“To find oneself more than a bit lost — while disorienting and even frightening — is far from irremediable.”

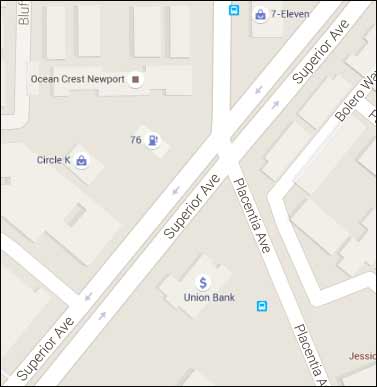

It was sometime in early 1997 as I walking westbound on Superior Avenue in Newport Beach, California. My sister and her then fiancé happened to be driving by, saw me, pulled over, and offered to drive me wherever I was headed.

I was more than happy for the lift. I was badly hungover that morning, and 20 years later I can’t remember where they drove to or where they dropped me off.

Why has this remembrance stuck with me so much for almost an entire week?

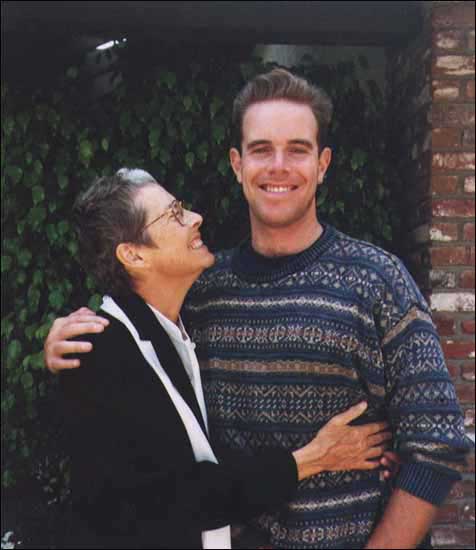

Because I have been thinking about how my mother’s death in 1996 means that this coming October 31, 2016 will make it TWENTY YEARS since my mother died of lung cancer that metastasized to the brain and killed her.

Twenty years!

That morning where mine and my sister’s paths crossed was only a few gray, wintry months after my mother died, and I found myself walking home after a wild night of frenzied bacchanalia with a young lady who had a boyfriend. Her long-term boyfriend was, in fact, away at college. The sport had been as it should be: primitive, urgent, elemental, sharp, no-holds barred. Entirely satisfying. Did I care that she had a boyfriend? Not really. It was not the first night I had spent in her apartment.

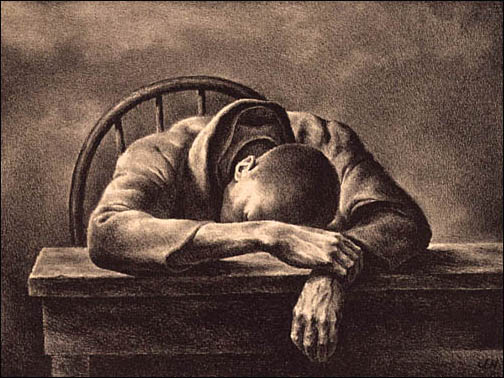

And this brings me to the point of my remembrance nearly 20 years later. I didn’t care about much of anything at all as I walked down Superior Avenue that morning towards home or my car or wherever I was going at the time. Whatever fun the night before had held, the next morning I felt the consequences of having essentially poisoned myself with alcohol. This girl who was cheating on her boyfriend with me. I wanted to go someplace dark and sleep. The sunlight hurt.

I felt so low at the time that to bring myself lower was easy. When you care little about yourself, you tend not to be surprised or outraged when misfortune occurs. One becomes passive. “Who gives a shit?” “Fuck it!” If I had had more respect for myself, if I had been in a better place in my life, then I would not have been walking down Superior Avenue that morning not only hung over but probably still a little drunk.

That moment was almost a low point in my life. And arriving to such a place did not really have much to do with drinking alcohol or the young lady or what had happened in her apartment the night before. It had everything to do with my mother’s death.

I don’t argue that I wouldn’t have been diagnosed as “clinically depressed” at the time. I’m sure I was, although I resist that label. Multiple times my father advised me to go to counseling. “I got counseling both during her illness and after your mother died, and I found it very helpful,” he would admonish me for years afterwards. Others were worried about me, my father claimed. But I never did get counseling. Never talked much about my mother to others.

But I did find my mom taking sick and dying to be a huge blow to my person, as most would. I was profoundly wounded. As I watched my mom in the last stages of withering down, shriveling up, and then dying of brain tumors, it was as if my pores opened up and released cellular memory of being a baby and a little boy who was often in my mother’s arms – feeling her skin on my skin, memories I didn’t know I had until she was dying.

And when the funeral was over, the guests had left, my mother’s clothes given away to charity, then there was a silent aftermath. Life at first glance returned to “normal,” but it was not normal.

The aftermath was sadness, and a sort of numbness which in essence is trauma and resulting depression. It was like the flaming forest after the fire had burned it entire and the land lay silent and ashy.

I moved in with my father after my mom died. It was great to have the healing time hanging around with my dad, but I was living in our childhood house with the ghost of my mother still haunting the place. She had just died. Moreover, I was too old to live comfortably in my childhood home. I was 29 years old.

But to this day I resist the clinical term of “depression” for that time. That label smacks too much of modern psychiatry, the DSM Manual, talk therapy, and SSRI medication. I did not want that. In contrast, I would lay claim to an older concept of “being in mourning.” In my opinion, I was not “depressed” so much as I was “in mourning.” The distinction might seem minor — even immaterial — to some. To me it was important.

As I walked down Superior Avenue on that cheerless morning in March of 1997, I was deeply despondent over my mom’s death. I read today about how in her UC Berkeley commencement address Sheryl Sandberg described living for months in a “deep fog of grief” after her husband suddenly and unexpectedly died. That resonates but does not hit entirely home with me. For me, to be in mourning is to crawl into a protective ball and not care much about the external affairs of the world: bills, jobs, details, what might happen to me, whether willing girls have boyfriends or not, etc. Just floating. Drifting. Going through the motions. Focused inwardly. For me, to be in mourning is metaphorically to assume the fetal position, and then to nurse the bleeding wound until it scabs and then scars over. Then I could engage the world again.

This takes time. Time is the only thing that heals a deep wound. But a scar does not mean the wound ever really goes away. It mostly heals but it leaves a mark. I never thought talk therapy would help or speed up the process. But maybe this is just me.

That is why I was not ready to pursue anything deeper emotionally, even if she had desired it, with that young lady with the long-term boyfriend away at college: I didn’t have the energy. I liked her, but I was unavailable. I was turned inward.

But a year after my mother’s death, I had grown tired of mourning. I had looked my sadness square in the face, sat with it long, and finally was done with it. To be more exact, I was exhausted with being sad. Weary of it. Spent. That meant, in retrospect, that I was ready to move on. A calm returned. I could look strangers in the eye and tell them about how my mother had gotten sick and died without crying, or wanting to cry. I had accepted the changed reality. I got a new job, moved into an apartment, and lived the next epoch of my life.

Over the next several decades I enjoyed success in teaching middle and then high school. Eventually I met a wonderful young woman, married her, started a family, and raised two daughters.

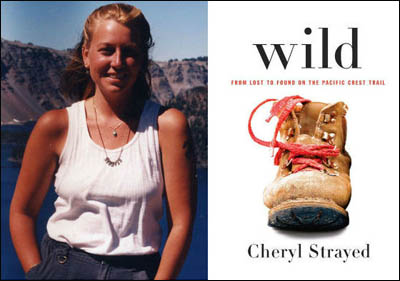

So it was with much interest last summer that I read Cheryl Strayed’s memoir, “Wild.” Strayed also lost her mother to cancer, and she was twenty six at the time while I was twenty nine. Strayed struggled to keep her still semi-formed adult life together as she mourned the loss of her mother, and she engaged in much more reckless and self-destructive behavior than I ever did. The then married Strayed had sex with three different men who were not her husband over five days, showing how little she nurtured her marriage (and herself) at the time; she shot up heroine, hung out in the seedy part of town, and was robbed once at knife-point while in a cloud of opiates. A part of me understands that. (“Who gives a shit?” “Fuck it!”) Strayed suffered for a time, lost in the world. But, like me, she eventually found her footing.

So I guess that is why the image of myself walking down Superior Avenue has stuck so much in my mind lately. I feel for the young man who had come to such a low place, shaking my head in wonder and disbelief. But I would also tell him that he will not always be like this, that patience is all, and that life will turn over another leaf eventually. To find oneself more than a bit lost — while disorienting and even frightening — is far from irremediable. All that needs to happen is to wait and let the world show you something new. It will, eventually. If you don’t do something rash, and maybe fatal. Patience.

And so I’ve taken the trouble of writing down this remembrance for other nascent adults to read who might find themselves in a similar predicament. As Saint Frances de Sales claimed: “Have patience with all things but first with yourself. Never confuse your mistakes with your value as a human being. You are perfectly valuable, creative, worthwhile person simply because you exist. And no amount of triumphs or tribulations can ever change that.” Amen.

Postcript: There were even improvements in my life that came from my mother dying decades before she should have, although I would very much hesitate to call her dying and death “positive” for me. In my early twenties I was prone to a particular tone of cynicism and unhappiness that came from reading too much Nietzsche and Schopenhauer. I could be dour. Negative. Not to people individually, but to the world in general and towards the possibilities of myself being happy in it. Sophomoric.

That changed after the experience of watching my mother die. After I emerged from that funk, I have not been “depressed” since. It re-set my emotional balance forever after, for the better. I am content with life on a daily basis, as long as nobody in my family or close acquaintance is dying of cancer. This is an improvement.

Post-Postcript: I learned it in my bones, through watching my own mom die with my eyes, that this would happen to me, too. Might as well enjoy today before that day comes for me, also — or so I concluded. (Twenty, thirty, forty years more? It would not be so long. Maybe at the moment when I come to die, it will have seemed like only a few moments ago that my mom died, too.) So I have lived. This is wisdom, or some approximation of it.

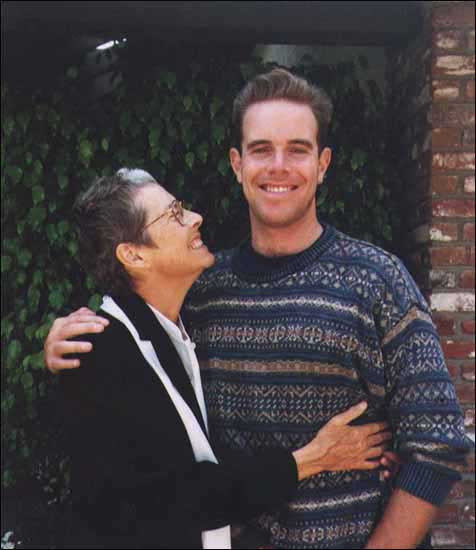

My mother and myself, as she underwent chemotherapy for lung cancer in 1996.