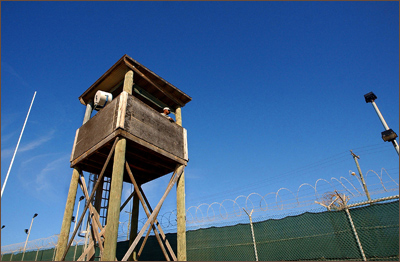

GUANTANAMO BAY DETENTION CENTER

Reasonable measure to secure our country? Or overreaction and judicial “black hole”?

ON TERRORISM AND CIVIL RIGHTS:

Today is the sixth anniversary of the terror attacks on September 11th, 2001. It is time to opine on a topic increasingly on my mind these past several months: civil rights in the context of the age of spectacular terrorist attacks.

For several years I have struggled to make up my mind about the detention centers in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, where the US Government has held thousands of suspected terrorists swept off the battlefields of Afghanistan and elsewhere. This has been a keystone policy of President Bush’s “War on Terror,” whereupon America is supposedly a safer and more secure place than it was pre-September 11th, 2001.

In the aftermath of those attacks, President Bush and his lieutenants have vigorously – some say imperiously – moved to attack terrorist targets whenever and wherever they could be found. Bush invaded Afghanistan, and then later Iraq. Bush has had the CIA kidnap terrorist suspects (an “extraordinary rendition”) from Europe and have them taken to secret CIA facilities – and many others corralled into Guantanamo Bay, Cuba and declared “enemy combatants” with little legal recourse. The government under Bush’s stewardship has secretly monitored domestic phone conversations by use of the NSA without court warrant. Congress easily passed various versions of a “Patriot Act” to give government more power to investigate possible terrorism.

Much of this, I have to admit, is appropriate under the circumstances. It is the President’s job as chief executive of the government to ensure that the people are safe from mass attack. That office worker on the northern side of the North Tower of the World Trade Center on the 95th floor on September 11th, who watched with horror and a jet airliner headed for his window at 500 mph, could rightly blame the President, the FBI, and the CIA for not foiling the al-Qaeda operation that was to take her life, and well as the lives of several thousand others. The President of the United States has truly awesome power at his or her command, and we really want him or her to have those powers. Too little power in government is as bad, in my opinion, as too much power. There are many countries around the world today that suffer from chaos and disorder without any real authority in the country being able to guarantee the safety of its citizens.

There has always been a sliding scale where freedom in the United States is restricted in the name of collective security, and historians have long argued if what the president did in this era or that was “reasonable” and “appropriate,” under the circumstances. Historians seem to conclude that the Alien and Sedition Acts of the 1790s were a clumsy Federalist overreaction to supposed French radicalism that did not significantly improve United States security and damaged a still nascent American democracy. On the other hand, historians have concluded that the massive civil rights clampdowns orchestrated by Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War were appropriate in the context of that crisis. Lincoln imprisoned hundreds without trial and ignored Supreme Court decisions ordering him to produce suspects for trial, declaring to critics the following:

Are all the laws but one [the right to habeas corpus] to go unexecuted, and the government itself…go to pieces, lest that one be violated?

The Constitution, and the protections of our civil rights therein, is not inviolate; the rights we enjoy are to be tempered by reasonable needs of the government to protect American citizens. As the legal dictum claims: “The Constitution is not a suicide pact.” I sometimes hear civil libertarians warn of “creeping fascism” by the Bush Administration and have to shake my head. In six years since the September 11th attacks, how many American citizens have been arrested without trial? How many of us have endured an FBI interrogation about our links to terrorism? How many of us have been imprisoned for penning an antagonistic letter on President Bush to the local newspaper? Groups like Human Rights Watch make civil rights seem the most important (or almost the only important!) consideration in society. The American Civil Liberties Union and its ilk speak about civil liberties the way fundamentalist Christians talk about virginity: a precious “all or nothing” proposition of enormous value, once desecrated never again pristine.

Laws are to serve society and citizens, and they can change with the needs and times. Most reasonable persons recognize it is the job of the government to keep its citizens safe in their homes and work places, and when the government claims its needs certain abilities to do this I listen to them. “Freedom for the wolves means death for the sheep,” Isaiah Berlin famously asserted. During the six years since the epochal attacks in New York and Washington D.C., there have been no terror attacks in the United States – and it is not for lack of trying by Islamist terrorists. Nobody in America has had to sit in their office again and watch in terror as the appearance of a jetliner (or other instrument of death) outside their window signaled their fiery, impending demise.

But here is the rub: what is reasonable for the government to be able to do in our name, and what is unreasonable and unproductive? What is the result of overreach and heavy-handedness, so common in so clumsy a tool as government? The internment of Japanese-Americans during WWII, for example, is almost universally thought of a giant error born out of hysteria which did not help the war effort or make America more secure. If Lincoln suspending habeas corpus seems appropriate in the context of the Civil War, there are many or more examples of inappropriate government action in wartime. Why in the world, for example, did the Nixon Administration need to tap Coretta King’s or John Lennon’s phones and read their mail?

But let’s move to the point: What about George Bush and his “War Against Terror” in the early 21st century?

The more I think about it, the more I conclude that the Guantanamo camps should be closed down. I am unwilling to give to the President the power to hold suspects indefinitely without any kind of legal hearing for detainees. I am also made very nervous by the NSA listening in on domestic phone calls without a court warrant. It seems President Bush, in the crisis of 9/11, has come to the conclusion that there is a permanent state of extreme emergency that demands that we just trust him to make all these decisions without consulting courts or working within a legal framework outside of the Executive Branch.

For example, there already exists a FISA court where the government can get warrants in complete secrecy. Why does the President not operate in the framework of this court? Congress must have oversight powers with the FBI and warrantless searches, and a judge should be involved – or at the very least notified afterwards, if it be an emergency – when the NSA monitors internal communications. And can the President reasonably assume that he can stick terrorist suspects in detention centers indefinitely without any legal redress whatsoever? Do we have to rely completely on the Executive Branch as to whether a suspected terrorist belongs in Guantanamo? Are we to believe that no innocents were scooped up with the guilty and brought to Cuba by mistake? Is there any system that forces the government to explains its case, and gives suspects an opportunity to give their side of the story?

President Bush paints a picture of himself as a forceful and strong leader who does what he has to in the name of keeping America safe. He claims to be untroubled by his many critics. Bush says he is “the decider” and will do whatever he feels he need to, despite Congress or the Supreme Court. And in crisis times the government has always acceded, if temporarily, to the president. But in reality the people of the United States are the “deciders,” and any policy that the President of the United States enacts in the name of the people will undergo a referendum in the next election. As such, President Bush was, in effect, fired in the 2006 mid-term elections. In 2008, even if he could run, Bush would not be elected dogcatcher. The vast majority of the country disapproves of his administration, especially his disastrous War in Iraq. After 2008, federal policy with regards to civil rights will change, no matter what Bush thinks.

But it will most likely not change much, in the context of the post-9/11 world. Many now think George Bush a bull in a china shop who is to reckless in his use of power at home and overseas. Personally, I believe George Bush does more damage than good to American democracy with his policies. On the other hand, President Clinton in the 1990s was clearly too lax in his use of power to combat al Qaeda, and any American politician who lets terrorists coalesce in peace and plan spectacular attacks against the United States will be even more unpopular than President Bush is now. The Scylla of being too soft and the Charbydis of too harsh on terrorism.

Even as a bitter critic of him, I sometimes cringe at the cheap shots many take at George Bush. You think it is easy being President of the United States? But even under so much pressure with problems so big and complex, Bush has shown little of that most precious and important political commodities: wisdom, good judgment, a sense of the bigger picture, the good of the country. In the 2000 election during peace and prosperity I voted for a president who had managed well a major league baseball team and seemed a good lightweight leader to run the ship of state which needed little guiding. But after the crisis of 9/11 I got an obdurate and shortsighted simpleton who was in over his head in trying to navigate the nation through a crisis. The irony!

President Bush lost me with his war in Iraq. And I am increasingly against his civil rights policies with regards to terrorism. Don’t get me wrong. I don’t worry about “Bush police state” we supposedly now live in or make a fetish over the civil rights of terrorists, as do some. If the man has links to al-Qaeda or Islamism, investigate and/or arrest him. Monitor their communications, and bring the full weight of the police or military against terrorist threats. For the terrorist wolf hunting for civilian sheep in America, bring the full weight and hard edge of government power against him. But bring the courts into it, and let Congress know exactly what is happening. Explain your action to the voters. If the laws are too lax with regards to terrorists, change them or politic for their change. The vast majority of Americans will support this. But do it within the American system of checks and balances. George Bush is President, not King.

Again, do not mistake me for one of those weepy-eyed professional civil rights activists. Take someone like Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, for example, who currently resides at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. He is a deadly threat, a religious fanatic, and a man with many political murders to his name. I don’t much care about his “human rights.” Take him outside and put a .45 slug in his brain, for all I care. But that is an extreme example. And this water-boarding, sleep-deprivation, and “stress positioning” is so weasely. Convict him, execute him, but don’t just hold and play and pester with him. For the majority of those held at Guantanamo of less renown than Khalid Sheikh Mohammad the situation is less clear cut. “We think he is guilty as sin but we don’t have any real proof, and so let’s just keep him here where he can do no harm.” Warehousing Islamist terror suspects at Guantanamo indefinitely without charging, trying, or executing them is no long-term solution.

But then there is this example: Taliban veteran Abdullah Mehsud was captured by U.S.-allied Afghan forces in northern Afghanistan in December 2001, but then was released from the Guantanamo detention camps in March 2004. Mehsud immediately returned to fetid Southwest Asia and took up arms again, leading local and foreign Islamist militants in Pakistan’s lawless South Wazir region. He killed as many as he could and did as much damage as possible until Pakistani police finally corned him on July 24, 2007 whereupon Mehsud blew himself up with a grenade rather than be apprehended. Good riddance! But did the U.S. Government err in letting him out of Guantanamo in the first place?

The question, as I see it, comes down to this: does a terrorist suspect like Abdullah Mehsud or Sheikh Mohammad deserve a “fair trial.” It is custom in the United States to be considered innocent until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt, and that five guilty persons might go free so that one innocent person not be found guilty unjustly. That puts a heavy burden on the state. The question is this: Can America afford to give full legal protections to all terror suspects and let several Abdullah Mehsuds go free after trial in the name of protecting one innocent who is unjustly found guilty? With as deadly and opportunistic an enemy as al Quaeda, do we give its members full Constitutional protections?

I find myself deeply conflicted on that question.

This discussion on civil rights has all too often popularly been a “we need the power to protect American citizens” on the one side, and “we need to protect civil rights” on the other. A better question might be: To what extent can we afford to give Islamist terror suspects their full civil rights while still pursuing an effective anti-terrorist policy. To what extent can we follow legal channels in places like Pakistan or Yemen where there is no law? How much can you fight vicious and implacable fanatics without becoming one yourself? And if you don’t become one yourself, can you expect to win?

There are plenty of examples of overeducated peaceniks who are kidnapped and/or victims of rape, and who fail to overwhelm or escape from their attackers when offered that opportunity because of a lack of that “dog eat dog” sense of survival; after having missed their opportunity, these victims often were killed. “Turn-the-other-cheek pacifism,” George Orwell observed in 1941, “only flourishes among the more prosperous classes, or among workers who have in some way escaped from their own class. . . . To abjure violence it is necessary to have no experience of it.” I would not have us be too “civilized” to survive in a violent, chaotic world. (Leave that danger to the Europeans.)

But where is the line between fighting fire with fire and being strong enough to survive, and descending to a level little different than one’s foes. As Nietzsche claimed, “He who fights with monsters might take care lest he thereby become a monster.” It was always the danger in the Cold War that in rightfully standing up to Joe Stalin and his successors the United States might become little different than an authoritarian regime. But you don’t get down in the mud to fight with a rabid dog who likes it down there without getting muddy yourself. Neither can you afford to ignore the dangerous dog. What to do?

Why is it that so often the difficult questions are those nobody wants to ask? Or answer? I never hear ACLU lawyers wanting to talk about the powers the government should have to keep its citizens safe – the powers we all want the government to have. And we rarely hear law enforcement officials talking about the civil rights the law demands they respect. Fair enough – the system makes these two interest enemies.

But why do so few thoughtful commentators lock in on that immensely complicated gray area of exactly what powers should the NSA, FBI, CIA, and US military have in fighting Islamist terror worldwide, and how much oversight should courts and Congress have in those efforts? How much, really, does the government need? Why? Where? How much is a clumsy overreaction and abuse of power and civil rights?

On these questions I would be most attentive to a complex, candid discussion. I am just an average citizen and possess no special expertise in legal or terrorist affairs; I would welcome expert testimony. So far there is much posturing and speechifying to defend entrenched positions on terrorism and civil rights, it seems to me, and too little honest discussion on a vitally important subject.

Too little of that most rare and blessed virtue, wisdom.

THE WORLD IS RID OF ABDULLAH MEHSUD:

“It appears he [Mehsud] did not want to be captured alive.”

Pakistan Interior ministry spokesman Brigadier Javed Cheema

One Comment

Vic Mann

Richard Geib, I would like to see you talk about your opinions on Lyndon LaRouche. LaRouche often criticizes Bush, but I see him as a cult leader and far worse than Bush!