I recently finished Gerald Marzorati’s new book, “Late to the Ball: Age. Learn. Fight. Love. Play Tennis. Win.” I enjoyed the tennis references, of course, but what I most enjoyed were the meditations about retirement and aging, friendship and connection — and on learning to do anything new and grow in the process. For Marzorati, this happens through taking up tennis in retirement at the improbable age of 60. But it could apply equally to someone learning to play the piano, cook Italian food, ballroom dance, or speak French.

I have seen it all this week as my two young daughters just started learning to rollerblade, wobbling around awkwardly on wheels like baby deer taking their first tentative steps. It takes them way out of their comfort zone.

As a teacher myself, I often reflect on how teachers ought always to be learning something new. This would help them to sympathize with their students who struggle to gain competency in the basic skills which the teachers themselves have long since mastered. We forget how hard it is to get started; we lose sight of how proud students can feel (or should feel) in the minor victories involved in learning to take baby steps. It is often said that the best math teachers are those who struggled to learn math themselves, as they are much more in tune with the difficult process of acquiring mastery than those math whizzes who learned it effortlessly.

Gerald Marzorati could have eased into retirement by settling into a sedentary life, as many do. This is, I suspect, the first step towards withdrawing from the world and preparing to die. In contrast, Marzorati eagerly takes up a difficult sport and spends many thousands of dollars and much of his time and energy in his new pursuit, tennis. He throws himself into the endeavor with energies more often seen in the young. How impressive! How unusual.

It seemed obvious to me, as a person who has played tennis longer than has Marzorati, that he was trying to do too much too quickly. Spend less money on tennis instruction; give yourself more time to grow into the sport; try less hard, allow the process to happen more naturally. Marzorati might reply that at sixty years of age he cannot afford such time. Maybe.

But my take way from this book are the insights Marzorati gains in terms of positive attitude and mental outlook. In particular, I was struck by the words of Bob Litwin, a veteran player/coach who councils Marzorati on his game. As Marzorati grows angry in making errors on the court, Litwin speaks the following to him across the net:

“Where is all that negativity coming from, Gerry. Do you know you grimace, just a little, but you grimace every time you miss?

“Why? You are a sixty-year-old man who had the good fortune to be out on a tennis court on a sunny morning. Look at us!”

He turned to the chain link fence that ran along the side of the court. “I want you to imagine the people who love you are here, watching you, supporting you. Me, I always imagine my father. Others, too. Who are your angels?”

This struck me to the core. I almost started to cry upon reading it.

Tennis has been described as boxing at eighty feet, and the gladiatorial aspect of two people going at it until one submits and loses to the other can contribute to a powerful psychic tension. Looking across the net at your opponent, it can get personal. One player will win, the other will lose. In singles tennis you cannot look to teammates for help in the heat of the battle. It is all on you. Maybe more so than in most sports, the mental game is crucial. And we amateurs perhaps cannot learn overly much from the strokes and movement of professional tennis players whose age and life circumstances are so dissimilar to our own, but we can definitely learn from the way they control theirs emotions and manage stress. Their attitude.

of the battle. It is all on you. Maybe more so than in most sports, the mental game is crucial. And we amateurs perhaps cannot learn overly much from the strokes and movement of professional tennis players whose age and life circumstances are so dissimilar to our own, but we can definitely learn from the way they control theirs emotions and manage stress. Their attitude.

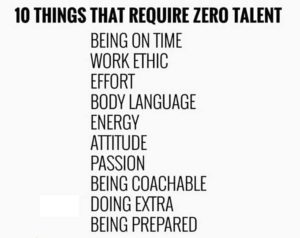

Especially as we age and the body struggles to do what it once did, we can still firmly control out attitude in sports. So many factors are out of our control, more or less, but our attitude is not one of them. I tell my daughter all the time that it is not so important necessarily if she should win or lose in tennis. It is to be always focused on continually improving as a player and growing as a competitor, and if she focuses on that than the victories will come. I think all superior athletes are focused more on the process, less on the outcome. Desiring to win or hating to lose can have a corrosive effect on performance, getting in the way of being in the moment and focusing on the point being played – on playing the highest quality tennis one can at that moment. To focus on improving, without the ego and vanity mucking things up. They say great champions such as Roger Federer love the process of growing as athletes and improving as competitors as much or more than the actual winning.

I tell my daughter this, and it seems I tell it to her often. She struggles to remember. But I struggle to remember it myself. Teacher, teach thyself!

So who are your “angels,” Richard? Who is watching and rooting for you in the heat of battle on the court?

And those superior tennis players who beat you, Richard, and are just better than you are – they are not your humiliators, “beating you down.” They are your teachers, showing you how to get better. And you should thank them. They can make you more, not less.

This is important stuff!

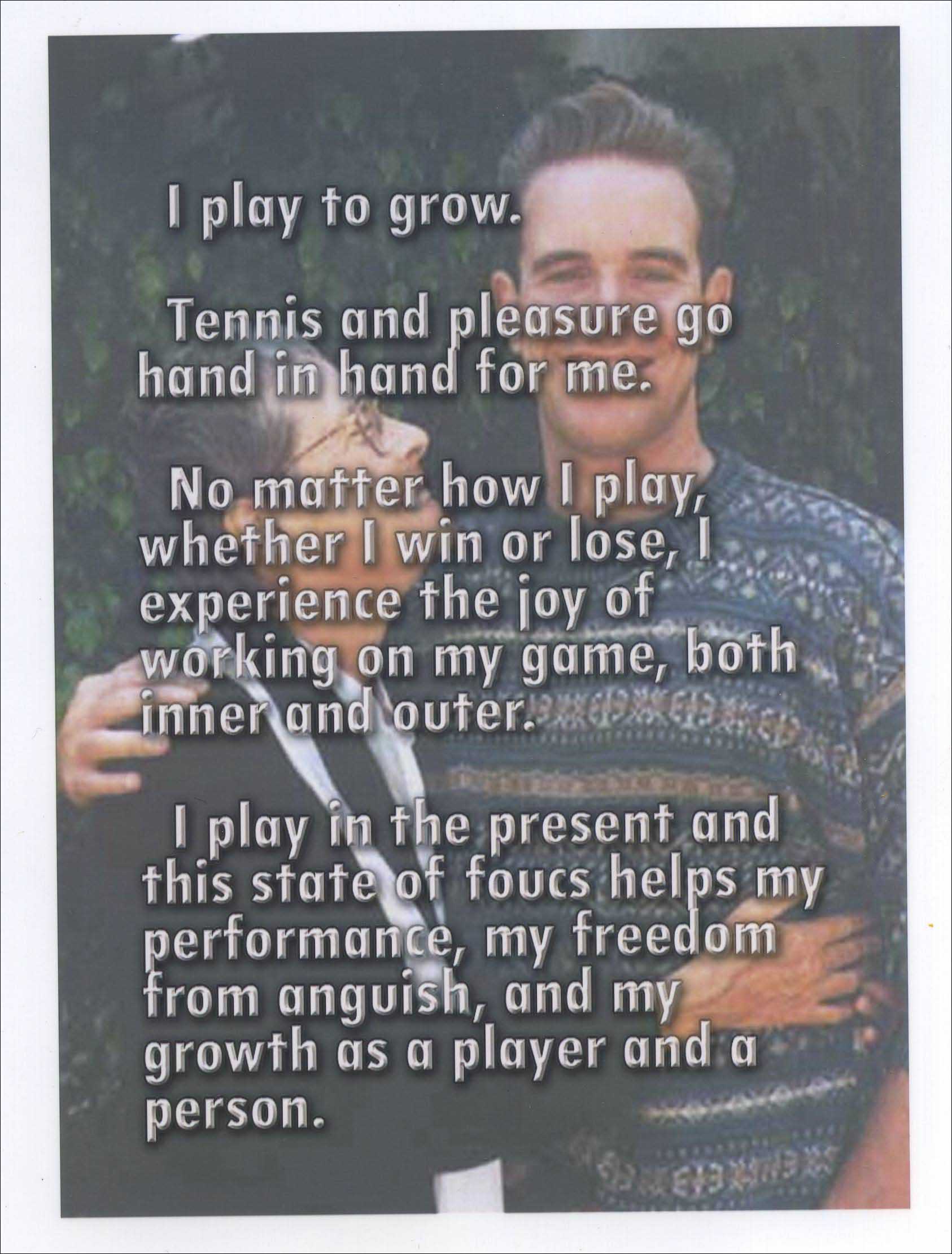

Bob Litwik told Marzorati to print out the following and use it as a sort of tennis prayer:

I play to grow.

Tennis and pleasure go hand in hand for me.

No matter how I play, whether I win or lose, I experience the joy of working on my game, both inner and outer.

I play in the present and this state of focus helps my performance, my freedom from anguish, and my growth as a player and a person.

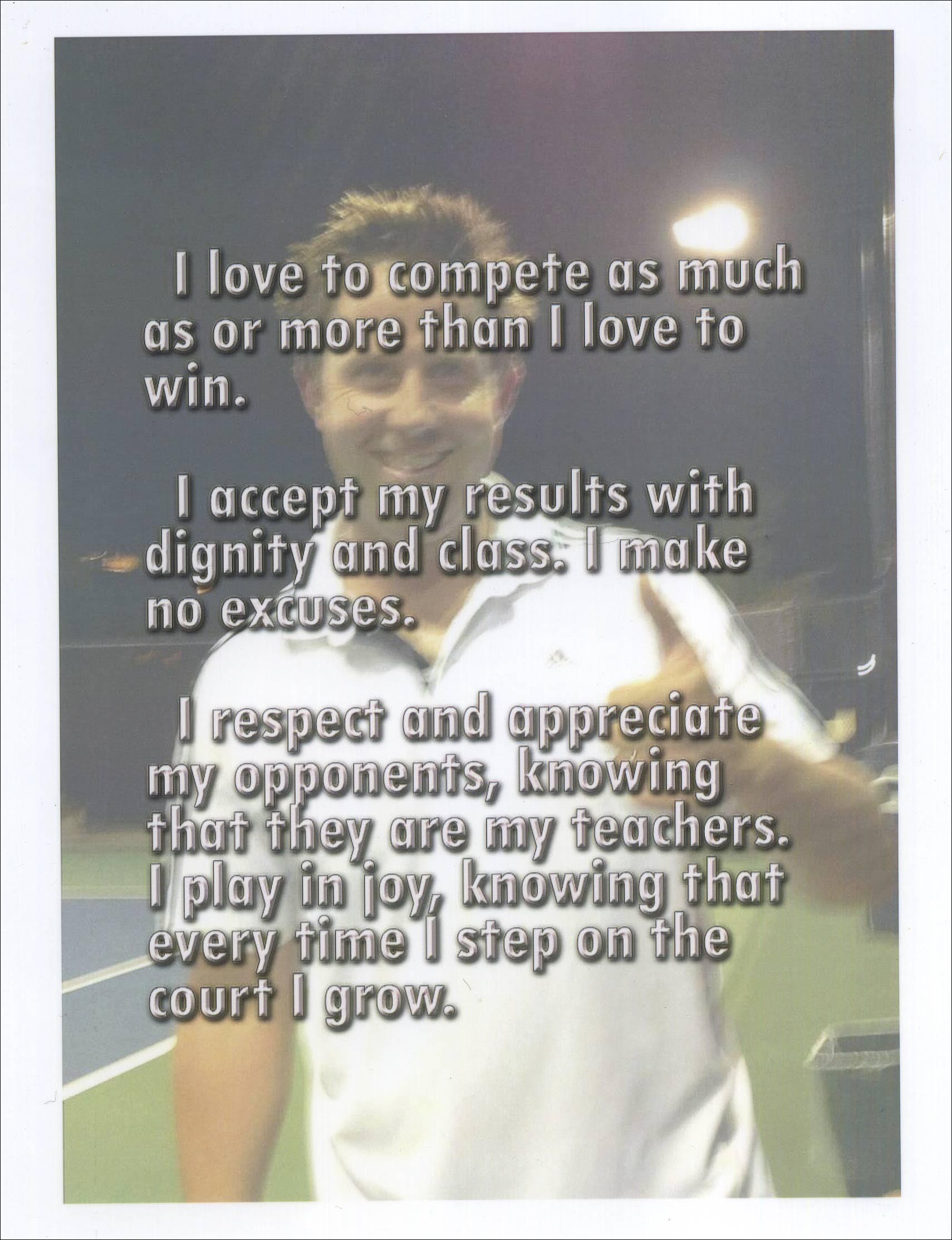

I love to compete as much as or more than I love to win.

I accept my results with dignity and class. I make no excuses.

I respect and appreciate my opponents, knowing that they are my teachers. I play in joy, knowing that every time I step on the court I grow.

This is huge. Often our attitude becomes a creature of habit in tennis, as we lazily allow bad habits to sneak into our game. An expletive uttered quietly as our first serve sails long, or negative body language when an important point goes to our opponent. Such negativity is not helpful. It serves not.

The better angels of your nature do not approve, Richard. Those that love you smile not on such acts. You should know better.

So I printed out Litwik’s words over the faces of my guardian angels, and they sit in my tennis bag at the edge of the court while I play. I used Photoshop to superimpose the words over the faces of my guardian angels, and then placed them back-to-back and laminated the photos together and put them in a little used pouch in my tennis bag. They remind me to live up to the best of what sport is capable of – of what I am capable of. I do not forget this. These guardian angels are there whenever I play tennis.

Especially, Chris, who loved tennis, too, and was my doubles partner before his death. I don’t think I have known a person who loved to compete himself (and coach others) more than did Chris Prewitt. He would have loved the words that surround him as I sweat and struggle to be the best tennis player (and human being) I can be, on and off the court. And my mother, too, who was an excellent tennis player.

They understand. They are watching. They are with me. “Time to play a third and deciding set,” I tell myself. Time to perform under pressure.

Thank you, Gerald Marzorati, for sharing your learning experiences and giving us a glimpse into your tennis mind. Henry David Thoreau once wrote, “How many a man has dated a new era in his life from the reading of a book! The book exists for us, perchance, which will explain our miracles and reveal new ones.” This assertion is made true by your book.