It was approximately 3:17 pm when we arrived at Adolfo Camarillo High School with my boys high school tennis team. Our team arrived in two vans, with the name of our school on it; it was obvious who we were and why we were there. But the security guy at the guard checkpoint at the front of the school was skeptical.

“Who are you? What time are you expected?” After a short discussion on his radio while we waited, he told me, “You are 45 minutes early for your 4:00 p.m. match. Why don’t you go to the nearby Starbucks and park there until that time?”

My blood pressure started to go up. I knew this guy was a lowly-paid worker bee who didn’t make the rules, but still. I told this twenty-something year old kid the following:

“The match is scheduled to start at 4:00 p.m. and warm-ups are at 3:30. If you let us in, we can park and get to the tennis courts on time to warm-up.” We were not early. We were right on time.

We sat there as he made more radio calls to the assistant principal and the athletic director. Finally, Mr. Minimum Wage let us through with complicated instructions as to where to park. I drove inside the main gate, and then I came up to another gate which I could not pass through, as I did not have the code to open it. So we just parked there for a bit wondering what to do next. I was not sure what to do. I had never been to Adolfo Camarillo High School before.

Finally, I drove back out the main gate and went to a secondary gate. I got through that one and drove through a series of areas until I could see the tennis courts in the distance. We skirted a tall black wire fence on the perimeter of the school, as we felt our way towards whatever exercise areas we could see. Soon another twenty-something security guard caught up to us driving a golf cart. She showed us where to park, and escorted us on our walk to the tennis courts.

“Wow, Coach, this school feels like a prison!” one of my athletes said as we navigated around the series of fences in the school vans. I totally agreed. Even inside the large main fence, the basketball courts for PE were surrounded by interior security fences. Fences inside of fences. Security guards in golf carts. Radio chatter bantered back and forth.

Back in the early 1990s, I worked briefly at the Orange County Central Men’s and Women’s Jail. So I know what jail life looks and feels like. Camarillo High School – with sturdy inside fences behind taller outside fences, crowds of people viewed through the layers of steel links of multiple fences, and guards walking around with radios – is what jail feels like.

This high school was in an affluent neighborhood, in a school district whose other high schools were in poorer areas with higher crime. But still. Was this necessary? Turning high schools into security-laden facilities? Layers of big fences opened by codes? Checkpoints on the outside of the fence with security guards just to gain access to the main parking lot?

This is what school boards are choosing to do in the age of school shooters, I realized at the time. They are turning schools into more “hardened” facilities focused on safety and control, and the end result is a campus where students receive their educations and teachers teach in places that feel like jail.

Is this what it has come to? Education has evolved into this?

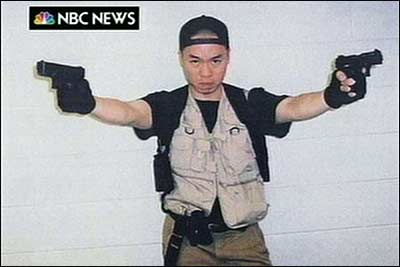

The country has been terrorized in the past few decades from very rare but very spectacular school shootings where isolated wingnut psychopaths have murdered their peers on campus. This might mean high school students coming to school with guns and/or bombs, like in the infamous Columbine or Stoneman Douglas attacks. Or it might mean an attack on an elementary school, like at Sandy Hook or at Uvalde, where a deranged gunmen targets young children for murder, just about the worst crime one can imagine. But there is the one commonality in all these attacks: the assailants are doing it for attention. They want to be acknowledged. In the past losers used to spray-paint on the walls their graffiti tag – “I might be poor, unknown, and going nowhere in this world; I know it. But look at my graffiti tag and know I exist! I have value in the public view, even if it is only this ugly scrawl on the wall.” GIVE ME ATTENTION!

There is a similar thinking with the the isolated loser who goes on to commit murder-then-suicide while performing a lurid crime for attention. “I struggle in ignominy and isolated misery, but tonight after I do this deed and I’m dead everybody will know my name! I’ll be INFAMOUS, which is the next best thing to being FAMOUS!” LOOK AT ME!

It is pathetic. But the mass shooter meme has gone viral, starting with the Columbine Massacre (and maybe earlier), with successive copycat imitators, researching and seeking to surpass earlier mayhem. This seems to be the world we live in. It is terrifying. Who can say when this mimetic performance will have worn out its cultural moment? When the page will turn and there will be no more school shootings? When murdering to gain notoriety and press attention will be over? I have no idea, but I suspect not anytime soon.

Look at these school shootings in the United States – Columbine, Sandy Hook, Majory Stoneman Douglas, Uvalde; and more on college campuses – Virginia Tech, Umpqua, Isla Vista, University of Virginia, Michigan State.

I remember after one of these horrible senseless attacks (they begin to blur together) a fellow teacher confided to me, “I don’t know about this, Richard. I’m not sure I signed up as a teacher to get shot in my classroom.” I told her that statistically-speaking, we teachers are much safer in our classrooms than outside them. But the cold facts might not outweigh the sense of fear (panic?) that copycat mass shooting events hold on the popular imagination. This is nowhere more true than in our schools.

So it is the desire for ATTENTION which leads isolated weirdos to shoot up their schools in rare but spectacular crimes – the desire for fame and attention, that whore of pop culture societies, as Chris Rock so well explained:

Anything from social media down… LOOK AT ME!

These ATTENTION-seeking mass shooter crimes lead to FEAR, and that FEAR leads schools to build tall fences and turn campuses into something more resembling prisons. I get this. I asked my 16-year old daughter about fortifying campuses and attending classes in a school behind a series of tall fences, and she said it did not trouble her. “If it helps keep me safe, I don’t mind.” It did not seem to bother her.

But it does bother me. I don’t think I could teach in a place like Adolfo Camarillo High School. Maybe the staff and students there are used to going to school like this, but I’m not. I teach at a magnet school which is famous for having fewer discipline problems, less campus rules, and a more relaxed vibe. A person can walk right onto campus or park without being challenged by security. This is how a school should be, in my opinion. We focus more on teaching and learning, less on securing and controlling. It is a smaller school. It works.

But perhaps tall fences, guard checkpoints, and more security are the future of American schools.

If so, I want nothing to do with them.

Thank God I am only a few years away from retirement!

I remember as an undergrad taking political science classes at UCLA about terrorism 35 years ago from the renowned professor David Rapoport. He would explain that the larger goal of terror groups of that era (Baader-Meinhof Group, Red Brigades, Weather Underground, Japanese Red Army, etc.) was to kill a few people from a democratic nation, terrorize millions of others thereby, force the government to curtail civil rights for all, and hopefully bring about a violent proletariat revolution from below. Security was one concern of a democratic society, but freedom was no less a concern, Professor Rapoport explained. And if an elected government overreacts to a terrorist act and voluntarily abridges the civil rights of its citizens too much, then the terrorists have won – they have been the catalyst for a democratic society undermining its own values. A handful of violent zealots can kill only a relatively small number of innocent people in a terrorist attack (the more spectacularly, the better, à la 9/11), but only the government can infringe on the rights of the entire population. Terrorists can’t do that.

The tough problem is identifying where the government’s desire and power to keep people safe conflicts with their ability to enjoy freedom and their civil rights. In reality, it is always a difficult balancing act. Look at the following Ben Franklin quote, “Those who would give up essential Liberty, to purchase a little temporary Safety, deserve neither Liberty nor Safety.” I never liked that quote. It seems to me that any society – or school – is always weighing the desire for liberty with the needs for safety. But maybe it comes down to what is “essential Liberty” in any specific situation? What exactly are you giving up in the name of “safety,” and is it worth it? What might be the tradeoffs? Saudi Arabia and Communist China are “safe” countries, as long as you don’t run afoul of the authorities, but not many Americans would want to live there. Those are unfree countries with little regard for personal freedoms. They are dictatorships. Control and order are the point. To a fault.

But let’s return closer to home in Ventura County, California at Camarillo High School in the Oxnard Union High School District. Do all these extensive/expensive fences and guard checkpoints increase safety on that campus? Well, it will be very difficult for an intruder to get on campus without passing through safety checks and having permission to enter. “Coyotes will have difficulty getting on campus here in the middle of the night,” I thought to myself. Organized terrorist groups or disaffected lone-wolf shooters will have to be highly trained to break into Camarillo High School. They will need to bring powerful bolt cutters and/or explosives to break through the fences. Staff and students can rest easy on that score.

But thousands of students come on campus and leave everyday at Adolfo Camarillo High School. Could one of them still bring a gun onto campus? With all the security installed, do students also walk through metal detectors? Are they frisked upon entrance to the school? Are their backpacks and sports bags searched? If some disturbed student wanted to smuggle a gun onto campus, would these fences make a difference? Is the enormous expense of money for fences and “other safety measures” worth it? The setting the tone on campus of security and control? Does this contribute to the learning environment? Or does it do the opposite? Might all this increased security be counter-productive? Is it a waste of money? Have we changed our campuses to resemble jails with no real increase in security?

As a teacher I have struggled to reconcile a police presence (“school resource officers”) semi-continually on campus, but so it has been for the almost four decades of my teaching career in public schools. Police have become a relatively common sight on campus, and staff and students often know the “School Resources Officer” (SRO) by name. I don’t remember ever seeing law enforcement on campus when I was a kid going to school in the pre-Columbine massacre era. But I worked as a teacher after that terrible bellwether 1999 attack in Colorado, and I was still able to do my job with SROs around campus in the post-Columbine era. Our SRO is named “Matt,” and I have a professional relationship with him going back years. He is a good guy.

I have heard critics call for the removal of SROs from public schools, claiming that it encourages the “school to prison” pipeline in society. It depends on the need, in my opinion. As I see (and saw) it, many schools in low-income areas are surrounded by communities with multi-generational gang families, and they send their offspring to schools plagued by crime. Tight security on campus in this context might make sense; not having it might be plain ol’ negligence. And having a cop available who can attend to whatever issues might arise could be a good idea in all schools. But it would be easy to take it too far and this is what is happening, in my opinion. School boards all around the country, panicking over isolated school shootings, are buying the infrastructure to “harden” schools and turn them into fortress-like places – in the name of stopping this lightning-strike chance of a school shooting. I don’t like it.

But who knows?

If schools in gang areas have tons of gangmembers on campus with tons of crime, maybe it is reasonable to bring in tons of security.

And maybe if average everyday schools DO have students who might possibly be disposed to bring a gun to school to shoot their fellow students and teachers, then maybe we should turn out campuses into jail-like places with security guards and tall fences. Perhaps that is logical. It might be the right step to take.

But I don’t want to teach there. Because I don’t want to live or work that way. This might be a bridge too far for me as an educator. As Robert Frost explained, “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall.” The Great Wall of China, Berlin Wall, Maginot Line, Trump’s call for a wall on the Mexican border – they are the creatures of FEAR, in my opinion. They are tokens of cultural decline.

I have listened to critics of the public school system with mixed feelings over the decades. John Taylor Gatto, an award winning teacher, claimed back in the 1990s that American schools were utterly unrepairable and “school should be abandoned.” Gatto turned his back on public education forever, quitting his NY city teaching job in frustration and urging everyone else to do the same. Gatto is way too extreme, in my opinion; his argument to walk away from it all is laughable. Then there were other critics who claimed public education was a “school to prison pipeline” which was fundamentally inequitable. Such critics had a bit of a point, but I disagree. Now there seems to be the argument “TURN EVERY SCHOOL INTO A HARDENED BUNKER TO KEEP SCHOOL SHOOTERS OUT.” No, thank you. Can’t do it. This is the hill I might choose to fight and die on.* I become a school critic myself then.

If my high school takes that road, I’m out. If the place begins to resemble a jail, and if it feels like one inside, I can’t work there.

I’m embarrassed for Adolfo Camarillo High School and the Oxnard-Union High School District which runs it. I read that then Oxnard Union Superintendent Penelope DeLeon explained in 2019 that the school district paid for and installed these “security upgrades” “in response to incidents of school violence reported throughout the country.”

“We want to control who comes in and out of our schools,” DeLeon said.

(citation)

To the School Board:

What are you doing?

Is it worth it?

Are you sure?

What are the costs? Financial and otherwise?

Are there trade offs involved with all this security? Is there no other way?

Are you turning your schools into jails?

* It is no secret I am a gun-guy and 2A advocate. But I am far from a fan of arming teachers in schools as a defense against disaffected school shooter-type losers in search of notoriety. But rather than cowering behind fences in fear, if the threat REALLY is that real, I would be in favor of arming teachers who are willing and able. If things have REALLY gotten to such a point – and I don’t think they have, after looking at the numbers and weighing the risk – maybe that would be a smart policy. Maybe. But cowards place their faith in walls, Maginot or otherwise, and those walls often fail them. King Agesilaus II of Sparta, in contrast, claimed the walls of his city-state were his young men, and his borders the tips of their spears; he placed his faith there. If the threat gets to that point, I go with the Spartans (Hómoioi), not the French (Maginot).

4 Comments

Dave

You could see yourself carrying a gun at work?

rjgeib

Not a fan of the idea. Don’t think it is necessary. Very much prefer not to. Not going to.

Over 28-years in the classroom I’ve never had need of putting hands on anyone in anything resembling a violent incident, and I don’t expect to moving forward.

Anonymous

You work in a nice school with generally good students. You are spoiled. The rest of the world is not like that. Recognize and apologize for your privilege.

Jay Canini

I don’t see why Mr. Geib needs to apologize for his privilege. I mean I agree that recognizing privilege one has and doing one’s best to help the less privileged are both good, but I fail to see why he has to apologize for it.