There are moments in youth when you make choices that alter the trajectory of your life. You might not recognize it at the time, but years later you can appreciate where a turning point took place. In this essay I will explain how my life changed so much for the better when I decided to teach myself Spanish. With a first few steps I undertook a journey which would be long, difficult, rewarding, adventuresome, and wonderful. It would change my life.

I studied French in high school and college. I enjoyed learning the language and culture, but I did not find much use for it.

I spoke some French when I was a tourist in France for a few weeks. But that was not much.

I live in an area with many more Spanish speakers than French speakers.

So what does this mean, in practical terms?

Well, I found myself sitting at the triage desk at the UCLA Emergency Room around 1990 in a job I had while a college student. A pair of worried immigrant parents would often come to the ER in the middle of the night with a sick baby, as they often had no health insurance and nowhere else to go. So they came to the emergency room for help.

And they sat down in front of me and tried to communicate. It did not go well. This immigrant mom from Mexico would sit rocking her crying baby while trying to speak Spanish with me. I didn’t understand. I tried to speak some English with her. She didn’t understand. We both sat there more than a little embarrassed. In desperation I tried speaking some French to her. “They are both romance languages with similar Latin roots. Maybe French would be recognizable to Spanish speakers?” No, it wasn’t. She didn’t understand any of my French. Nothing. Total failure.

So I would go excuse myself and go scare up a Spanish-speaking employee who could help them.

But it rubbed me wrong. I sat there trying to communicate with this lady about her sick baby without any success. It was frustrating. It happened relatively often.

I also had a fair amount of time at that job in the ER where I was often just sitting there waiting for something to happen. I had some spare time.

So next time I was at my parent’s house I borrowed a high school Spanish textbook I found lying around. My brother never returned his textbook to Corona del Mar High School, and I took possession of it. I started reading it. I put my spare time to good use. I took that surplus high school textbook and started teaching myself Spanish in that emergency room. This was the humble beginning of what would become a very long journey.

Decades and decades from that time and after thousands and thousands of hours of study, I am reasonably fluent in Spanish. It has been quite the adventure. In fact, it would not be going too far to say that it has changed my life. Learning Spanish has been worth every hour spent and every ounce of energy expended.

I will even say this: I have done almost nothing more enriching in my life than to learn the Spanish language. To learn another culture, to be able to dream in it, to eat its food, read its poetry and politics – to grow to see the world from a larger perspective – these have all been wonderfully enriching experiences.

But they had to be earned. I learned Spanish the hard way. I never studied Spanish in a traditional classroom – I am self-taught. I never learned under formal teachers via approved curricula. But I found teachers and support everywhere I went. I searched out and found what I needed.

The Spanish language – like all the others – is not a secret. If you want to learn it, you can do so. Nobody is stopping you. The task is not any easier or harder than it is. It does not cost much money. But it will cost you blood, sweat, and tears. There is no getting around that. Are you willing to pay the price?

I never thought to go the “easy American” route. I was not going to download Duolingo on my iPhone, and pretend that the software would teach me Spanish. I had no pretensions that purchasing the Rosetta Stone computer program would do much – I was not going “to learn Spanish in 60 days!”, mendacious modern marketing notwithstanding. I disbelieved such a fantastical claim on principle. As I have said before, anything worth doing should be difficult, not easy. Anyone claiming otherwise is lying and/or trying to to you something.

So what did I do?

I wrote out the rules of grammar and studied them assiduously. I made piles and piles of handouts with vocabulary. I would write the verbs and nouns over and over again until I had them good and memorized. I always read the local “La Opinión” Spanish-language newspaper for a few years in the mid-1990s; it was not a stellar newspaper, but it was cheap and printed new everyday. And it was in Spanish. And then while in my car I listened to the radio talk shows in Spanish for years. All added together I must have listened to thousands of hours of Spanish over my car radio. I marinated in the stream of spoken Spanish, I just absolutely marinated in it. On the Spanish-language radio I heard the breathless breaking news of the murder of the popular singer “Selena” in 1995 – someone I had never heard of before. In this same fashion I listened to the news of the “Zapatista” uprising in Chiapas, Mexico on New Year’s Days in 1994.

At the beginning, it was rough going. I understood next to nothing. The conversation seemed like a lighting-fast rattle of one word which blurred into the other in an incomprehensible stream of gibberish. Ta-taka-ta taka-ta-taka-ta-ta – that is what Spanish sounded to me at that time. Frankly, reading the newspaper was not so different. I could comprehend only a small minority of the words in any article. I would be left to guess at the larger message from the context of the words I could understand. But I would have shrunk in shame from using some watered down Spanish-meant-for-learners. “Don’t give me anything less than the real thing,” I thought to myself. Give me the real world of Spanish speakers, and I will adjust upwards to it. Give me nothing less. If you give me time, I will get there. I can do it.

So over the months and years of incessant, conscientious study I improved. What was difficult was no longer so. What had been incomprehensible before, I understood at least some of it. Over time I came to understand more and more. Progress might have been painfully slow, but it was constant. I made some Spanish-speaking friends from Latin America who were only too happy to speak Spanish and help me; I am so thankful for the language help and the gift of their friendship. I also started reading poetry from the Golden Age of Spain, and it was like discovering Shakespeare anew in another language. I read Isabel Allende from Chile and Gabriel García Márquez from Columbia. I read Mario Vargas Llosa of Perú and Carlos Fuentes of México. Their books were a hard slog for an adult learner of Spanish. But I learned. Slowly but surely I grew more capable. I did not understand these books as clearly as if I would have read them translated into English, but I got most of it and that was enough. It helped that I was a competent reader in English and had solid literacy skills generally. But I never really understood grammar before I learned a second language; in learning Spanish (and French) as an adult, I came to appreciate the grammar in my mother tongue English much more deeply. Regardless of any external benefit or material reward, learning Spanish was nourishment and exercise for my brain.

After I graduated from college and stopped working at the UCLA Medical Center I got a job nearby at Nikken, USA in Westwood Village working as a bilingual customer service representative. This was back in approximately 1992. I was not really “bilingual” yet, but I got the job anyhow and spent my days taking orders in Spanish from Puerto Rican customers who were buying these sketchy magnet products in a sketchy multilevel marketing company which Nikken was. I could see almost right away that my job taking orders over the phone was a dead-end waste of my time. So I made the most of it by festooning my work cubicle with Spanish grammar diagrams and lists and lists of vocabulary words. I spent approximately a year at Nikken doing my best to improve my Spanish. Some days my jaw muscles would ache by the end of the day, as the unfamiliar “r’s” and other sounds in Spanish would force my mouth to work in ways unfamiliar to English-speakers. My brain would be exhausted by the time I went home at night. The struggle was real, but I embraced the struggle.

It was my struggle and only my struggle. Nobody among my family or friends spoke Spanish fluently. Nobody in my circle of acquaintances had much experience with any Spanish-speaking cultures. I was on my own. I chose this route. I would travel it. I could do this. I would learn.

I began to notice something important: over time it got easier. Conversations at a party on Friday night in Spanish which previously would have cost me much energy now were easier. It is not dissimilar to how I used to strain to bench press 250 pounds, but over time it became easier as the muscles grew stronger; they grow and adapt. A year or two later you can lift that much weight without difficulty. Or how at the beginning running three miles was hard as hell, but six months later you can complete it and feel as if you are just getting started. You get used to it and improve. In exercise physiology this is called the “principle of adaptation.” It is not dissimilar in the disciplines of learning foreign languages or anything else. With effort and persistence one becomes stronger and smarter – more proficient and more capable. But nothing is free. You have to earn your way. The price? Your blood, sweat, and tears.

I was willing to pay that price. Hour after hour after hour of patient study. Frustration. Patience. Effort. Progress. I taught myself Spanish – por mis puños – “by my fists.” To be an autodidact might mean the learning is twice as slow, but whatever is learned sticks twice as long. In fact, it never leaves you. Spanish never left me. “I was changed forever” might sound hyperbolic, but it is not saying too much. Perhaps this is because I worked so hard for so long at it.

I hated that job at Nikken taking orders on the phone for eight hours per day. I looked at my co-workers, my working conditions, and knew I could do better than this. So I passed all the preliminary government exams and signed up for the college courses and got a job as a public school teacher. I chose to go work in the most intense immigrant neighborhood I could find in Los Angeles in the Pico-Union area near downtown where I could work with the Spanish-speaking community. I was offered a job at Berendo Middle School. Populated almost entirely by impoverished Latino students, there was pretty much two groups of students there: those who were born in the United States to parents from Latin America and had spent their entire lives in American schools and were reasonably fluent in English, and those who had come north from Latin America more recently and were English language learners. I preferred working with those who had just arrived to the United States, as I could teach them English but still speak in Spanish often – and they usually had not adopted yet any of the American street-gang ethos which was elsewhere so dominant on campus. The new arrivals were usually nicer kids, and they were so desperate to learn English. It could be an entirely different vibe working with more “Americanized” Latino students who could speak almost perfect conversational Spanish and English, but who often cared little about learning either more deeply in an academic setting (re. serious books and complicated ideas).

So I worked at Berendo Middle School for three years. I continued learning Spanish. This is the good about being immersed in a work environment where Spanish is needed: you speak Spanish when you are in a good mood and want to, but you also speak Spanish when you are tired and would prefer English as it is easier. You are surrounded by Spanish on all sides all the time, like a fish in the water. That is how you learn. Immersion.

I know only about a hundred of my friends who took years of Spanish in American schools and can order a beer and ask where the bathroom is in that language – and that is about it. Despite years spent in Spanish classes, they can hardly speak it at all now. Or I encounter high school students in their second or third year of Spanish who study it almost every single day, and they can barely sustain even a basic conversation. It is sad. But then are they really making a genuine effort to learn Spanish as I did? Or are they just taking a Spanish class because they have to and so don’t really make the necessary effort to learn it for real?

Maybe they should forgo the Spanish class and just travel more in Mexico or Spain?

I try and speak with my daughter who is in her second year of Spanish, and she can’t (yet). I joke that I will find a handsome Spanish-speaking boyfriend for her who speaks no English. “El amor es un buen maestro.” Maybe we just need to spend a few months in Latin America? A few years?

Well, that might be coming up.

But let me finish the first part of this tale.

I have never done anything in my life more difficult than teaching at Berendo Middle School from 1993 to 1996. I tried to act as an agent of literacy in the service of reading good books and writing insightful English in an inner-city immigrant setting of poverty, struggle, and low academic achievement. There was this one worker at Berendo who did nothing all day but paint over graffiti on campus, and he assured me that if he went away the school would be completely covered in graffiti in one week: that tells you pretty much all you need to know about Berendo Middle School. Books and reading were a hard sell when I was a teacher there. Literacy rates were low and crime rates were the opposite. Everybody there seemed to struggle. I struggled.

What was I doing?

I did not labor for years in graduate school to become a credentialed teacher for this, I thought to myself; I had more respect for myself as a professional than to work in the Los Angeles Unified School District long-term. I knew there were greener pastures for me elsewhere.

So I evolved into a teacher who worked with high-achieving, mostly-monolingual English-speaking students in more prosperous surroundings. I never advertised to my new bosses that I spoke Spanish at all. I feared I would find myself in the poorest area of town working with the most needy students who were likely uninterested in buying what I was selling (ie. books and literacy). No, thank you. Been there, done that. Not interested.

So my efforts to learn more Spanish were reduced considerably. And my interactions with the local Spanish-speaking community dwindled to next to nothing. So it went. The world continued moving forward.

I got married.

I had two daughters.

I taught Advanced Placement and college preparatory classes for almost two and a half decades in the suburbs at a prestigious “magnet” high school in the suburbs.

And I came close to retirement.

My Spanish languished, but it did not disappear. Having taught myself so hard for so long – “por mis puños” – I would own it forever.

And now as I begin to prepare for the next stage of my life – an empty-nester, a young-ish retiree – I have renewed my attention on the great language of Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra and life in the widespread Spanish-speaking world.

Read Part II, of this essay.

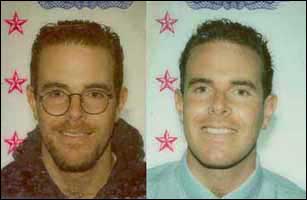

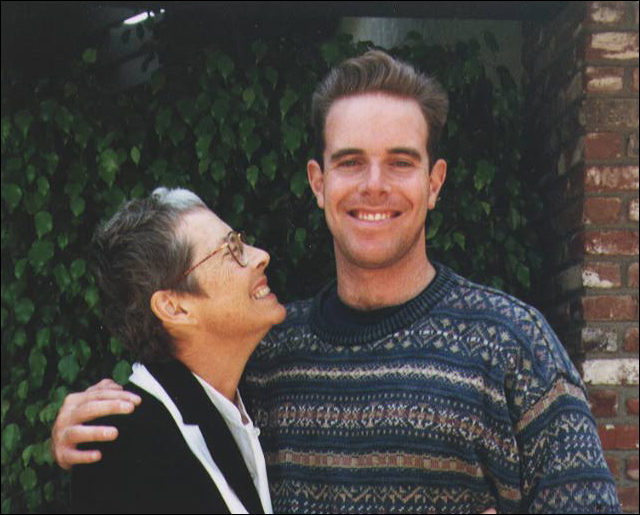

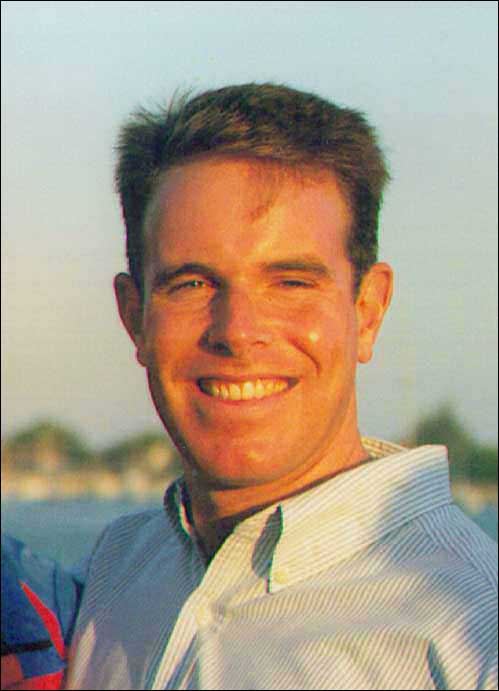

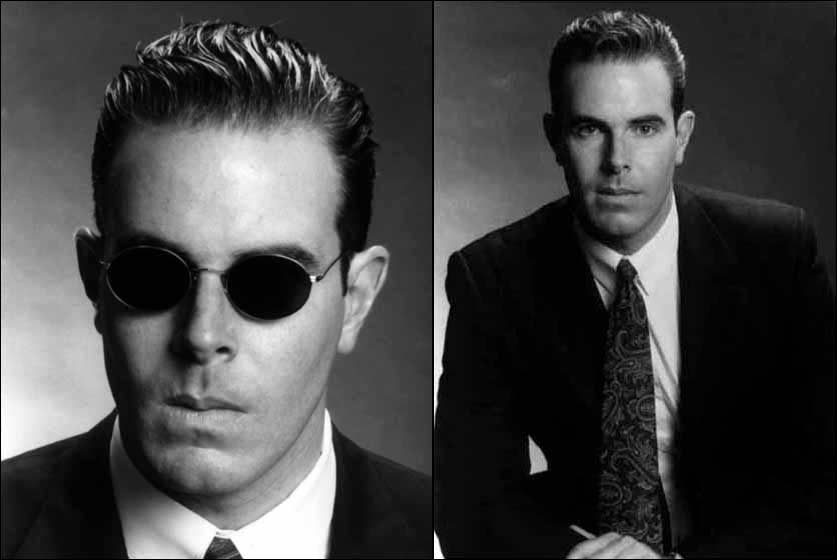

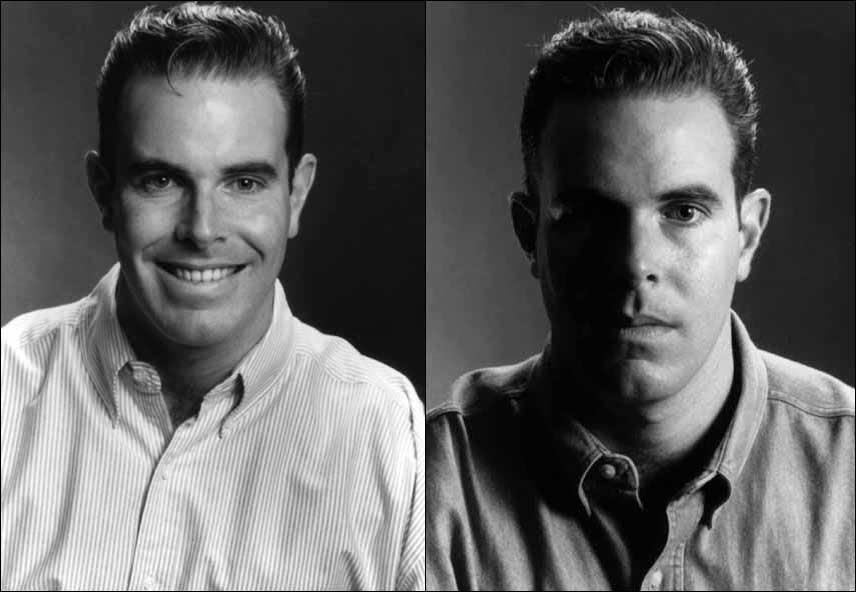

MYSELF DURING THE YEARS OF SPANISH-LANGUAGE “HEAVY LIFTING” STUDY (1992-1999)