In his biography Open the tennis champion Andre Agassi said the following, “A win doesn’t feel as good as a loss feels bad, and the good feeling doesn’t last as long as the bad. Not even close.” This is a way of saying that we respond more powerfully to a negative stimuli than to a positive one. Maybe this is an evolutionary maneuver to help to try and keep us alive in a hostile world. But if so, it unfairly accentuates the negative over the positive. It leaves us prioritizing the half empty glass rather than the half full one.

Take Agassi, for example. Why should a painful moment of bitter defeat on the tennis court remain palpable decades later? Why is that more powerful than a corresponding moment of triumph? That is what can happen.

Andre Agassi won eight grand slams and is one of the most famous tennis players of all time. He first won Wimbledon when he was 22-years old, came back after two sets down to win the French Open in 1999 against Dimitri Medvedev, and crushed his rival Boris Becker at the 1995 US Open. He made amazing amounts of money. That was the good. But there was also the bad. The bitter defeats Agassi suffered: the loss to Pete Sampras in the 1995 US Open finals, or all those Wimbledon losses also to Sampras, or the stinging defeat to Patrick Rafter at the Wimbledon semis in 2020. These losses seem more emotionally resonant to Agassi than his victories were. The defeats hurt more than the victories thrilled. Why? Does it have to be that way?

A quick web search gives me this explanation:

“Negative differentiation states that since negative events are more complicated than their positive counterparts, we require a more significant mobilization of cognitive resources to minimize the event’s consequences and deal with the experience, making it a more memorable and intense experience.”

The Decision Lab

Sometimes this is referred to as the “negativity bias.” It favors the painful over the pleasurable in the human mind, and it’s an insightful observation about the human condition, albeit a sobering one.

I have seen it in my own life lately.

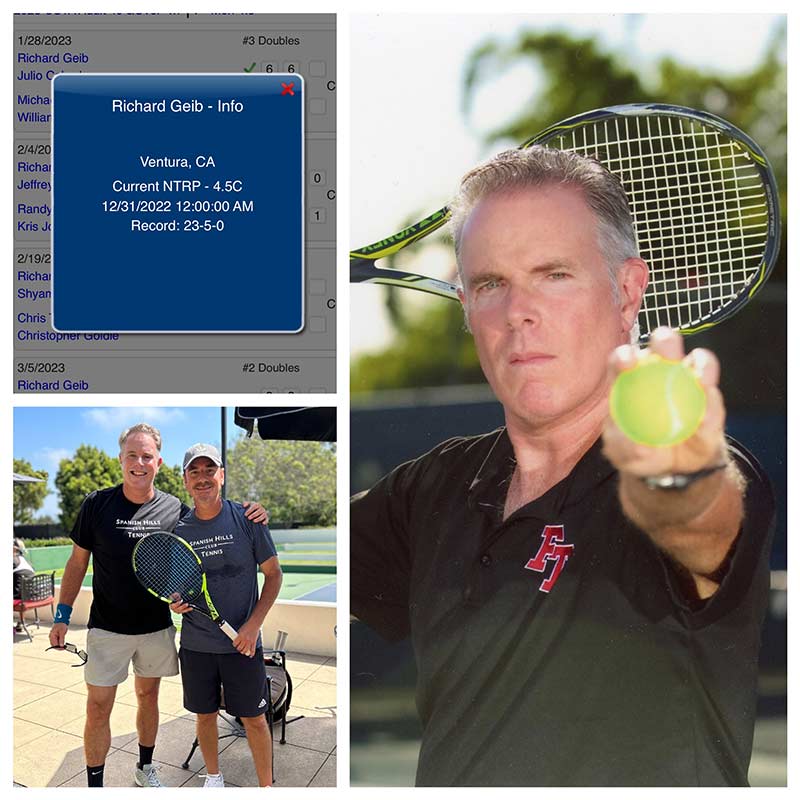

For example, for some 15 months I have been struggling with a knee injury. Athletes feel little strains or aches in muscles and joints all the time, in a temporary pain which a bit of rest will cure; but then there are more serious issues which get worse over time. In this way my knee ached for months as I waited for it to go away, and it didn’t. Match after match I was plagued by pain in my left knee. It became a common sight to see me icing my left knee after a tennis match. “Look, there is Richard with his bag of ice again!” The pain began to bother me not only on the tennis court but also whenever I would walk for longer than 100 yards. I finally saw a doctor who took an X-ray. He then informed me I had beginning (“Stage 1”) arthritis in that knee. It was quite a blow.

My left knee especially hurt at night. I could feel the joint “hot” with inflammation while I laid down to sleep. I bought a special pillow to put beneath my left knee, but sometimes I woke up in pain if I slept in the wrong position. (This is the latest indignity age has brought: I injure some weak point in my body by sleeping in an odd awkward pose!) I knew from experience that everyone has a certain amount of mileage on their joints, and then it is just done. Hip replacements, knee replacements, shoulder replacements – this is what people do when the cartilage is gone and the joint-on-joint pain (ie. arthritis) becomes unbearable. Now it seems to be happening to me at 56-years of age. Or at least it is beginning to happen.

So I had incipient arthritis in my left knee. There was the physical injury. That was one thing. Then there were the emotional effects of that injury. That was an entirely different thing. Beyond months of pain from the knee on and off the tennis court, I also had many many hours of mourning the lifetime effects of a compromised left knee. I felt old. Incapable. This made me feel sad about myself and where my life seemed to be headed. I mourned the body I had had for so many years which had no limitations as it does now; I mourned the fact I had taken so much for granted in my youth, and it was gone. The psychological effects of the arthritis were worse than the pain from the joint itself, and that pain was also real. I sank low in my self-regard (a “has been” with a permanent injury) and those feelings caused me enormous pain for many months, no sense of denying it. I perform my martial arts kata and my knee hurts, and the idea of performing strong kicks with my left leg became unthinkable. “That era of my life seems to be behind me,” I thought. “It is gone.” My spirits sank. I threw myself a pity party, although I confided to almost nobody my full fears. It was too close, too embarrassing. I kept my own council.

At the same time, I sought to process what was happening. If this injury is real, and there are certain limitations I have, what can I still do? Am I “catastrophizing?” Failing to keep it in perspective? Am I still capable on the tennis court and elsewhere, despite the gimpy knee? Or not? Is it really the end of the world? What does this really mean? And how should I feel about it?

Rather than let negative “hot thoughts” run rampant in my mind (ie. my “monkey brain” flinging poop here and there), I sought to form as accurate a view of the situation as possible. Here is what I told myself:

“You are a 5.0 tennis player, Richard. You may play better or worse on any given day, but you earned your tennis ranking. They did not give you this ranking for no reason. Resting your body or taking a bit off will not affect long-term skills. Your left knee is a bit wonky (incipient arthritis), but you are still there. Don’t catastrophize. Listen to your body for messages of pain but also believe in your body. It is still capable. You are winning as much on the court as ever. Your level has not dropped; you have adjusted.

“Remember this: After a year of worry/pain over your knee you played four matches in sectionals in San Diego last August and won all of them with your partners. And you defeated your opponents decisively. Keep the big picture in mind, Richard. Focus less on the negative (ie. struggles with my aging/aching joints) and more on the positive (all the capacities you’ve earned over fifteen years of focused and intense effort). “

That helps. I don’t feel 100% better, but I do feel better. (Maybe 40% better?) If the situation with my knee is not great, it is also not the end of the world. If there are things I can’t do, there are more things I can. Is this not a “coping mechanism”? Shakespeare’s Friar Lawrence might claim that I am using “adversity’s sweet milk, philosophy” to make this bitter brew more palatable. Perhaps. But if so, I will take it. A merely bad drink is better than a horrible one.

And so I sought to manage the changes in my body (knee, but other places, too) as I approached late middle-age. The results were so-so. 60-40? An incontrovertible fact: tennis was less fun, even when winning, when I played in pain. What could I do?

Another area of emotional distress was my job. It is no secret that since the pandemic started back in 2020 and brought with it associated school closures life has been unusually stressful for educators. To be blunt, morale is in the toilet for teachers, and there are shortages of new teachers and older ones fleeing the classroom for better pay and working conditions. I am not immune from this. At times I am on the verge of completely losing faith in the public school system – all the way up from students to teachers to administrators. It is still grappling with the deleterious effects from the COVID-19 disruptions. At times I veer close to not believing in what I am doing. But is that reality? Is the educational system truly failing? Is the way I feel about what is happening in the schools the same as what is actually happening? I am neither very close to retirement, nor that far from it. “Get me out of here!” I say to myself. “This sucks.” I am far from the only teacher saying this.

But I look at my situation more closely, and I see it somewhat differently. In the sober light of day I make a list of pros and cons about my job. I inspect what I wrote down on paper and recalibrate my thinking. Then I tell myself the following:

“Next year you will teach entirely Honors and AP students in the academically strongest public high school in the area where you live. You have almost the best teaching position in the school system. Be grateful. Don’t let school board politics or campus strife drag you down – the former is so stupid and tedious as to deserve next to none of your time or energy, and the latter is as transient as it is inconsequential. Let that stuff slide off your back like water off a duck’s bill.

“You usually thoroughly enjoy the content you are paid to teach, and so you can enjoy your days teaching it while enjoying the give-and-take with the kids as much as possible — all the rest is just noise. ‘Don’t let the shitbirds keep you down.’

“If the education system is in crisis in California, it does not have to be so in your classroom. Close the door, be 100% present to your students, and ignore everything else. Remember this lesson, Richard, and there is no reason you shouldn’t (mostly) enjoy your last few years.

“There is no need to give in to despair, or to feel like a prisoner waiting out the clock until retirement. You are LUCKY to be where you are. And you have earned your current position. Be GRATEFUL. It won’t last forever.“

But this leads me to further questions: In thinking this way, am I completely honest? Is this self-talk about my knee and my career the truth of the matter? Or is it more aspirational thinking towards what I would like the truth to be? Do I seek to sort of brainwash myself? Am I being peed upon and telling myself it is merely raining? Or is this an example of positive thinking helping me to manage change more effectively than I would otherwise? Am I seeking to influence that which can be influenced, and letting the rest alone?

None of the above? All of the above?

Why? How?