end of the book, like a rider whipping an exhausted horse to the end of a journey. Fine literature should be a pleasure, not a chore — at least most of the time.

So one evening I grew impatient and read the second half of the novel by myself: those were a particularly delicious few hours. I decided to give up with Julia and the novel. So without further ado we put the book aside and watched the rest of the movie together. Julia enjoyed the movie, even if she had not read the whole book. I told Julia that when she was older and ready, she could read the book all the way through by herself. I have no doubt she will do so. At 11 years of age Pride and Prejudice might have been too much for Julia, even when her father was reading it out loud and explaining it to her. However, in a few years Julia will have the patience, stamina, and skill to read such books not only with understanding but with pleasure. When she is full grown, Jane Austen will not defeat her.

So a part of me considered the project a failure, since we failed to finish the book. I felt pain in thinking this. But getting halfway through Pride and Prejudice was also a solid foundation upon which to build — and to enjoy ultimate success later. So the summer Jane Austen literature project also was a success of sorts.

And this brings me to the point of this essay: the parental drive to impart specific values to offspring. I see what is important in life and human relations, and I hope to inspire a similar vision in my daughters. I have seen religious parents do this with their children, mostly with success. They try to get them to share their devotion to the one true God and His word. I have also seen it with politically partisan parents, with somewhat less success. They try to get their children to share their passion for what politics should be, in their opinion. Is this desire to shape the worldview of one’s children a species of vanity by parents? Or is it a natural attempt to explain and bring children into the value structure of their family? Or both?

I had no burning political passion to convert my daughter to one partisan cause or another. Nor had I religious convictions that were important to me, and so then would become important to my daughters because I would make it so. I sometimes worried about this lack of an animating, incandescent cause might mean my daughters could lack conviction and backbone when they arrive to adulthood. What did I stand for? What about our family? The old adage claims that “when you stand for nothing, you fall for everything.” Without a proper value system, how might my daughters navigate ethical dilemmas and know what is right? How one should live?

But as a parent, I have to be true to myself. I received most of my moral instruction not from the Bible that I was force-fed as a youth but from the literature I devoured. I did learn from the sufferings of Job, the wanderings of Moses, and the teachings of Jesus that my Catholic upbringing taught me. But my attention and imagination was much more captured by Gandalf and Frodo, Anna and Vronsky, Pip and Ms. Havisham, and Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth Bennett. I learned from Sophocles and Seneca, Abraham Lincoln and Henry David Thoreau, and John McCain and Christopher Hitchens. I sometimes lament that I have not much to offer to my daughters for instruction other than intense exercise to strengthen the body and fortify the spirit, and a love of literature and history for ethical and intellectual formation. But if that is all I have, it is not nothing!* I suspect I raise my daughters more like an educated pagan than a good monotheist — I yearn towards Athens and spurn Jerusalem. I preferred a broadminded pagan Rome to a prosecutorial Christian Rome. It would pain my devoutly Catholic father to hear these words. But so it is. I must be true to myself, as a son and a father.

I lack the fanatical, true-believer gene that inspired the initial Puritans to persevere while starving in frigid “New England,” or the persecuted Mormons who fled for their lives and walked across the freezing plains of North America pushing handcarts to Utah. (“If God be with us, who can be against us?”) I abhor dogmatism and dogmatists — the fanatacism of the single-minded. My interests are many, and if forced to on a job application form I would copy Jim Svejda of KUSC and write Mozart’s name in the box marked “religion.” But that is more an abiding passion than a religion. I am skeptical by nature and hesitant to claim too much of anything. But if I do not have the one true God-intoxication of the monotheists, or the similarly demanding religion that some have made out of politics and cries for social justice, I would argue that I have as strong a cause for living a worthwhile life.* I love this quote by Lynne Kelly,

“Some believers accuse skeptics of having nothing left but a dull, cold, scientific world. I am left with only art, music, literature, theatre, the magnificence of nature, mathematics, the human spirit, sex, the cosmos, friendship, history, science, imagination, dreams, oceans, mountains, love, and the wonder of birth. That’ll do for me.”

All those interests — art, music, history, literature, friendship, sex, love — how can one ever be bored? That is how I see it. It is who I am, as a father and in everything else.

Is not this evident in even a cursory perusal of my personal webpage?

So this brings me back to Pride and Prejudice. I have been waiting for more than a decade to read this novel and use it as a didactic tool. “A tool towards what goal?” you might ask. A tool for showing my daughters what it means for a young woman to fall in love. To combine the physical desire for a man’s body with the intellectual respect for his character and decency — to be Elizabeth Bennett with her Mr. Darcy — for tenderness, trust, intimacy, commitment, marriage — “grown up love.” This is what I hope for my daughters. It is as was said of Shakespeare’s Cordelia: “She is herself a dowry.” To have such daughters I hope so much. I will do all I can.

I was crying when I watched in the movie Elizabeth’s father, saying to her “I could not have parted from you. my Lizzie, for anyone less worthy.” The bond between father and daughter. You walk your daughter down the aisle during her wedding to the to the waiting groom. Her adult life awaits; the father has done what he could. The message of the novel is powerful and clear: man and woman are lost without each other. They are so much stronger the one melded with the other, as Darcy and Elizabeth show so well, once they abandon their pride and prejudice.

To learn how one should live from a thousand different novels and poems is a more subtle and complicated business than reciting and obeying the Ten Commandments, but my moral formation has been and continues to be in literature. Sure, the Bible is literature, but it is only a small portion of the corpus of human knowledge.

My daughters, my beloved daughters….

When I look around at the world that surrounds us, what do I not want for my daughters – or myself, for that matter?

I don’t want her to be playing online video games like Fortnite hour after endless hour, as do so many of the children of my friends. I don’t want her to be much occupied by the trending topics and frivolous memes found on social media — diving down into that digital rabbit hole that will take up so much of her time and provide so little lasting enrichment or happiness — superficiality and surface appearance — worrying about how many “likes” her Instagram postings get — forever busy hopping from place to place on the Internet, as her attention is affixed to a new set of pixels on a screen every few minutes.

I want for my daughters quiet and introspection, the ability to nourish their inner light. I want them to be aware of the sun overhead and the wind rocking the trees in the distance. I want the sustained interior attention of a reading culture, not the distracted inattention of a digital culture. I want my daughters to have the print culture I and many previous generations grew up in, and not so much the culture of unbridled technology Google and Facebook would want her to grow up in.

When I turned 18 and told my parents I did not want to go to church anymore, my mother told me my decision did not trouble her as long as I did not neglect my spiritual life. My mother, devoutly Catholic in her own idiosyncratic way, was telling me that “man does not live by bread alone, but by every word of God.” I understand what she was telling me. I flatter myself that I could respond and tell my mother I have not let my spiritual life lay fallow, even if I have rarely gone to Catholic mass. I would want the same for my daughters. To nurture the self. To look deeply inwards. To then engage outwards and perform noble acts. To have purpose and direction. To live a life worth living.

A handful of times over more than two decades of teaching I have been so impressed by a female student that I wrote “you are yourself a dowry” in my parting words to her. The young woman was beautiful, intelligent, classy, deep-thinking, sensitive, ambitious, kind, caring — everything a man would want in a woman. It was almost the highest compliment I could pay her.

How I hope to say the same thing about my own daughters!

And towards that goal let me direct my fatherly efforts — this summer, and forever always.

Amen.

* P.S. I have written earlier about how I am an agnostic, and care little about God or the tenets of Christianity. In matters of faith, I am indifferent. But I was raised and married in the Catholic Church, and I hope to be buried in it. I do not reject the religion of my family, nor do I ostentatiously refuse to step foot in a church, as some I have known do. If I am a rebel, I perform the role quietly. I try to be a “gentleman” as described by John Henry Newman —

If he be an unbeliever, he will be too profound and large-minded to ridicule religion or to act against it; he is too wise to be a dogmatist or fanatic in his infidelity. He respects piety and devotion; he even supports institutions as venerable, beautiful, or useful, to which he does not assent; he honors the ministers of religion, and it contents him to decline its mysteries without assailing or denouncing them. He is a friend of religious toleration, and that, not only because his philosophy has taught him to look on all forms of faith with an impartial eye, but also from the gentleness and effeminacy of feeling, which is the attendant on civilization.

Not that he may not even hold a religion, too, in his own way, even when he is not a Christian. In that case his religion is one of imagination and sentiment; it is the embodiment of those ideas of the sublime, majestic, and beautiful, without which there can be no large philosophy. Sometimes he acknowledges the being of God, sometimes he invests an unknown principle of quality with the attributes of perfection. And this deduction of his reason, or creation of his fancy, he makes the occasion of such excellent thoughts, and the starting-point of so varied and systematic a teaching, that he even seems like a disciple of Christianity itself. From the very accuracy and steadiness of his logical powers, he is able to see what sentiments are consistent in those who hold any religious doctrine at all, and he appears to others to feel and to hold a whole circle of theological truths, which exist in his mind no otherwise than as a number of deductions.

— which means that, despite it all, perhaps I am not entirely irreligious.

September 19, 2018

Dear CC,

Hello! My name is Richard Geib and I am Julia Geib’s father. I am writing to ask some help of you for my daughter, a new arrival to your middle school.

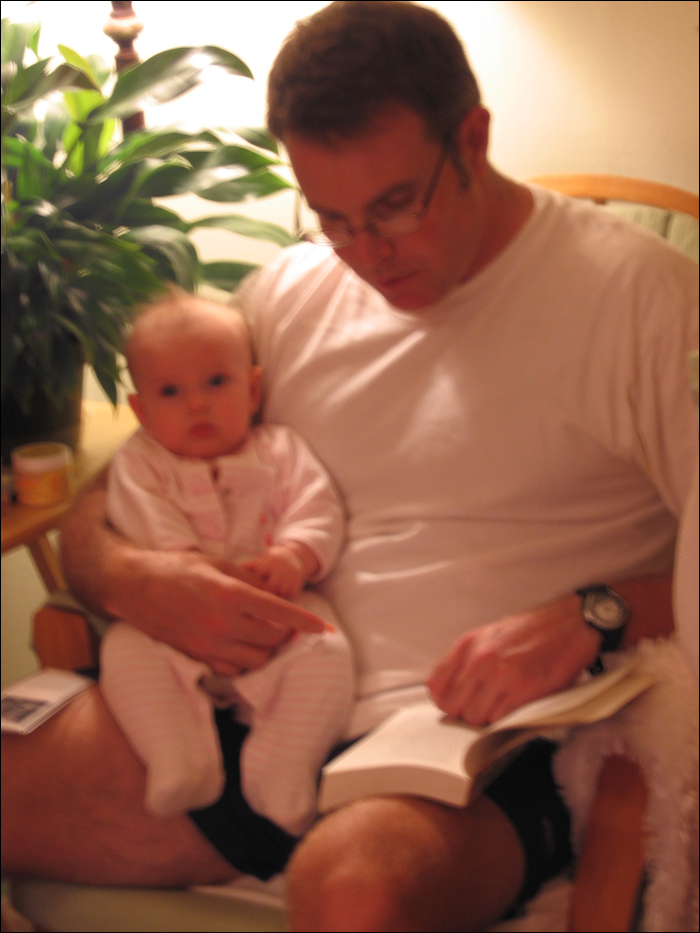

Literature has been an important part of Julia’s life almost since she was born. In particular, we read intensely to baby Julia, and she has also listened to audio books almost every night while going to bed for almost nine years. I read every single Harry Potter book to her by the end of second grade; Julia read them all to herself in third grade.

I recently did a Google search of what books middle schoolers should read. Most of the books I saw — Hunger Games, Allegiant series, School of Good and Evil, Percy Jackson, Series of Unfortunate Events; and many others — Julia has already read. There are a number of books that come to mind for Julia to read, but she has somewhat resisted me. I urge her to read more mature fiction, and I think Julia can do it. I want her to stretch herself. But she is only 11 years old and in sixth grade, I realize.

This is where we could really use your help, Cece. If you could please guide Julia, as far as possible, into quality middle school literature, Maria and I would be most appreciative. There is nothing wrong with “junk food” literature, once in awhile, but the mind wants something more filling and substantial. Something healthier.

Some of the books I was thinking of were —

- Little Women

- A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

- Anne of Avonlea

- Lord of the Rings trilogy

- Chronicles of Narnia (Julia read these in 2nd grade, I think, but I think much of it went over her head)

- The Yearling

— but you are the expert in middle school literature, so we will accede to your recommendations and guidance.

Julia will pretty much read anything you give her.

And Maria and I will be so thankful for any help you can give to Julia.

Very Truly Yours,

Richard Geib

Reading “Paradise Lost” back in 2007 to five month old Julia; at the time, she seemed indifferent to Milton.

“What in me is dark

Illumin, what is low raise and support;

That to the highth of this great Argument

I may assert Eternal Providence,

And justifie the wayes of God to men.”