Sometimes I think back to when my oldest daughter was in fifth-grade and I would pick her up from the bus stop at 3:10 pm. She would exit the school bus and walk over to me exhausted and in tears. She arrived to me in quite a state. I realized her friendships took a lot of work, even at 10-years old, and the trials and tribulations of life on the elementary school yard were significant.

But I would get her a snack, give her half an hour to decompress, and my daughter would be good for the rest of the day.

I still think about this often.

My daughter was excellent at making friends, managing her friendships, and earning good grades at school. Nevertheless, it was still hard. The twists and turns of her girlhood friendships could be exhausting. I never knew how tiring girl friendships could be until I saw them vicariously through my daughters!

It made me feel a bit helpless as a dad. I recognized that these battles my daughter would have to fight on her own. I was not going to get involved in childhood friendship spats unless I really had to, although my wife was more ready to intervene. “Let her fight her own battles, unless the situation becomes extreme,” I argued. “We will only muddle things and make it worse if we get involved. She will figure it out.”

I still believe that. And the older our daughters get, the more I believe it.

In contrast, I come across many parents – almost exclusively mothers – who are constantly in “their child’s business.” They are advocating for their child aggressively in many ways: in friendships, school, sports, etc. They are sometimes decried as “helicopter parents,” or “snowplow moms” – clearing difficulties out of the way for their precious little babies – too much so, in my view. This makes it difficult for young people to advocate for themselves, in my opinion, or to problem-solve and gain valuable coping skills later on. I still remember reading about the Stanford dean dealing with parents emailing them from home to deal with their adult children away at university. It is hard for me to conceive that parents would be emailing their children’s college professors for them… but it happens nowadays.

But the other side of the coin is a reality, too: there are other parents who pay next to no attention to their kids! I see this all the time as a teacher. But I also come across tenacious “tiger moms,” too.

As a parent myself, I try to tread the middle ground between ignoring my children and obsessing over them. Where is Aristotle’s Golden Mean? Being a parent can be so frustrating in large part become one is never sure if one is doing the right thing. A problem confronts my child. Should I act forcefully and intervene? Or stand back and let my child deal with it? Should I do this, or the other thing? It is rarely clear what the right course of action is. You struggle to do what is best as a parent, but you are rarely sure what that might be.

I remember when my oldest daughter was in seventh grade. She had a science teacher – let’s call her “Mrs. B” – who was infamous for being a horrible teacher. My daughter had had mostly excellent teachers before and was a straight A student. “Let her work her way through a less than ideal situation with Mrs. B, and she can learn to adapt and make the best of it. Sometimes in life you just have a bad teacher,” I thought to myself. I was not going to be that stereotypical pain-in-the-ass parent who demands this or that from school administrators. We would work with what the universe gave us in Mrs. B. But that seventh grade science class was so negative, and the teacher so toxic, that my daughter’s spirits sunk lower month after month; it seemed like Mrs. B exerted a black hole-like influence on my daughter (and other students), pulling her down and down inexorably into greater and deeper levels of darkness and despair. My daughter made it through, regardless. But when I asked her years later if I should have spoken up and got her transferred out of Mrs. B’s class, my daughter simply said, “Yes.” My daughter had a friend with a very pushy New York mom, and when this bumptious lady got a good look at Mrs. B she demanded the principal transfer her daughter to another teacher immediately. Perhaps I should have done that, too. So maybe there are advantages to having a Tiger Mom?

Nevertheless, I tend to veer towards backing away and letting my daughters take care of their business themselves. As they get older I want them to get to the point where they direct the majority of their affairs without parental help; this is how parents, in a best care scenario, make themselves unnecessary. I have always thought that parents should gradually give their children more and more freedom, up until the point where children are used to and capable of acting as adults themselves (and therefore don’t end up living in their parent’s basement into their thirties). Doing too much for your children militates against your child being able to stand alone on their own feet. You juvenilize them, by doing too much. A young person does not have agency to act for themselves, and thereby learn. It hinders them from growing up. As a teacher I see this all the time. Young people need to have the FREEDOM to act on their own and maybe make mistakes (“failing forward”), having the COURAGE to go forward and embrace the world. “Go for it, girl!” is the refrain I use with my daughters. Don’t sit around the house worrying about what might happen. Get off your butt and do it. Be active, not passive. Put the damn cellphone down and go outside and get ‘er done! Simple enough.

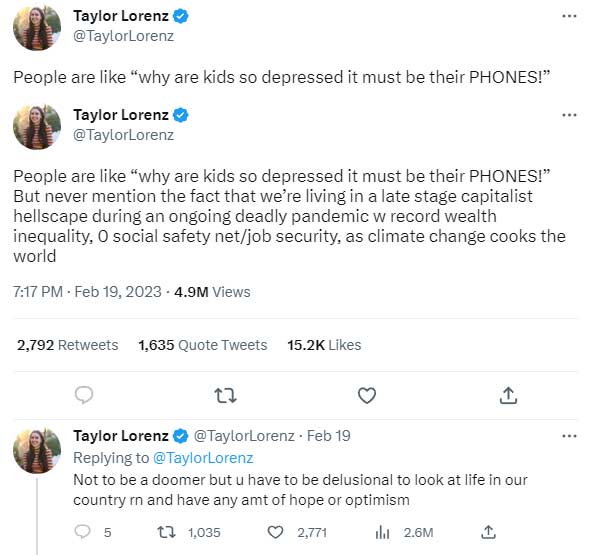

So I urge my daughters to stay positive moving forward, ignore negative people, minimize taking offense from others, take full advantage of opportunities, and to control what they can control while ignoring the rest. This is almost the opposite of what I see from many who almost seem to highlight the negative, dwell on the combative, and catastrophize the slights and injuries of everyday life. Especially on social media, especially when talking about politics, there is a whirlwind of extreme pessimism at play. Their lives are miserable and getting worse, a meme which has long since gone viral among young people on social media – “The world is horrible and coming to an end!” – take a look at the following:

Sure, we have problems, but Taylor, and “doomers” like her, make these problems way worse than they actually are. It is almost as if they are encouraging emotional thinking and resulting anxiety/depression among young liberal people. And so the mental health stats for young people – and especially teen girls – is off the charts! And then I have noted with apprehension how the language of therapy has entered the mainstream lexicon. Trauma, PTSD; anxiety and depression. It seems to be everywhere; there is a mental health “crisis.” Look at the recent cover of a newsmagazine I subscribe to –

The statistics for teens with mental health crises are sky high – especially for teenage girls. Look at the commentary as to reasons why –

Look, if you have serotonin issues and are mentally ill, then get all the professional help you need, by all means. But don’t let the usual scrapes and bruises of daily life convert into a mental health crisis; show resilience, instead. When adults highlight how horrible the world is (“catastrophizing” reality), and incorporate the language of therapy into daily life (“trauma,” “anxiety and depression”), they are embracing negativity in a self-indulgent feedback loop. The distressed mental outlook totally translates into a powerful physical reaction – adrenaline pumping throughout the body in a “fight or flight” physiological response, in an unsustainable and unhealthy state of mind and body. It is almost as if in highlighting the threats, they increase the sense of threat. The end result is to increase the fragility of young people.

Adults are partially responsible for this, in my opinion, for not modeling how a well-adjusted adult deals with conflict. When upset college students demand that a professor or guest speaker be censured or banned from campus to “protect the well-being of the community,” they often find the administration agreeing with them. “Yes, it is horrible he said that! It is damaging. No, we can’t allow that!” Look at how writer Jill Filipovic critiques how liberal American university administrators are partly responsible for helping students to catastrophize their grievances wherein young Americans who identify as “progressive” complain about being the “victims” of various “microaggressions” and “racist/sexist/ableist language” on campus and in society, and the college indulges them in their self-pity and demands for “accountability”.

I am increasingly convinced that there are tremendously negative long-term consequences, especially to young people, coming from this reliance on the language of harm and accusations that things one finds offensive are “deeply problematic” or even violent. Just about everything researchers understand about resilience and mental well-being suggests that people who feel like they are the chief architects of their own life — to mix metaphors, that they captain their own ship, not that they are simply being tossed around by an uncontrollable ocean — are vastly better off than people whose default position is victimization, hurt, and a sense that life simply happens to them and they have no control over their response. That isn’t to say that people who experience victimization or trauma should just muscle through it, or that any individual can bootstraps their way into wellbeing. It is to say, though, that in some circumstances, it is a choice to process feelings of discomfort or even offense through the language of deep emotional, spiritual, or even physical wound, and choosing to do so may make you worse off. Leaning into the language of “harm” creates and reinforces feelings of harm, and while using that language may give a person some short-term power in progressive spaces, it’s pretty bad for most people’s long-term ability to regulate their emotions, to manage inevitable adversity, and to navigate a complicated world.

Jill Filipovic “Fear of a Female Body”

The end result is young people who are stressed, exhausted, and see themselves as in danger of going under – “I am mentally unwell!” “I am a victim!” “Trauma!” “America is a hellscape!” “I am so burned out!” “It is so hard!” “PTSD!” – and the college opens a classroom as a “safe space” for tearful students to gather and recover as a controversial speaker makes a presentation nearby on campus. (“I’m traumatized by their presence near me!” “Stochastic terrorism!”) One can view this progressive zeitgeist of tight-lipped fatalism freely on the Internet, where you can see the waves of unhappiness among young people – especially teen girls, especially among the “woke” – in their social media postings, especially when it comes to politics and political controversy, where there is an extreme pessimism and negativity at play, à la Taylor Lorenz. The sentiment is often encouraged and seconded by adults in charge, in American schools and in colleges, with too many Americans claiming to be a “victim” of something where “we live in a world where the emergency room is filled up with mother*#*kers with papercuts,” as comedian Chris Rock recently described it –

Yes, we live in the Age of Grievance, where everybody is offended and outraged about something, jeez. I have heard many decry these grievance-mongers as “snowflakes,” ready to meltdown when confronted by pressure and difficulty, and that label all too often is not wrong. Whatever else they might be, such young people are FRAGILE.

But I want my daughters to be anti-fragile, not fragile. So as a dad I act on that understanding. My daughters have agency; I give them the freedom to control the course of their lives. They are up to it; I will urge them to reject helplessness or hopelessness. I hope to model this outlook in our family life. This is important. This is fundamental.

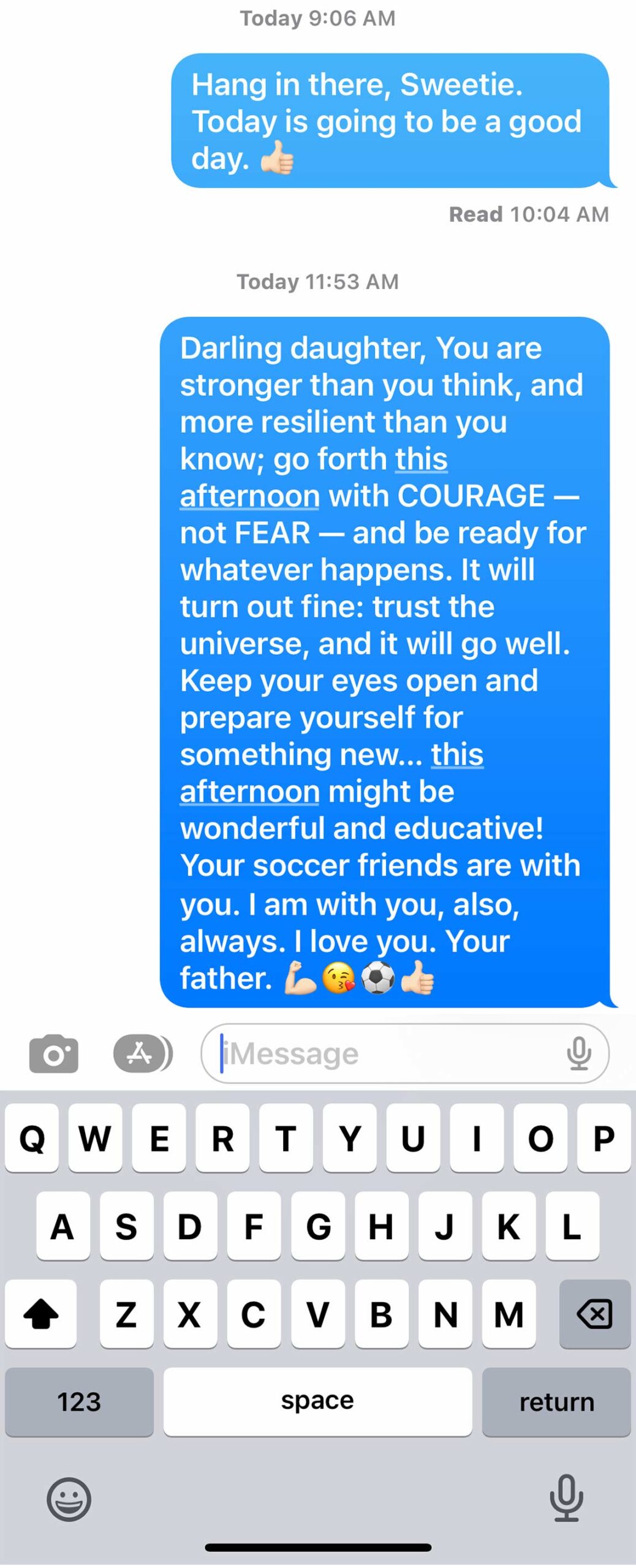

Let me be specific. My 13-year old daughter was in tears this morning about a new development with her soccer team which she took to be threatening and stressful. I sent my apprehensive daughter the following text message while she was at school beforehand:

After sending it I was pretty proud of this text and my parenting effort. But later that day when I asked her excitedly how it went, my daughter admitted she had not read my text because “it was too long.” So I was humbled as a parent yet again, alas.

But she did well that afternoon, and none of her fears came to pass: another challenge confronted successfully. My daughter gains confidence through struggle in her childhood. Learning to confront and overcome difficulty and anxiety is important because success is a habit in life, as is failure. My daughter is learning to overcome. She will hopefully become one of those adults able “to regulate their emotions, to manage inevitable adversity, and to navigate a complicated world,” as Jill Filipovic stated. My daughter is approaching that moment in her upbringing when I can safely say she is “well launched,” or so I will hope.

So I will stick with my laissez faire parenting. I always liked the statement “Prepare the child for the road, not the road for the child.” But these helicopter parents do just the opposite: they “prepare the road for the child” by seeking to remove all the obstacles out of the way of their children (ie. “snow plowing”), rather than working with their child to figure it out by themselves. I have met numerous high-pressure moms who ask me (a public school teacher) a thousand questions about the pros and cons of the middle and high schools in the area, seeking to have their child attend the best one. I think to myself these neurotic moms should spend less time and effort researching prospective schools, and more time preparing their child to put forth their best effort at whatever school. “Your son’s future school is not the problem,” I think to myself. “Your son is the problem.”

Fellow parents, do what you can to improve the world, by all means. But you can do only so much at the macro-level. (“Control what you can control.”) So I urge you to prepare your child to become a strong, nimble, ambitious, and resilient young adult capable of successfully navigating the “complicated world” as it is. As Thomas Jefferson said, “Nothing can stop the man with the right mental attitude from achieving his goal; nothing on earth can help the man with the wrong mental attitude.” In about a thousand different ways, this statement is so true.