Today in class I finished showing the 1980 movie “The Elephant Man” to my students. We are reading “Catcher in the Rye” and focusing on how alienated, troubled persons do or don’t get the help they need by finding those that can help them, and then making allies of them and getting the help they need. They communicate, they connect, and they get their needs taken care of. Or they don’t. John Merrick, the “Elephant Man,” helps those who would help him. In contrast, Holden Caulfield in “Catcher” fails to communicate clearly to others what he needs, and so nobody gives it to him. It is a case of miscommunication on behalf of virtually everyone — and so believable in adolescence, and everywhere else for that matter.

And so when John Merrick lies straight back in bed to go to sleep at the end — knowing he will die if he does so — and the movie ends, I was crying while asking a few final questions of my ninth grade students. The students were sad, too, I think. But they were not crying. I think they were looking at me and beholding the strange sight of a teacher — a full grown man — crying. I think they did not know quite what to think. Were they embarrassed for me? They were only fourteen years old.

The same happened a few months ago when I was talking at length with high school juniors about the grisly reality of Civil War hospitals and the primitive battlefield medicine practiced there — with extended readings from Walt Whitman’s hospital days and some Ken Burns clips. We looked at the astonishing casualty numbers from that war, and then I read Sullivan Ballou’s letter to his wife on the eve of his death on the battlefield. I choked up at the end and cried a bit while reading. Nobody else was crying. They were sort of watching me cry, curious.

“Why aren’t you crying?” I thought to myself. “Do you really appreciate what we just read? The horror of it all?”

Maybe I am being too sentimental in a maudlin sort of way. Am I overreacting? Mawkish tears? Am I that “bleeding heart teacher” who squirts treacly tears too often while students roll their eyes? I don’t think so; consider the context. Maybe I cry and my students don’t because I appreciate better what happened. I have studied it longer. Maybe.

I remember when I taught a Bioethics class and we looked at euthanasia and “end of life issues.” We watched “The Suicide Tourist” and watched ALS victim Craig Ewert commit suicide on camera. His final words in the film are:

“Someone once said, ‘He is not completely gone as long as one person remembers his name.’ My love and best wishes to all of you.”

Wow! Or watch the protagonist in Margaret Edson’s magisterial “Wit” get sick and then sicker from cancer, look her mortality in the face, and die in terror and alone — her body wracked by pain and ruined by tumors and chemotherapy.

I think there were one or two students who were crying with me towards the end. I couldn’t help crying, and I figure if watching that does not make you cry then nothing will.

Or the long unit I taught on on “transhumanism” — the merging of mechanical and organic matter — and technology holds the promise of immortality and the blurring of what it means to be “human.” We would watch Steven Spielberg’s strangely uneven but powerful movie “A.I.” — exceedingly difficult to watch. I fight the tears towards the end and lose.

The question I always wanted to ask my students is the following: Why are you not crying with me? Do you truly understand what you just saw? What is wrong with you?

What is it with young people?

Yet I remember when my parents took me to see “The Elephant Man” in 1980. I was not crying as we walked out of the theater. I remember the film won awards at the time, but I did not see why. My mind could appreciate the film, but my heart did not quite get it. That changed when I got older, obviously.

When I was a high school freshman in 1981 I saw “Chariots of Fire” with my dad. He very much wanted me to see it, but at fourteen years of age I found the movie ponderous and a bit boring. My father was severely disappointed at my reaction. “Don’t you get it?!?” he asked me in exasperation. By the age of 30 I came to agree with my father: that movie is a masterpiece. Why could I not see that when I was 14? Why was I not crying when I first saw “The Elephant Man” when I was 13? How did I change as I got older? Was it because I had the experience necessary to appreciate the tragedy of our human experience? Because I had seen with my own eyes by then death and disaster while working for years in a trauma center, and therefore could feel it in my bones when I came across it? Was I just immature in my youth? Unable to get my mind fully around it? Not old enough truly to “get it”? Maybe it is that simple.

My daughters will burst into tears when a playdate is cancelled, or if they can’t watch a video because of misbehavior. Their tears are directed at personal events close at hand. They can’t yet see the big picture. They have difficulty seeing heartbreak and profound suffering as an inescapable fact of life. They struggle to understand and appreciate tragedy when it happens to strangers.

I was driving while listening to the radio last Sunday with my nine year old daughter Elizabeth when Cavatina by Stanley Myers played over the classical station, and the music reminded me (as that song does) of my friend Chris Prewitt’s death. I pulled off the road and started crying. Elizabeth was surprised and grew alarmed, and after a bit she hugged me and started crying a little, too. But she was crying because I was crying; she was not crying at the remembrance and contemplation of horror and ruin — of what used to be, and no longer is. She was not crying because she remembered a husband and father ripped from his wife and daughter in a blur. I was.

When children cry, they do so loudly as in a tantrum. When adults cry, they do it quietly and with resignation. It is different. Adults cry because they know the world is as it is.

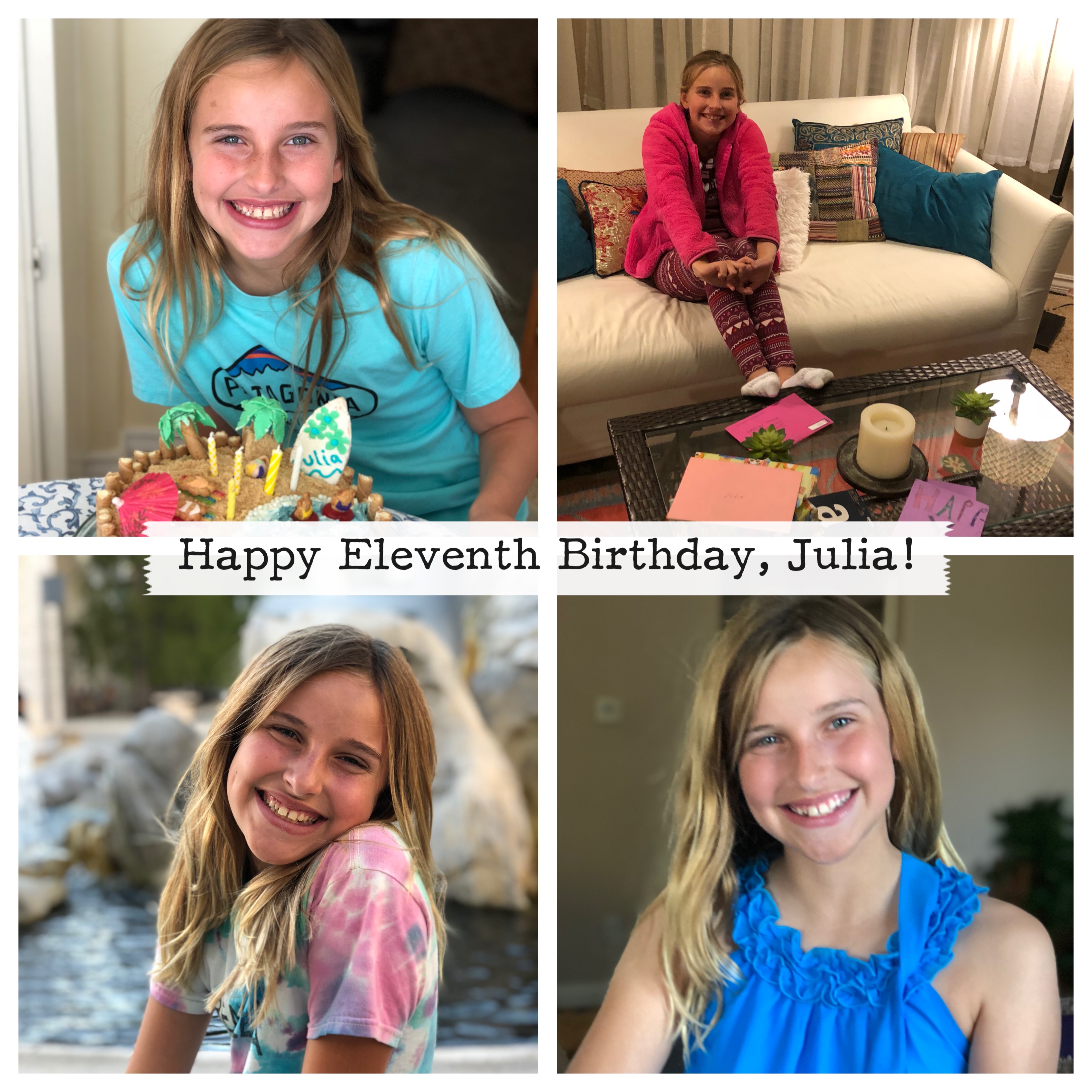

Yet eleven year old Julia has cried for a day or two at the tragic end of a book. Sobbing and sobbing — “That was the worst ending ever!” It was the saddest ending ever, is what she wanted to say. She was inconsolable. She got it.

I remember way back in 2005 one particularly precocious English student who cried when we read “Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking” aloud in class. She was the only student in many years of reading that poem to do so — and she later became an English teacher, perhaps not surprisingly.

Maybe that is what makes an English teacher effective — their ability to read a Keats sonnet about death and be ready to cry, as one should. But I have seen English teachers who run their classes more like boot camp drill instructors.

I don’t know.

But I do know that Julia and I will memorize the 23rd Psalm together. After that we will watch “The Elephant Man” together and cry our eyes out, as one should. I know Julia will cry her eyes out. (I bought the movie on iTunes a year ago in anticipation and the time is almost right.) Then after we watch the movie I will tell her, as I tell myself, that when all seems lost and there is no hope, when the ship goes down and the water is rising — I will recite, like John Merrick, the 23rd Psalm. I will find strength and power in those words. I will keep my head above the water. I will urge her to do the same all through her life. I doubt she will forget the lesson. I know I won’t. It is a tool to help ward off despair. To find courage in the darkness. To appreciate the beauty of what it means to be human in the most profound sadness in life as much as in triumph, bliss, and ecstasy.

“Doctor, heal thyself!”

Yes, there it is, Julia and Elizabeth, my most important students. There they are, the recipients of my best — my most personal — moments of teaching. The fact is that all parents teach their children from their own examples and how we live our lives. We live our lesson plans. We teach what we know.

P.S. I have at times written about my frustration at being a teacher. How I look forward to retirement. But how can one crunch numbers and sell stuff in the business world when one can read “Catcher in the Rye,” or watch “The Elephant Man” or “Wit” or read/watch “Romeo and Juliet” or learn about the Civil War? When one can peruse the amazing emotional range of what it means to be a human? Teaching the humanities is…. INTERESTING. I never found dealing with money to be very interesting. It might be nice to buy something, but it does not engage much my imagination.

P.P.S. So much respect for David Lynch who directed “The Elephant Man” and J.D. Salinger who penned “Catcher in the Rye.” I marvel at the artistic creations they wrought. I stand more than a bit in awe of them. Oh, the divinity in man!

Ars longa, vita brevis!

THE STOLEN CHILD

William Butler Yeats

Where dips the rocky highland

Of Sleuth Wood in the lake,

There lies a leafy island

Where flapping herons wake

The drowsy water rats;

There we’ve hid our faery vats,

Full of berrys

And of reddest stolen cherries.

Come away, O human child!

To the waters and the wild

With a faery, hand in hand,

For the world’s more full of weeping than you can understand.

Where the wave of moonlight glosses

The dim gray sands with light,

Far off by furthest Rosses

We foot it all the night,

Weaving olden dances

Mingling hands and mingling glances

Till the moon has taken flight;

To and fro we leap

And chase the frothy bubbles,

While the world is full of troubles

And anxious in its sleep.

Come away, O human child!

To the waters and the wild

With a faery, hand in hand,

For the world’s more full of weeping than you can understand.

Where the wandering water gushes

From the hills above Glen-Car,

In pools among the rushes

That scarce could bathe a star,

We seek for slumbering trout

And whispering in their ears

Give them unquiet dreams;

Leaning softly out

From ferns that drop their tears

Over the young streams.

Come away, O human child!

To the waters and the wild

With a faery, hand in hand,

For the world’s more full of weeping than you can understand.

Away with us he’s going,

The solemn-eyed:

He’ll hear no more the lowing

Of the calves on the warm hillside

Or the kettle on the hob

Sing peace into his breast,

Or see the brown mice bob

Round and round the oatmeal chest.

For he comes, the human child,

To the waters and the wild

With a faery, hand in hand,

For the world’s more full of weeping than he can understand.

“For the world’s more full of weeping than you can understand.”