There is the concept of what some job might – or should – be. There is the noble idea of a vocation – or a calling to do some job professionally and help make the world a better place. Through your life’s work you can contribute to the collective, rather than merely taking away from it. A person can earn money and make a difference in the lives of others at the same time. Your job can be the ultimate expression of your reason for being alive – the pinnace of your existence – your “life’s work.”

I fully understand plenty of people just take a job for the money, and they have little sense of a “calling” to do a particular job. They work at the neighborhood grocery store, or they change oil and fill up car tires; they do a job for the money, and that is about it. Or they don’t ever really engage in the workplace at all. I am amazed how many people I ask if they like their job and they respond, “It’s OK.” What becomes clear is that they do a job without thinking too much about whether they like it or not. It is a job. They do it, they get paid. Not much more thought than that goes into it. They expect little from work and don’t give it much. So they are not disappointed when work gives them little in return. “It’s just a job.” Fair enough.

But work can be different for those who have a “calling” to perform some role in society. They may spend years training to be qualified to do it, and then they may be energized and engaged at a high level. The job requires much, but it also gives much. Many Americans are almost married to their jobs, and it is the most important thing in their life. But almost always such people discover sooner or later that a job is still only a job, and it can break your heart – especially if you have unrealistically high expectations.

Take a police officer, for example. A cop might feel called to “protect the innocent” and hold thugs and other lawbreakers to account. He or she might swell with pride in graduating from the police academy; they are ready to get out there and “make a difference” and “do some good.” But after a few years they will discover they are essentially arbiters being endlessly called to one bitter disagreement after another, trying to calm the aggrieved parties down and “keep the peace.” Bitterly feuding spouses in “domestic disturbances,” angry drivers in “road rage incidents,” homeless drug addicts beefing with each other in the gutter, and angry customers screaming at store employees – all day long you are dealing with enraged people in angry disputes. Often both parties are at fault to one degree or another.

And then over and over again you respond to a “call for service” and arrive only after a violent incident has taken place – a beating, a stabbing, a shooting – and you can’t do anything other than write up yet another police report on what happened, sometimes over the body of the deceased. You are more a chronicler of violence after the fact, than a preventer of such violence. Then with the law and department regulations there is only so much you can do with thugs and lawbreakers, and only so much protection you can offer to your fellow citizens. Are you protecting the populace? Can you be everywhere all the time? Is your community “safe”? A veteran cop might reflect on whether he/she can protect the innocent and come to the following answer: “Maybe. Sometimes. It depends. It’s complicated.” And he/she might continue to answer: “If you really want to be safe you also want to get a dog for protection and maybe a gun, too. I would not rely only on the police. And I’m saying that as the police.” The cops can help sometimes – if they’re around, if department regulations permit it, if the law allows it – but there are other times when they can’t, especially in high crime areas, in the world as it is. Any veteran cop most likely has serious reservations about the career path they chose.

I had a wonderful student some fifteen years ago who chose to attend the United States Military Academy. He was on fire to walk in the footsteps of Ulysses S. Grant, Dwight Eisenhower, and H. Norman Schwarzkopf. In his imagination rang the hallowed words of “duty, honor, and country.” Even as I wrote him a glowing letter of recommendation to West Point, I tried to caution him in his idealistic ardor. “There is aspiring to serve one’s country at West Point – the ideal. Then there is the stupid infighting politics and endless bureaucratic paperwork – the reality of actually being an officer in the army.” The two are not the same. The one might even be the enemy of the other. Caveat emptor!

Or how about being a doctor? A young adult enters medical school wanting to live up to the Hippocratic Oath of working to save lives while “doing no harm.” Doctors spend years acquiring specialized knowledge which could mean the difference between life and death for patients. But working doctors spend gobs of time dealing with insurance companies, malpractice lawyers, and a litany of other bureaucratic concerns. And then so many patients are their own worst enemies, and they will not listen to or heed medical advice; they leave the doctor’s office after a visit, and come back later worse than before. Patients are often their own worst enemies, and doctors can do nothing. Furthermore, patients tragically get sick and die all the time, despite the best ministrations of even the best physicians. Does a doctor spend their best hours and energies helping patients to get better? “Maybe. Sometimes. It is complicated. It depends.” There is the theory of going into medicine to be a doctor. Then there is the reality. The two are often different. The spark of idealism might still live on in the heart of the veteran doctor, but it has been battered and almost smothered by reality. Is this a skeptical wisdom brought by long and hard experience? Insiders know the ugly realities of a business when they see it from the inside.

Then there are teachers, like me. We love the subjects we teach and wish to pass on that love of learning to our students. But working in schools, especially public schools in America, presents a whole host of concerns. How many students care not a jot about learning anything in school? They just go there to socialize with their friends and/or make trouble? How often do conditions in the home of students themselves – poverty, neglect, incuriosity, abuse – result in subpar academic performance? (Conditions over which teachers have no control.) How many schools in America are underfunded, teachers underpaid, conditions miserable, and learning less than ideal? The directives from school district administrators are often laughable and ever-changing, and the resources for meaningful professional growth for teachers are either miniscule or non-existent. In your classroom as a teacher, you are pretty much all alone with your students. You don’t get much support. In fact, most teachers get next to no support.

Teachers leave the profession in droves not particularly because they dislike teaching, but because the job is almost impossible to do well for reasons beyond their control. I don’t blame them. I have not met many teachers who want their own children to follow in their footsteps: that is a telling detail. Whatever love and desire for academic excellence you had in your heart as a beginning teacher, it has probably been mugged by reality after a few years in the trenches of your average American public school. A parent might ask, Does the neighborhood school where I live offer quality-control so that all students achieve and learn? The veteran teacher responds: “Maybe. It’s complicated. It depends.” She might continue on: “I would pay close attention to the teacher your school assigns to your child, and I would be ready to teach my child at home to fill in the gaps the school fails to cover. Be advised!” Parents are the first and foremost teachers of any child, and a wise parent would be careful not to relegate anything of crucial importance to someone else, especially to a public school with union-protected teachers who can’t be fired. “Quality control, my ass!”

Does all this sound like disillusioned crankiness from someone approaching retirement? Is it harsh reality taking a dump on airy idealism? Age and experience kicking dirt in the face of hope and youth?

Maybe.

Do I have any idealism left in my 29th year of teaching?

Yes. I have the same idealism today in looking into the eyes of my students as I had in the beginning. I want to do the best job I can for them. The difference? I have so much more experience of knowing why that probably won’t happen for many. As for looking for wisdom or guidance from assistant superintendents or other education bigwigs? I expect nothing. Or I expect worse than nothing: actions and policies which will get in my way as a classroom teacher. When I was a new teacher overjoyed just to have a job, I innocently thought the big bosses in education knew what they were doing. I cautiously respected their authority. Now I know better. Yes, I have (to some extent) become that cranky older teacher who kind of shocked me with their cynicism when I was a new teacher. I would do a lot for my students. I am not sure I would lift my little finger to help my school district. This is what experience has taught me.

And my opinions on the world of work get worse from there, unfortunately.

People occasionally ask me, “What other job might I want to do part-time after you retire from teaching?” My answer: none. At 56-years of age I look around and most jobs out there look undesirable or worse. Work as an accountant or bookkeeper? Oh my God no. Work in sales or marketing? My skin crawls at the thought. Sit at a desk and stare at some screen all day long in an Information Technology job? No thank you, I would prefer bamboo slits to be stuck into my fingernails. A position in Human Resources? Banish the thought! There are so many jobs from which I recoil in horror. I would do so horribly in them. I realize this so much better now than I would have three decades ago.

I think the more important point is that I have few ambitions left in terms of the workplace. A job is almost always a job. If it wasn’t at least usually laborious and tedious, they wouldn’t call it “work.” And I don’t want money or prestige or “a challenge” at work. Not anymore. At this point of my life I want to do something different from what I’ve done over the past three decades. I occasionally come across some guy in his thirties full of piss and vigor with a strong desire to leave his mark on the world through entrepreneurial activity or political activism or whatever; his hair is on fire, and he is animated and validated by success (or the prospect of success) at work. I am on the opposite end of the spectrum. I have had a measure of success at work. Now I want peace and calm and independence. I want to exercise, read, and think. I don’t want to “work.” God knows I don’t want pressure and stress. I’m done coming home at night frazzled and overwhelmed. I want equanimity. I want freedom.

I used to identify solidly as a classroom teacher, and it was close to the center of my conception of the self; I had something to prove to the world through success on the job. I was young and ambitious. Now teaching is just one of many things I do, and I have little left to prove; I repeat my mantra of “ego is the enemy,” and I do so more every year. I want to reduce my profile and like Douglas MacArthur’s old soldier “just fade away.” I’m done, more or less. I’m ready to retire. A non-teacher friend once asked me if I cared about my “legacy” in the school system. I told him teaching was not like other jobs where that was important: there is a binary union-management dialectic at play. Instead of a more “professional” and responsive work culture as found in better run organizations like law firms, you have a situation in the public schools where both sides dislike, distrust, and undermine each other. So as a result your “reputation” is almost irrelevant with the ever-changing lineup of bosses. It is attached to short-term political considerations which may or may not have anything to do with your real quality as a teacher. Long experience in the educational system has led me to the point where if some administrator says something is good, I suspect it probably is bad – and vice versa. It has gotten to that point. School administrators are not really “educators,” in my experience. They are more politicians. This is not always true. But it is almost always true. So move forward on this understanding, dear reader. And beginning teachers beware!

A critic might ask, “As a relatively young man you are done with the world of work? There are no jobs that interest you?”

I would not go that far. I think I might want to read to elementary school kids twice a week (for free). After lunch on Tuesday and Thursdays I could read Where the Red Fern Grows to 10-year olds after lunch while their teacher gets a break to grade papers. I would enjoy that. Or maybe I could do some volunteer AP US History tutoring at the school-wide level? Or maybe serve as a victims advocate or grief counselor for the DA’s office? Something limited like that. Maybe work for a nonprofit serving talented youth with few resources. Something part time. Interesting and rewarding. Dealing with people, not spreadsheets. No sitting endlessly at a desk staring at complicated information on a screen, God no. That is almost the plague of American professional life presaging ill health through an overly sedentary lifestyle begetting obesity and back problems, as is captured in the expression, “Sitting all day in a chair is the new smoking.”

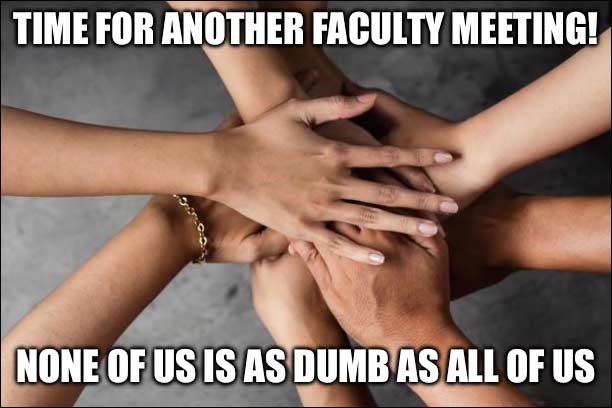

I certainly won’t stand to have my time wasted in worthless meetings anymore. I heartily agree with columnist George Will when he claimed that “football combines two of the worst things in American life. It is violence punctuated by committee meetings.” They are almost always horrible, these workplace meetings. Here are some memes I created while sitting there frustrated during inane staff meetings, and which I then sent by text message to a teacher-buddy sitting nearby:

Look at these images! Talk about deriving a “silver lining” from a miserable situation. I enjoyed making those memes. After many long years of sitting through painful work meetings, I found a way to make the most of them: I create memes. This keeps the dying embers of creativity and innovation burning. That is not nothing.

But overall I have lost faith and am done. The reality overwhelms the theory. Let someone younger than me try and salvage the mess. Good luck! You’ll need it.

The old leaves off so that the young might take over. Such is the natural order of things. Maybe the next generation will have more success. We shall see; I have my doubts. I have good reasons for those doubts.