I did not receive an inferior college education in the years I spent in the University of California system. I read the important books on a subject and heard experts in the field deliver lectures. There were usually breakout discussion sections led by graduate students. Then we wrote essays and research papers on the material. Lots of them. Lots of reading and writing.

What I tell my high school students: if you can read complex texts on complicated topics and weigh and consider different arguments, and if you can explain your thinking in clear standard academic prose — you will be fine. If you struggle to understand what you have read, and if you have trouble writing clearly and intelligibly — well, college might be a struggle. That is how it is in the humanities, at least, in my opinion. The hard sciences might be different — your mileage may vary.

The problem was that I had these giant classes in lectures halls with a professor talking to/at several hundred students. It was very impersonal. It was like you were cattle herded into this giant auditorium and you received basically zero personal attention. One hears stories of row after row of semi-interested undergraduates checking their social media feeds or the sports scores on their laptops as professors drone on and on in front of them. The professor is interested in his or her own research, not primarily in teaching — especially undergraduate teaching. Many professors have never been trained in pedagogy and have not thought deeply about it. Writing papers and books gets a professor promotions, not teaching. It are graduate students teaching assistants (“TA’s”) who engaged undergraduates in discussion sections and grade their papers, not the professors. The TA’s lead these smaller discussion sections not necessarily because they want to — they do it as a sort of “indentured servitude — to get breaks on their own tuition, as a way to make graduate school affordable, to help research universities get through the unglamorous, unrewarding job of teaching undergraduates. It is a necessary evil for them. Everyone admits the system is less than ideal. But it saves costs and make college affordable at large institutions, like UC Irvine and UC Los Angeles when I studied there three decades ago. I am sure it is much the same today.

A much better way is to have much smaller classes with intense interaction between students and professors. “Elite” private schools do this. It is more expensive. It is what my sister saw at Stanford University. Graduate courses at UCLA supposedly have smaller and higher quality mentoring of students — major research schools admit that undergraduate teaching is not really their thing. Maybe one might have some smaller upper division undergraduate classes at UCLA — but graduate school seminars and one-on-one research with a professor is their priority. But the much more intense interaction with a professor in the prestigious liberal arts colleges can yield better learning results. This is what one see at Williams or Amherst College. Students can thrive when directly engaged by professors in the more intimate settings of an elite private school. But it is the lower professor-to-student ratios make such schools more labor intensive and expensive. (As of this writing, tuition and room/board at Amherst College is $71,300, according to a quick Google search.) Maybe, like in so many other areas, you get what you pay for.

But even in these smaller private universities, the paradigm is almost always the same: read seminal works, discuss them with a professor and your fellow students, and then write long essays and/or research papers. This emphasis on lecture, with maybe some discussion added onto it, has been the format for university teaching since literally the Middle Ages. Look at a lecture at the Sorbonne in 1319 and it would look much the same as what you might find in a college lecture hall in 2019.

There is nothing necessarily wrong with this.

But there are so many other ways to teach and learn. Real life simulations, role playing, demonstrating learning via other ways than writing papers, etc. Part of the joy of being a teacher is that you can do almost anything — be incredibly creative in how you have students learn/teacher. As a high school teacher of 25 years and an adjunct education professor for 10 years, I know this in my bones. But good teaching takes hours and hours of planning and thinking by the teacher — a high level of knowledge of the subject matter coupled with solid training and experience in pedagogy. In the UC system I was always impressed with the knowledge of my professors, not always impressed with their teaching skills other than lecturing. But that was enough: I can remember whole stretches of brilliant stretch of outstanding lectures to this day — Joyce Appleby speaking on the American Revolution, Eugen Weber on Western Civilization, E. Bradford Burns about Latin American history (“theory of dependence”), Steven Spiegel on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and David Rapoport and political terrorism. I was lucky to have been able to learn from such world-famous scholars. I knew this even at 21 years of age, although I did not appreciate how lucky I was until many years later.

These UCLA professors spent the vast majority of their time researching and writing for their peers in professional journals and in books. This is how they worked to gain “tenure.” It is why they became famous scholars. They maybe arranged a few notes in preparation for delivering their lectures but that would be it in terms of preparation. Teaching was far from their main focus in the UC system; they consider themselves researchers first, teachers a distant second. And they rarely actually spoke with and/or held discussions with undergraduate students. I never once spoke personally with any of those professors I mentioned. When I was in their class they could not have picked my face out in a police lineup. The delivery of subject material was excellent; the personal attention given to me was execrable.

And that was in the “best case” scenario. There is a worst case, too.

I remember one professor at UCLA giving lectures on astronomy which were unintelligible. This professor, from a country in Asia, was a standout astronomer, I am sure. He probably had made important discoveries and achieved success in peer reviewed journals. But he did not speak English clearly and could not communicate well through a lecture. As a student I was not well served by some famous astronomy researcher who could not teach his way out of a paper bag. I struggled in that class. And I am far from the only college student with such a story. There is a crucial difference between someone who is a brilliant scholar in their own learning, and someone who is brilliant at teaching that learning to others. The two processes are not the same; they require different skill sets.

So I would give UCI and UCLA, the two universities I attended as an undergraduate, a solid “A” for quality of content and a squishy “B-” for quality of teaching overall.

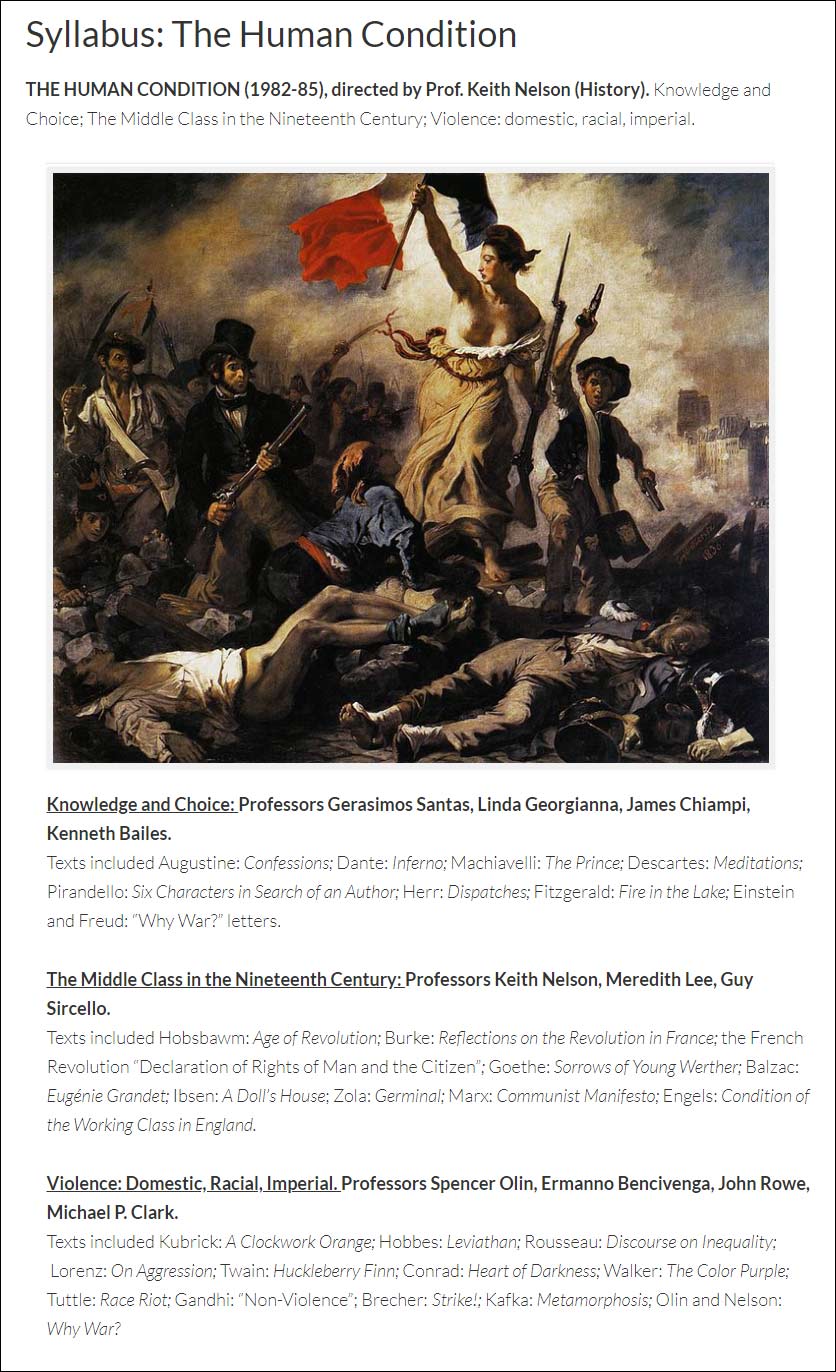

But I would take a minute to talk about the best class I took in college. I was as a freshman at UC Irvine when I took the “Humanities Core” classes over three quarters (one academic year of study). The course, set up by Professor Keith Nelson, was about “The Human Condition” and was a full 8 units — the equivalent of two classes and satisfied both the English and social studies general education requirements at UCI. This year long course of study in 1985-1986 was broken into three parts:

- Knowledge and Choice: Professors Gerasimos Santas, Linda Georgianna, James Chiampi, Kenneth Bailes:

- Texts included Augustine: Confessions; Dante: Inferno; Machiavelli: The Prince; Descartes: Meditations; Pirandello: Six Characters in Search of an Author; Herr: Dispatches; Fitzgerald: Fire in the Lake; Einstein and Freud: “Why War?” letters.

- The Middle Class in the Nineteenth Century: Professors Keith Nelson, Meredith Lee, Guy Sircello.

- Texts included Hobsbawm: Age of Revolution; Burke: Reflections on the Revolution in France; the French Revolution “Declaration of Rights of Man and the Citizen”; Goethe: Sorrows of Young Werther; Balzac: Eugénie Grandet; Ibsen: A Doll’s House; Zola: Germinal; Marx: Communist Manifesto; Engels: Condition of the Working Class in England.

- Violence: Domestic, Racial, Imperial. Professors Spencer Olin, Ermanno Bencivenga, John Rowe, Michael P. Clark.

- Texts included Kubrick: A Clockwork Orange; Hobbes: Leviathan; Rousseau: Discourse on Inequality; Lorenz: On Aggression; Twain: Huckleberry Finn; Conrad: Heart of Darkness; Walker: The Color Purple; Tuttle: Race Riot; Gandhi: “Non-Violence”; Brecher: Strike!; Kafka: Metamorphosis; Olin and Nelson: Why War?

How cool is that?

The course of study and texts were diverse and wide-ranging, to say the least. Even 33 years later I have fond memories of wading through St. Augustine and Machiavelli — reading about the riotous sans-culottes in Hobsbawm’s dramatic account of the French Revolution, Goethe’s pathetic Werner shooting himself, Zola’s bleak and angry French coal-miners, Kafka’s Gregor Samsa waking up as a hideous bug, and the wild wild Clockwork Orange of Stanley Kubrick. I still have several of the books I bought for that course in my personal library. I must have moved a dozen times since college but I still have those books. Like a turtle and its shell I have dragged these books with me wherever I have gone. I would not part with them.

And looking back at this reading list I recognize that some of these books I have read several times since, but I did not remember that I first read them in my Humanities Core class as a freshman until I looked back today at the official syllabus. Other authors, like Marx and Engels and Freud and Gandhi, I went on to read many secondary books about. Many of the “big ideas” presented here I have thought about ever since I was an 18 year old college student in that class and was first introduced to them.

What I most admired — and found so rare in college — was the interdisciplinary nature of the UCI Humanities Core class. By designing the curriculum so that big themes and ideas were examined both from historical perspectives as well as through literature, the learning was by design going to go so much deeper — such deep learning stuck with me over time. I can still remember whole passages of that class decades later. The ideas presented in 1985-1986 never left me.

My mother died in late 1996 from cancer and I moved back to Orange County briefly to live with my mourning father. We went over together to UCI in the winter of 1997 and sat in on a few Humanities Core classes after I suggested it. Much older than the kids in the audience sitting around us, we flew below the radar and pretended to be college students, believe it or not. In such a large lecture hall, how would the professor even have known? I remember reading the assigned book Tarzan of the Apes by Edgar Rice Burroughs. African American professor Lindon Barrett then asked the class if we had liked it. I remember looking around and seeing what seemed like many students in the mostly Asian American audience raising their hand that they had indeed liked the novel. Visibly embarrassed, Professor Barrett then went on to explain why we should have been offended by the underlying racism of the book. At any rate, my father and I both enjoyed the Humanities Core lectures we attended.

I went on later to design my own interdisciplinary American studies class. As a teacher myself I tried to carry on the practice of twining literature and history into one class to present “big ideas” — important themes that show the complexity of life through individual literary characters who operate in the context of larger historical forces. It allows all involved — teachers and students — to hit that “sweet spot” of deep learning when literature and history are integrated together to portray the richness of the human experience. Interdisciplinary learning allows for the synthesis of diverse learning, rather than for isolated “snap shot” pictures of relatively superficial learning.

Why don’t all secondary schools and universities have such “core” classes where English and social studies instructors “team teach”? Where the two (or even more!) teachers seek to achieve a synthesized whole out of separate disciplines when looking at the same phenomenon?

My experience has been that it requires a degree of coordination between different teachers and academic departments that is hard to achieve. There is no good pedagogical reason against interdisciplinary learning but there are bureaucratic ones. The History and English departments are too often like separate fiefdoms and the teachers don’t know each other well. Or they don’t want to cooperate and work together. Or the academic disciplines are “turf conscious” — jealous of their territory being infringed upon by other departments. Or they can’t be bothered to collaborate — it requires too much time and energy. They have other priorities. The learning would go deeper if everyone planned and taught together with intention, but interdisciplinary courses only happen if institutions choose to create and support them. The norm is just to have each department and teacher do their own thing. But the learning suffers. I remember asking one history teacher why he did not collaborate towards integrating his class content with the English teacher across the hall teaching the same students. He told me, “We don’t have that kind of working relationship.” In other words: we don’t get along. The students consequently missed out on an opportunity to learn in a deeper and more multifaceted way. Any synthesis of learning they will have to make happen themselves without help from a teacher.

This is what happened too often with me. I remember taking a whole slew of single courses in college that, while interesting in themselves, did not build the one on the other. They were isolated, unrelated islands of learning in a trip that too often was not going fixedly in one clear direction. In the end, I had an undergraduate “Political Science with an Emphasis in International Relations” degree.

But the Humanities Core at UC Irvine was the best class I ever took.

I am still thankful over three decades later.

Thank you, UCI History Professor Keith Williams, for helping to make it happen.

And thank you, University of California at Irvine, for having given the institutional support to the Humanities Core class since 1984 (the year before I took it) all the way up until today. I hope it goes on forever! Ars longa, vita brevis.

NOTE: To read more about the “big idea” themes and the different syllabi from the Humanities Core course over the past 34.5 years, check out the official class link.