Like a snail with its shell it feels as if I have carried them around on my back for decades.

My books. I own many of them. Too many?

From apartment to apartment, even while in college and early adulthood, I never threw away any book I enjoyed. They added up. A buddy laughingly likes to remind me of the time the Spanish-speaking day-laborer I hired to help me move sighed as he lifted another box full of books and muttered, “Más libros, más libros…” Those boxes were heavy. There were many of them. Books were like ¾ of all my earthly possessions.

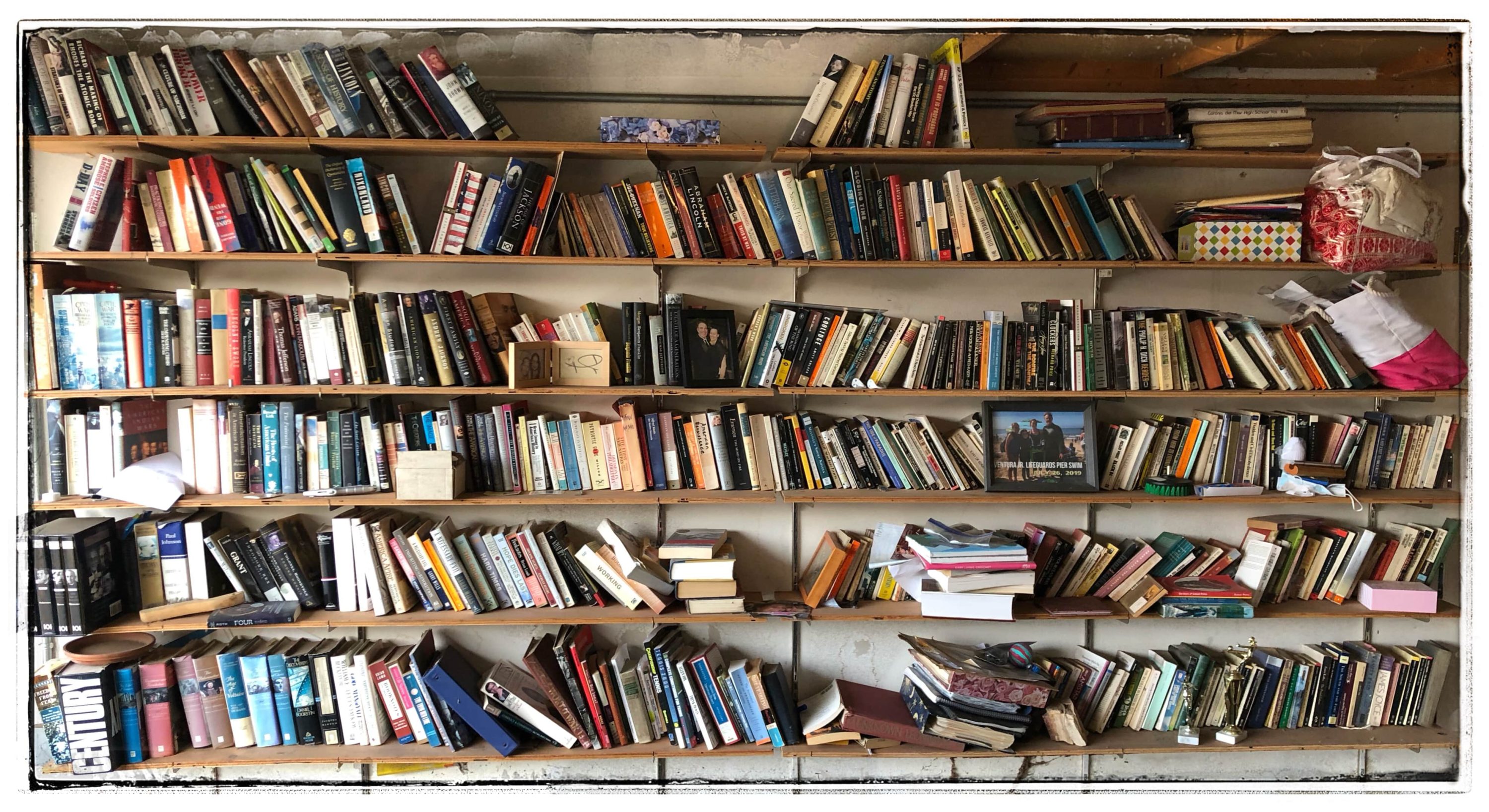

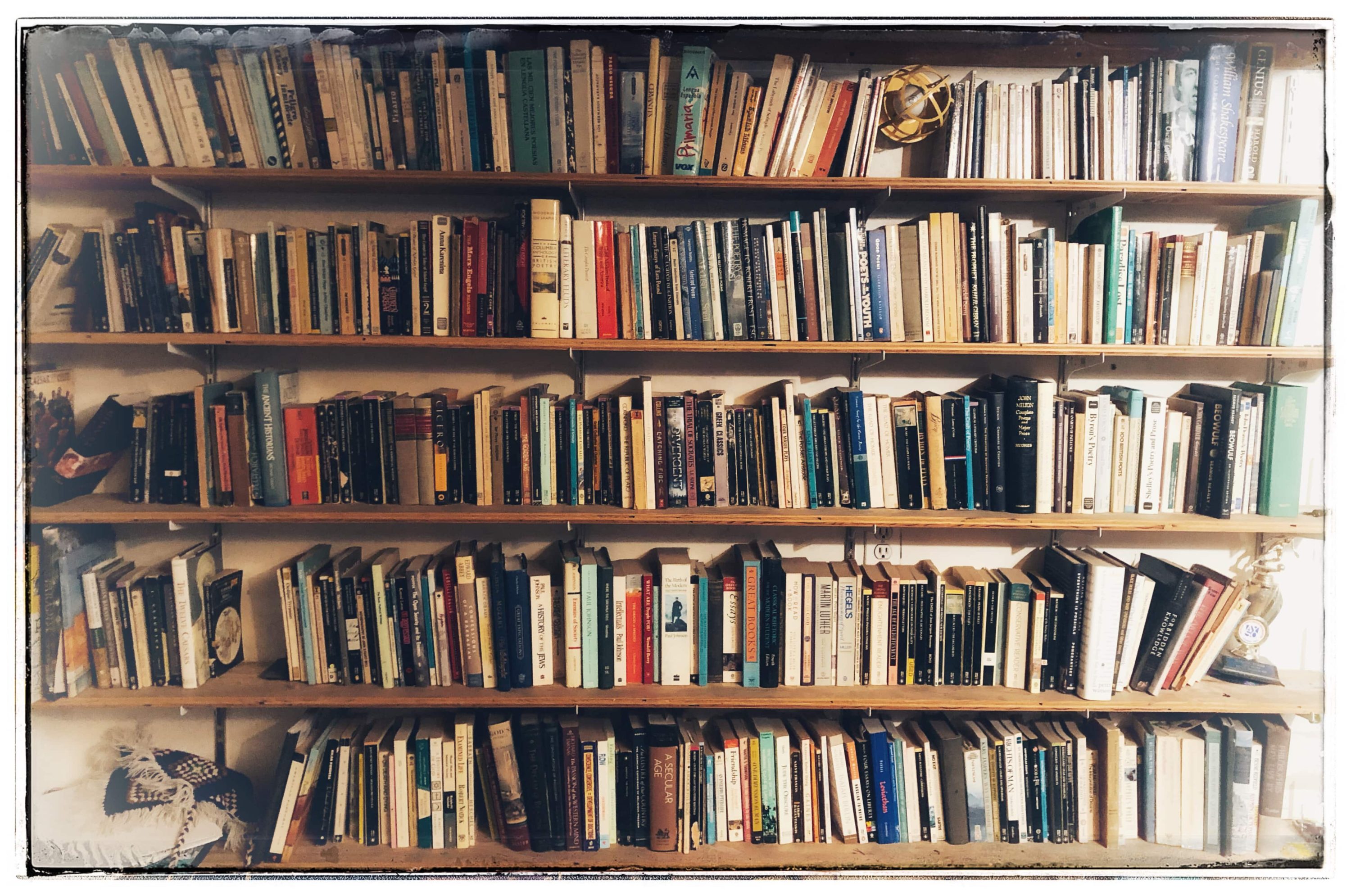

Truth be told, I knew I would never read most of them again. Sometimes, considering the amount of books I own, I had trouble finding some novel I wanted to read again. So I bought a new copy of the book when I could not find the old copy in my library, only to run across that old copy by accident soon after. In fact, this happens relatively often. Oops! There are just so many books. The custom bookshelves of my library cover one entire wall of my large 2.5 car garage, and the majority of another.

My wife has urged me to get rid of my library, or at least to thin it out. The books took up a lot of space. We could declutter our home and save space. It was a logical request.

Why did I resist?

Well, my books were a bit of an intellectual autobiography. I check out the libraries when I enter someone else’s home, looking for clues as to the character and tastes of the owner. Approval or disapproval comes soon afterward. The worst: they own no books at all, or next to no books. Almost as bad: to have high-quality, leather-bound books for display which the owner has not read and has no intention of ever reading. But most people own at least some books and you can learn a lot by examining a person’s library. So I wanted to preserve those books which have been so important in my intellectual and moral formation over my whole life. Am I my library? Is my library “me”? Pretty close. (You could say the same about my website.)

Also, I wanted to preserve my library intact for my daughters. I wanted these books available to them as they were growing up.

Often when I was growing up I would find myself bored bored bored. I would go into my parent’s library and peruse for hours. I read many books at home because I was bored and the books were there in our house. So I read them. It was that simple. Especially anything having to do with sex — I could sniff those out like a pig smelling out truffles. Any book my parents owned dealing even remotely with sex gained my attention.

I suppose bored teenagers nowadays go down the rabbit hole of TikTok or Instagram instead of reading books. How sad. I have often speculated that the relative decline in reading and literacy has much to do with all the electronic distractions young people have, compared to previous generations. Not that people back in the day, on average, were all that literate. There never was some golden age of literacy when most Americans read Thomas Hardy or Mark Twain on a regular basis; serious readers have always been, and currently are, a relatively narrow aristocracy. But literacy has gotten worse in the age of the smartphone and social media — with massivley popular videogames and nearly ubiquitous pornography — electronic distractions minor and major. Few Americans are serious readers of books nowadays: this is what I see as an English teacher. I started teaching in 1993 and it is almost 2022. While never great, things have gotten worse.

At any rate, for many years my daughters ignored my library. The books there were too old for them. The children’s literature — the Magic Treehouse or Percy Jackson series, or the saga of Harry Potter, or a litany of other John Newbery Medal winning books — those books remained near the upstairs rooms where my daughters live. They did not make it into my library. When the girls outgrew them, we gave those books away. Other families with young children could read and enjoy them.

But that has begun to change.

My oldest daughter, Julia, has emerged into the world of reading more mature literature.

In fact, I have noticed that some of the books in my library have migrated up to Julia’s library.

It gives me immense pleasure to see all this, although I will say nothing to Julia about it.

She is beginning to accumulate her own library. It is highly idiosyncratic — her library is a sort of intellectual biography, a listing of her personal interests and literary tastes. In her choice of books one begins to descry the contours and colors of her adult personality. Julia looks very familiar to me in her growing library. She reminds me of myself. It took almost 15 years, but Julia got there.

I am pleased.

Is Julia coming to resemble me in this way because we share DNA? Or because she grew up with me as a father? Or because Julia herself has an inquiring mind and likes to read? Is she the result of a book-ish family? Or is Julia a book-ish person by choice? All of the above?

Those are the age-old nature-vs-nurture questions which have no clear answer. But almost for sure it is both nature and nurture.

I remember back in 2009 asking a student of mine who I particularly esteemed, Ms. Hana Goldstone, how she became so smart and well-read. Hana was a standout student in high school, as well as an incredibly talented dancer who earned a full scholarship to college as a ballerina. She shrugged and responded to my question with the following: “My mother is a librarian. I come from a family of bookworms.” I was so impressed! I had become a father myself around that time, and right then and there I decided I wanted my own daughters to say something similar about our family.

And that process would seem to be well underway.

Ironically, last summer I purged a section of my library. Any book which could not justify its stay in my library would be donated to the Ventura County Public Library. My wife would have liked that almost all of them had been given away. In the end, I gave away maybe ¼ of my books. It took many hours to choose the books, box them up, and haul the boxes off to charity.

It is interesting which books I decided to jettison. Almost all of them were related to events of some temporary political phenomena in the past. It reminded me yet again how journalism is the most transient and least substantial of literature. Not too long after the pages of a newspaper turn yellow with age, the news articles in them soon become dated and fail to have any lasting value or interest. Does anyone care to read 98% of what a typical New York Times newspaper says on some Tuesday in 1982? It is the same with books with a similar focus on events from the past. What about the fall of the Soviet Union and its satellite states in the 1990s? What about Bill Clinton and the “new Democrats” as we approached the millennium? What about the state of the Internet in 2003? Almost all such books were donated. They did not pass the test of time; such books had become dated.

History fared better. Solid works of historiography, or those merely doing a powerful job of describing the drama of some historical moment, proved worth saving. More superficial readings of history, which bordered on journalism of the dime-store variety, got the boot.

The books I could almost never give away were the classics of literature. True enough, if a book was a “thriller” — if it was more “entertainment” than “education,” if the book lacked heft — I would get rid of it. But the pieces of literature which dealt powerfully with universal themes very much passed the test of time. I kept almost all such books.

I have heard some claim recently that we should read more books in our schools dealing with race and youth in America — but these calls are made mostly by political activists who want to read about and study identity politics — they want to read about themselves and their own preoccupations. Not everyone shares their politics, not by a longshot; not everyone is similarly invested, with their literary tastes. And whether this topic of racial identity will have the same relevance in twenty or fifty years is still in question. Will such a book pass the test of time and become a “classic”? Will such books engage universal themes which appeal to readers in other times and different places? Or will contemporary novels about identity politics in the early 21st century begin to look like political journalism — and so their relevance fades, as the political times change?

Only time will tell.

But most books do not pass the test of time. Few endure to become “classics.” Most books are deservedly forgotten. And it takes a few decades at least for a novel to become recognized as a “classic.”

So I am leery of most “popular” literature. Often they seem like cultural narcissism of the present time at play — “Look at me! Look at my time! This is who we are! See how we live!” Future readers may — or may not — find our present era and concerns to be of interest to them. I would seek to let the passage of time separate the wheat from the chaff when it comes to novels. So I tend to avoid the hurly burly of contemporary literature. I mostly stick with the classics; they mostly don’t let me down. There is a reason those books are classics.

And the books in my library which survived the purge of last summer were usually the “classics.”

They have passed the test of time.

And I wanted them to be available to my daughters as they grow up.

But after that I am ready to maybe get rid of many of the books remaining in my library — even the “classics.”

Many of these novels will be good solid books which I can appreciate. They are worthy of being read. Yet they did not engage me much. I remember reading novels in high school and college which I could appreciate were worth the read. They had value; I got it. I could see why the teacher/professor chose to include the book in the syllabus. But I did not especially enjoy them. It was not “my cup of tea.” I would not ever choose to read it again. Those sorts of books are going next.

Look at this random selection of books from my library —

Proust? Faulkner? Joyce? Balzac? Thackeray?

I do not regret reading them the first time. But I feel no compunction ever to read them again.

Out they will go!

Perchance I can find some young hungry reader to take possession of those “large, loose, baggy monsters”? Someone ambitious enough to attempt to wade through such complicated, convoluted narrative? I will wish them luck!

So if I get rid of books like those in ten years, I can get rid of some of my baggage. I can avoid being a laden snail carrying around a heavy shell. I can cut a leaner figure through life. I will hold on only to those possessions which I need. And I will keep only those books which really interest me and are most important. The rest will go. I don’t want to be like my dad who has hundreds and hundreds of middlebrow books nobody will ever read again. Purge, purge, purge!

To be honest, that might mean I hold on to quite a few books, nonetheless. But my library is becoming less important to me as I age, even as it is finally getting used by my daughters. I am on the downside of life, not the upside; I need to downsize, not upsize. This applies to work responsibilities and attention to current events, as much as to owning books and other material possessions. “Simplify, simplify, simplify!”

And in the future if I ever want to read something by Thackeray or Proust again, I can just buy another copy of that novel. Easy enough!

But some further purge of my library is years away. Right now I am fully engaged in raising my daughters and educating them — the great novels, the famous films, etc. I will make sure they are good with their sports teams: drive them to their unending string of soccer games, coach Julia’s tennis team, set up UTR matches and monitor her ranking, etc. I will also continue to tutor Julia in Spanish almost daily and try to travel overseas in Latin America with her, and continue the vocabulary lists and reading at night. My daughters are finally old enough to engage the world in earnest. Their still growing wings are fully formed and operational, and they are beginning to learn to fly fast and far! It is an exciting and exhausting time. But it will not last forever.

In a few years my daughters will be off to college. They will be launched! Time will pass by busily and quickly.

And as my daughters exit the house and begin their adult lives, I will start the process of retreating and retiring from life generally.

I will start to prepare to die.

It may take awhile. But the end is not in doubt.

Time to make changes.

It will be time to do less.

Time to focus on what is most important — and to disregard the rest.

“Our life is frittered away by detail. Simplify, simplify, simplify! I say, let your affairs be as two or three, and not a hundred or a thousand; instead of a million count half a dozen, and keep your accounts on your thumb-nail.”

Henry David Thoreau

Walden

2 Comments

Liam

Impressed to see Hegel’s Phenomenology and Charles Taylor’s “A Secular Age” in your library – two behemoths!

rjgeib

Two books which at my advanced age I might never read again!