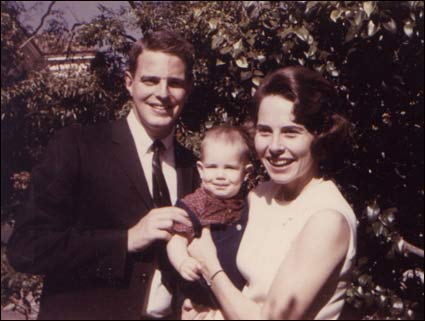

Flowers left on Margaret Mary Geib’s grave on October 31, 2016 by Richard John Geib.

Twenty years, mom.

Twenty years ago today you died. Your body eaten up by cancer like an old fence eaten up by termites.

Twenty years is a long time.

You have missed the weddings of your children and the births of your grandchildren. You were 55 years old when you died in 1996. I was 29 years old. Today I am 49 years old. It won’t be long until I am the same age as when you died. It astounds me to think this.

Neither your early, unlooked for death nor its trauma for our family changed the fact that life goes on. 1996 turned into 1997, and then it was 2000 to 2005 to 2010, and then it was 2016. The hours and weeks and months and then the years they stop for nobody. Your husband, my father, remarried and I have a long-term, positive relationship with my stepmother. Your husband is now 77 years old and in the late-autumn of his life. The world, and our lives, did not stop when you died. Life continued unabated.

And that brings me to the point of this essay: the transience of all the things of this world.

This anniversary of your death, the 20th, has been on my mind for months. I’m not exactly sure why. Is it because “20” is a nice round number? Or because “20 years” signifies a big chunk of time? (I felt similar qualms in my twentieth year of teaching: sounded a bit like a prison sentence to me.)

Yes, twenty years is a lot of time, but sometimes it seems like just yesterday you died. And it seems like twenty more years can be here and gone in a snap of the fingers. Time – so promiscuous, so unrelenting. So flat and so unforgiving. As a child one gives it no thought whatsoever, and a year seemingly takes forever to pass. But time speeds up as one ages and a decade can pass at a trot. Time begins to run out. Suddenly, there is none left.

The logical response to these melancholic reflections is to seize time by the throat – to live fully and vivaciously in the “eternal present.” The impulse is to not squander time. “Carpe diem!” I recognize this. And I do live this way. As a husband, father, son, teacher, friend, and athlete.

But too often one wearies of life as one ages. Less testosterone, less energy, less curiosity…. less most everything. It reminds me of W.B. Yeats and his “Lines written in Dejection” poem. It is one of my favorites, and I used to enjoy tormenting my students who sought in vain to make sense of it.

WHEN have I last looked on

The round green eyes and the long wavering bodies

Of the dark leopards of the moon?

All the wild witches, those most noble ladies,

For all their broom-sticks and their tears,

Their angry tears, are gone.

The holy centaurs of the hills are banished;

I have nothing but the harsh sun;

Heroic mother moon has vanished,

And now that I have come to fifty years

I must endure the timid sun.

Yet when I think about it, to be fair, the sentiment posed in this poem is only partially true. The “dark leopards,” “wild witches,” and “holy centaurs” of hormonally-fueled youth overlook the dark side of “heroic mother moon.” Being young for me (and most) also meant intense emotional distress (anxiety and anger), a lack of money and knowledge of how the world works, and an inability to see the big picture or have life perspective. Aeschylus tells us that with time and pain come “wisdom.” Maybe.

But then there is “enduring the timid sun” at fifty years of age. There is the constant stream of hours, the one leading into the other. And then more hours after that. It is why most older adults find the idea of living forever to be tedious and unwelcome. Like too much bread and not enough butter to cover it. I asked my father last weekend if he would like to be alive in the year 2100, which my daughters have a good chance of reaching. He replied, “I hope to God not!”

The hours. And then more hours. And more hours after that.

Twenty years, beloved mother. Twenty years.