Trudy Rideout went home to her maker today. She died at 1:30 pm on Tuesday October 6, 2020. This ends a life that started on March 11, 1940 in Chicago, Illinois.

Trudy was my stepmother, a much maligned family role in our popular culture. The negative trope in society is the sullen teenaged girl resentful at her father’s new wife — the stepmother. The daughter does not want a new “mom,” and she makes her feelings known. In contrast, I enjoyed my stepmom and was grateful to have her in my life. I never thought she would replace my mom who died twenty-three years ago when I was 29-years old, but I appreciated her mother-like presence in my own life, and in the lives of my wife and daughter. When Trudy was diagnosed with a return of breast cancer in July of 2016, it was a blow to all of us. Watching my second mother-figure struggle with and then succumb to cancer has given me more than a few moments of déjà vu and reflection about the finite nature of our mortal lives, and this is the larger point of this essay. Two mother-figures dead of cancer, eaten up by tumors, radiation and PET scans, immunotherapy and chemotherapy — clinical trials and rumors of clinical trials — wasted away patients who weighed maybe ninety pounds with no hair by the end. The cancer, it eats you away.

Cancer. Two times.

Oh, how I am sick of cancer and cancer treatments.

In the last century we humans learned to outsmart and survive smallpox, diphtheria, and tuberculosis in youth and middle age. We developed vaccines and antibiotics. But that just means we often live long enough to get cancer — the “emperor of all maladies.” Cancer, alas. It would seem we moderns have extended the length of our human lives. But whether we have extended the quality of life, with all these wasting diseases like cancer, is debatable. We live long lives; we die long deaths.

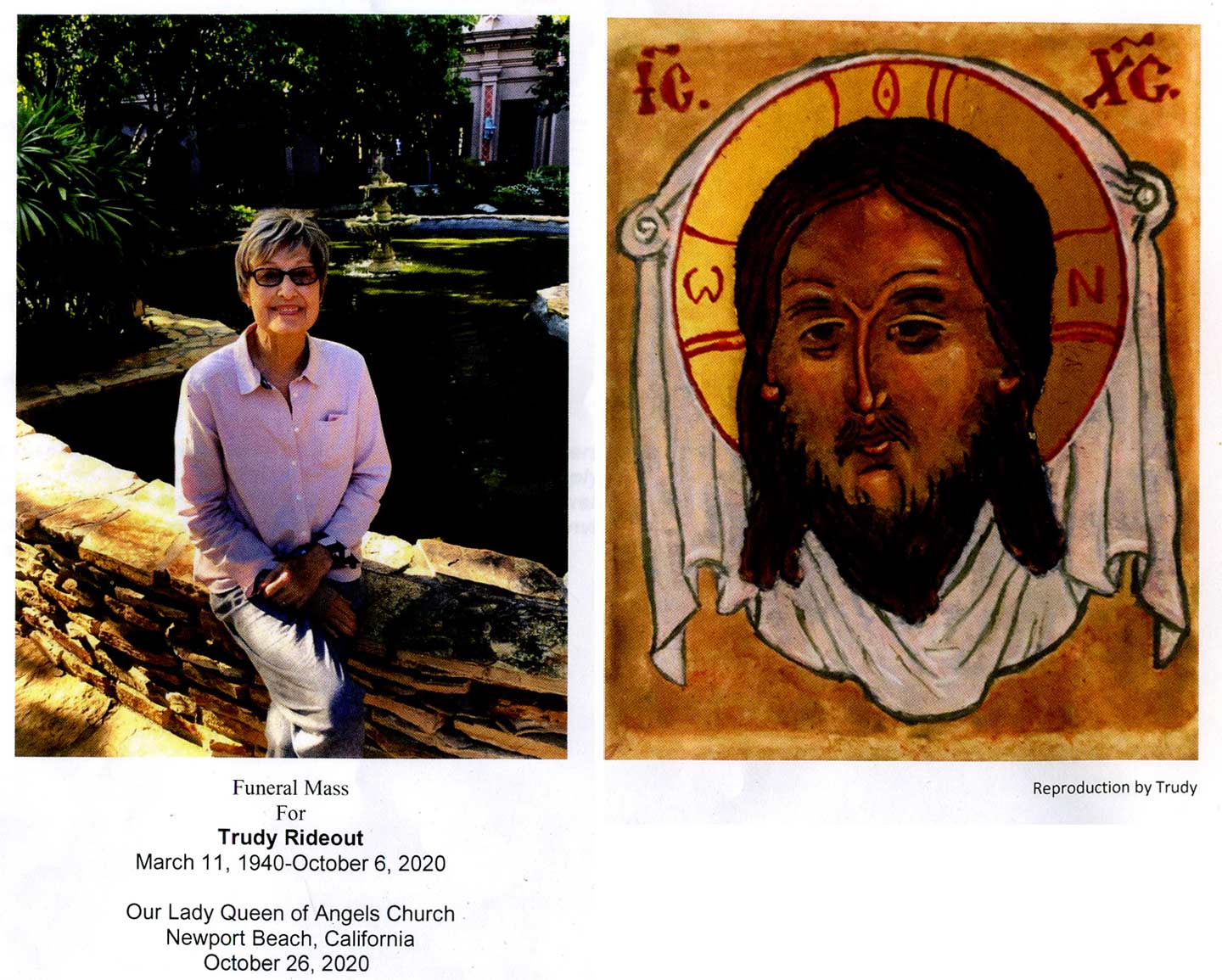

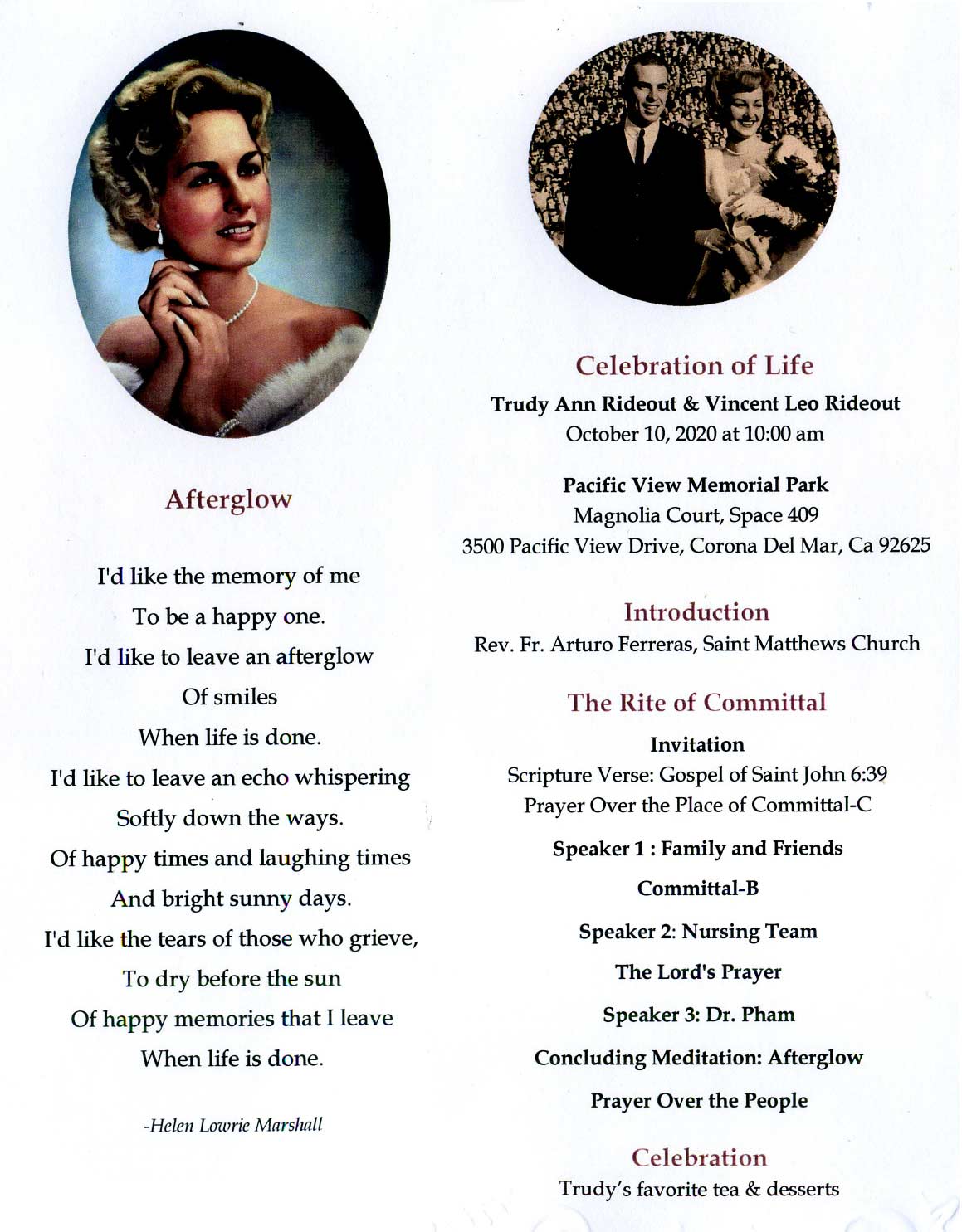

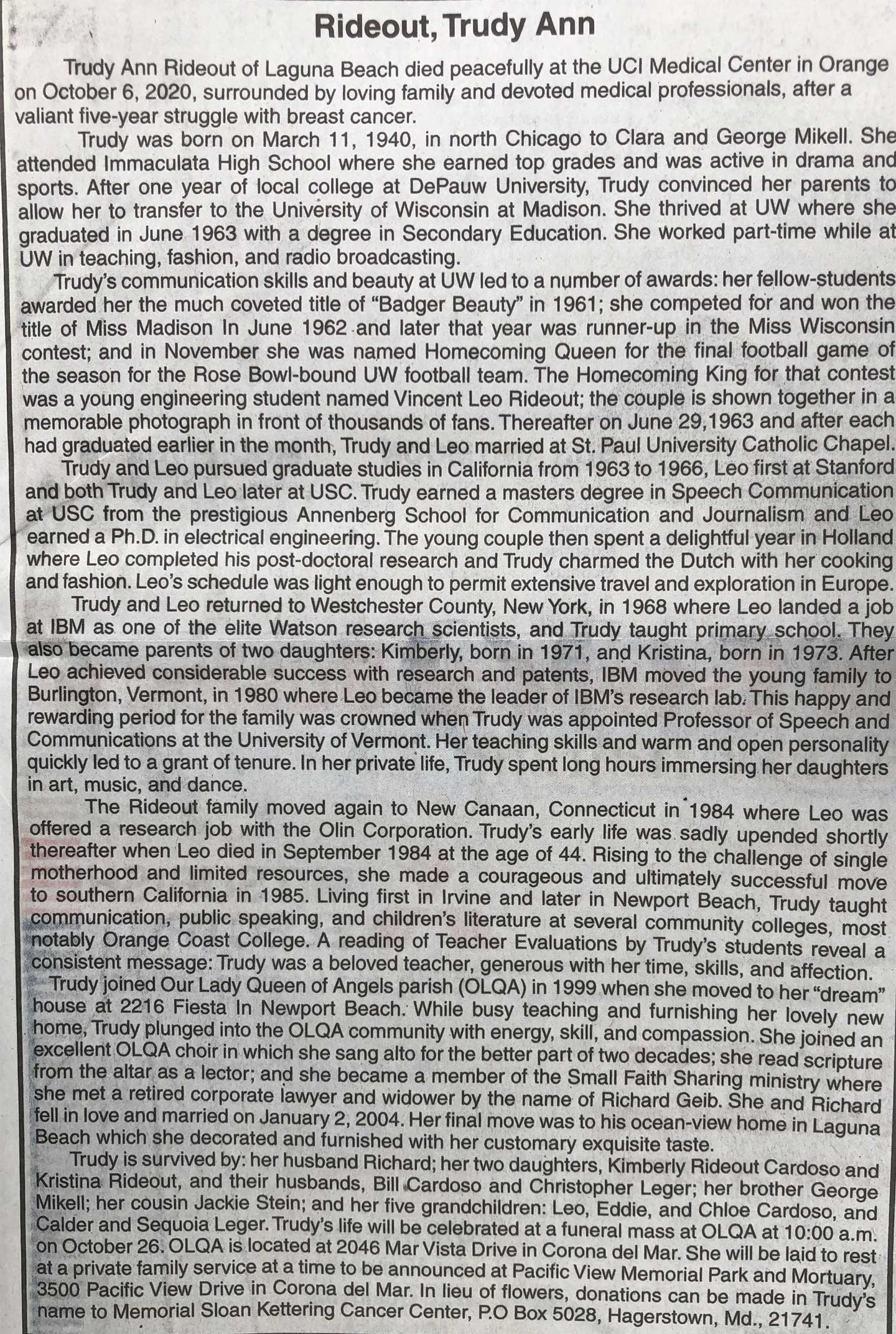

But first a brief re-telling of the story of Dick and Trudy. My widowed father was a single man some four years after his first wife died in 1996 before he met his second wife, Trudy. Before finding her my dad dated dutifully with more success or less — there were good dates and bad dates. But after four years with no long-term relationship on the horizon, my father seemed to have given dating his best effort and failed. He was still unmarried; he was frustrated.

My father seemed ready to give up. Not long before he met his second wife, my father tearfully confided to me, “I don’t think I ever will meet another woman I can share my life with again, Richard. I will be alone.” Not long after that he met Trudy, the second great love of his life. My father is the type of man that does much better with a woman in his life, relationship problems and all. Trudy was a godsend to him. Whenever spousal difficulties would arise in his own marriage or those of his children, my father’s words and actions were always the same: “Talk it out. Sit down and talk through your difficulties.” You didn’t just walk away. In the last few months of their lives together, Trudy and my father occasionally saw a couples therapist together that was equal parts relationship and grief counseling. Do you think that getting sick and dying puts stress on an intimate relationship? Yes, a lot. I saw this with both my mother and step-mother: dying people often strike out in anger at those around them, and the closer the person the more they get the brunt of this anger. But Trudy and my dad sought to work through it to the end.

Or to be more accurate: the bittersweet end. Very bitter. Very sweet. Emotionally superheated moments of deep pain and loss inextricably tied to feelings and expressions of deep love and connection. My mom accepted her imminent death, refused any further medical treatment, and died at home. Trudy, in contrast, fought her disease almost to the very last. She did not go home to die but went to a skilled nursing home where her days were occupied by intense and desperate medical measures in a last ditch effort to buy time. And they did buy time — a couple of months. But by the end Trudy was in pain, exhausted, and worn down. She died in the UC Irvine Medical Center ICU. The contrast between how my mother and stepmother died could not have been more stark. My mom was only 56-years old when she died, and I still feel that was too young. Trudy, on the other hand, was 80-years old, and so I feel less aggrieved by her death. She had led a long and full life.

But for both my mom and stepmom the end was the same. It will be the same for all of us, sooner or later.

Trudy and my father were married for 16 years.

Soon after they were married on January 2, 2004, Trudy had her first breast cancer illness. My father could hardly believe it! Trudy got treatment for her cancer and it seemed to be in remission. There was a pause of almost a decade and a half where my father and Trudy were able to travel and enjoy their lives together. They were in their seventies, had enough money and then some, and were surrounded by good friends, children, and grandchildren. Life was good. Trudy was family to us. My father’s wife, my stepmom. Birthdays and holidays and the birth of my daughters. Trudy was present for all of it.

Then in July of 2016 the breast cancer came back, and it had metastasized with secondary tumors on the hip bone and spine. There was a quick double mastectomy, and then a long wearying line of medical interventions. Compared to my mother’s medical treatment in 1996, Trudy was well served by modern medicine. My mom was poisoned by chemotherapy almost to the point of death, and then she died. Trudy, in contrast, received immunotherapy of varying sorts, and then radiation and chemotherapy that was gentler and better managed than my mom’s. Chemotherapy seemed to have greatly improved between 1996 and 2016, and there are better drugs to manage the side effects. But the end was never in doubt. They both died after their cancer (lung cancer for my mom, breast cancer for my stepmom) passed the blood-brain barrier and invaded the brain and killed them. In medical terminology, they died from “leptomeningeal” cancer. Patients nowadays who survive long-term with metastatic cancer often succumb eventually to leptomeningeal disease.

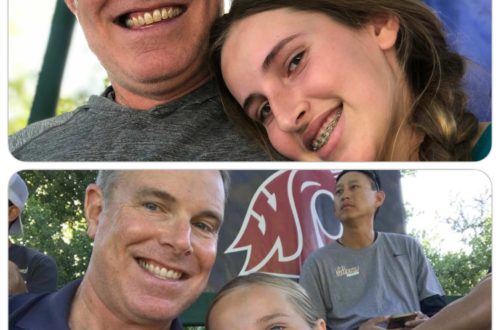

Dick and Trudy fifteen years into their marriage.

For some five years we who loved Trudy lived waiting for the other shoe to drop. I was surprised how long Trudy endured the insidious cancer cells growing in her body. She was a dedicated cancer patient who loved life and fought for it. There were few experimental trials or novel treatments that Trudy had not researched. Doctors, I am sure, both admired her ability to advocate for herself and suggest treatments, and became frustrated by her continuous phone calls, emails, and refusal to see dead ends as dead ends. One of her revered doctors in Memorial Sloan Kettering in New York wrote that “Trudy will succumb to this disease.” Trudy heard the words, but fought against their import until nearly the end. Trudy was a “high maintenance patience,” in both the good and bad meaning of that phrase. She wanted so much to live.

At the same time, Trudy’s faith was a strong armor in the knowledge that cancer would be her end. She lived over five years from the spread of cancer beyond the initial “metastatic” diagnosis , beating the majority of those with a similar illness. She did well in the long-term siege that was the fight against cancer and the tumors. My stepmother’s struggle with cancer, like my mom’s, was like the trench warfare of WWI: the tumors would be beaten back after intense seesaw fighting over a broad territory, but little by little the body would be ruined and overtaken by the onslaught. The body became the scorched-earth battlefield between pernicious cancer and modern medicine. Trudy began to wither away. This battle was not going to be won; time was not on Trudy’s side. We knew this. Trudy knew this, but she fought against it. I am not sure she ever found full acceptance of her death, not even at the end. She was caught in the coils of modern medicine and the long litany of doctor’s appointment and medicals. The medical “noise” of treatments and tests never ended. My mother, in contrast, refused all medical treatment at the end. She just focused on making peace with her end and saying final goodbyes. My mom died at home in her own bed with her beloved rose bushes just outside the window. I was in the adjacent room when it finally happened. But it would be different with my stepmother.

Hope, that feathered thing from Emily Dickinson “that perches in the soul,” was ever present for Trudy. Maybe the cancer would go into remission. Maybe there would be a new clinical trial. Maybe some experimental surgery. Maybe, maybe. She thought it cruel if a doctor would point out the obvious: this disease would kill Trudy. But the doctors did occasionally say this, and I thought that just plain honesty and good medical practice by a doctor who knew better. I had no doubt that the cancer would kill Trudy. I was a bit surprised — and pleased — she did so well for so long. Finally, on Thursday December 5th of 2019 Trudy had a seizure and was rushed to the hospital by paramedics. They found a tumor around the size of a nickel in the occipital region of her brain, and two days later they found that the cancer had spread beyond the brain to the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in her neck and spinal cord — she had the same end-stage leptomeningeal syndrome which killed my mother 23 years earlier. Here I was again with a mother-figure with brain cancer!

I could hardly believe it.

I spent 9 hours with Trudy in her hospital room that first weekend in December 2019, and we cried and talked frankly about the end. A week earlier at the Fashion Island movie cinema we had sat next to each other and watched together It’s a Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood movie and had seen a scene where actor Tom Hanks portrays Mr. Rodgers interacting with a family struggling awkwardly to talk about the impending death of the patriarch —

— and now a week after we watched this scene here we were in Room 27 of the Brain and Spinal Cord Unit on the Third Floor of the East Wing at Hoag Hospital in Newport Beach. We had this conversation —

Trudy: “I am strong in my faith, and I feel close to God. Prayer and the figure of Saint Faustina help me. But there are times when I am scared.” She said this in tears, already semi-stumbling to find the words — the brain lesion making its presence felt, a sign of impending mental function decline. Trudy could discern the outlines of her end. We knew Death, that “lean abhorred monster,” was crouching nearer to her now.

Holding her hand and looking at her, I responded: “You have excellent medical care and are surrounded by love and loved-ones. Everyone is on your side, Trudy. There are forces beyond any of our control at play here, but we will do this. We love you. You will not be alone. It will be OK.” I was crying, too.

Sitting there bedside with a dying mother-figure again, and I had given enormous thought over many years to the process of dying.

I thought I said exactly the right thing, except for maybe “It will be OK.” Was this facile for me to say? Uttering a platitude? How do I know if dying was OK for Trudy? Was I offering false hope? Attempting lamely to smooth over a rough path? Is it not for me to say if it “OK” for her or not?

On the other hand, I think it really will be OK. When a dying woman comes to accept death and makes her peace with it, when she finally lets go and moves beyond sadness and anger, then it really is OK. Death is a natural act, beyond our power to remedy, and to let go and slip away from life — Trudy, it is OK. At that moment, you can go. We release you, Trudy; you are free. Release your grip, let go. Courage, faith. So I do believe it will be OK. I hope it will be the same for me at the end.

“To One Who is About to Die”

by Walt Whitman

Trudy was 80-years old when she died. My mom died at 56-years of age, and she had cause to complain of getting sick and dying so young; Trudy was much older and had less cause to complain. She had lived a full life. She did the best she could. And her “best” was pretty damn good. Trudy, it is ok. You have earned your rest.

So I write this memoriam to Trudy Rideout. I do so to make sense of the loss and to gain closure myself. Two mothers figures, dead of cancer. Trudy was a great lady. I was glad to have known her.

Trudy lived a full and rich life of which she can be proud. Trudy’s first husband Leo died in 1986, and she was left to raise their two daughters alone. She worked as a teacher and professor on many different campuses while her daughters were in junior high, high school, and college; Trudy had earned a PhD in Communications and taught in and around those academic fields — most notably at Cal State Long Beach for many years as an Adjunct Professor training elementary teachers in children’s literature. Trudy raised her daughters Kimberly and Kris in New Canaan, Connecticut and Irvine, California, and competed in women’s 4.5 USTA tennis leagues at the Irvine Racquet Club. Later she worked at the Pelican Hill Golf Club in the pro shop where her excellent eye for clothing and style served her customers well. Year after year Trudy would buy me a button down long-sleeve shirt for Christmas, and I was always amazed at how beautiful and stylish the shirts were — the kind of clothing I seem to be constitutionally incapable of finding for myself.

I wrote about how my father and Trudy were married to the “bitter end.” That is an unfair picture of the majority of their life together. For many years they lived happily on a cliff above Crystal Cove at 488 Panorama Ave. on a hilltop overlooking the sea in Laguna Beach. They could look out at the Pacific Ocean where the whales migrated up and down the coast in the summer, or where the dolphins would play all year long. They hosted parties on their deck. They had memorable trips to Carmel-by-the-Sea, including a memorable in July of 2003 one where Dick proposed to Trudy. They went to Maui every January on vacation and stayed at the Mauian — by the end they were on a first name basis with the owners of that hotel. Our families rented a house in Carlsbad the summer of 2018. We rented another house at Sea Ranch another during the summer of 2014. We took a Disney cruise to Alaska in July of 2017. We celebrated Trudy’s 75th birthday memorably at the La Jolla Beach and Tennis Club. The list of such family gatherings is long and happy.

Trudy and my father were members of Our Lady Queen of Angels Church in Newport Beach, CA. That is where they met, and they had deep social connections to that faith community where Trudy sang in the parish choir. My father served in a volunteer administrative capacity in church leadership. They both participated in small faith-sharing groups dedicated to Bible study and discussion. Their shared Catholic faith was a strong and vibrant part of their relationship.

And her faith helped Trudy to face death. It helped my father, too, but to a lesser extent. My experience has been that couples in their 80s spend their days taking each other to their doctor’s appointments, and console each other when they are ill and in pain. I have often thought to myself how depressing it is to get old and to be sick and in pain like this. But do you know what is even more depressing? It is to be old and sick and in pain and ALONE. Part of being an aged couple is helping each other when one gets sick and dies. It will happen. Trudy made it to 80 when she faced that. Others, like my mom, face it much earlier. We can look at old age as a misery and a tragedy, but maybe we should be grateful to have made it that far. Gratitude.

We are all of us going to die. Maybe the idea is to live well before it comes time to die. To make excellent use of the time God allows us. Trudy excelled in this. She did a great job of surrounding herself with friends and living a life worth living. Trudy suffered her share of tragedy and disappointment, but she did not overindulge in bitterness, blame, or self-pity. Trudy never gave up the struggle. Trudy was usually cheerful and pleasant. She gave more than she took. She was open to new people and the ever-present possibility of personal growth and human connection. She enriched my life and that of our family. Her husband, my father, will join Trudy in God’s good time. As will I. As will Trudy’s daughters. And eventually my own daughters, too.

Death has a way of clarifying what is important and not. It gives a sense of perspective. For those attuned to it the subtle scent of death adds spice and pungency to our precarious mortal lives. Even at their biggest, most “happy” social events and parties, the ancient Egyptians supposedly parked corpses nearby to remind everyone of what comes next.

I remember watching a part of the movie Birdman when a young woman who was in recovery from drug addiction explains why she held a long thin knot of cloth with many marks written on it. Watch her explain herself —

— how true! We are so wrapped up in the minutiae and drama of our individual lives that we forget how brief and inconsequential it all is. But even if our lives are relatively unimportant, it does not mean they have no importance. Let us do the best we can where we can, and then let us exit the stage with as much grace and dignity as we can muster. (Life did not give my friend Chris much leeway in this.) Let us use our time, not waste it. Carpe diem. “Seize the day!”

One thing I have been reminding myself and my father these past few months is that Trudy’s demise and death was not preventable. We cannot avert this. Force majeure is at play; we did not have control over Trudy’s cancer and her death. Maybe rather than shaking our fists at the gods and cursing our fate, we should practice acceptance of God’s plan. It makes for good poetry to rage against the dying of the light. When initially diagnosed with a terminal illness I have heard many claim they are going to fight fervently and forever against the disease to try and stay alive. They will do everything they can to remain with family and friends in the land of the living. They won’t give up. They’ll fight. For as long as it takes.

That is fine, as far as that goes. But towards the end of their illness the terminally ill are not fighting anymore. They are exhausted. They are in continual pain. Their bodies have been reduced to near-skeletons; they come to resemble hollowed-out concentration camp prisoners. They are ready to go. It is a time for acceptance. Time for kindness. And mercy. And for saying final goodbyes. There are forces larger than us at play. Phenomenon like cancer or ALS or Alzheimer’s or congestive heart failure or chronic pancreatitis or subdural bleeding kill us — my mother and stepmother have taught me as much. Death comes for us all, sooner or later. We are mortal; our bodies wear out. We die. Each of us has a birthday — Trudy’s was March 11, 1940; and sooner or later each of us will have a “deathday” — Trudy’s was October 6, 2020.

Trudy entered into a skilled nursing facility full of the elderly in early 2020 as the cancer advanced on her. Then the novel Coronoavirus pandemic hit in March and they locked down those places tightly to protect the vulnerable patient population from infection (even as Trudy eventually did contract the SARS-CoV-2 virus while there, unbelievably, while remaining asymptomatic). The policy was: absolutely no visitors. I never saw Trudy again.

Rest in peace, Trudy Ann Rideout. You had a good death — or at least as good a death as you could manage — following a good life. I hope I will be able to say as much. You have earned your eternal rest. You are home with God. You will be missed. Perhaps we will meet again in a better place.

Your Grateful Loving Stepson,

Richard

One Comment

Fritze Rodic

Your “In memoriam” to Trudy

was beautiful, sincere and heartfelt and I was very touch reading it.

Your mother in law

Fritze