“No man stands so tall as when he stoops to help a child.”

Abraham Lincoln

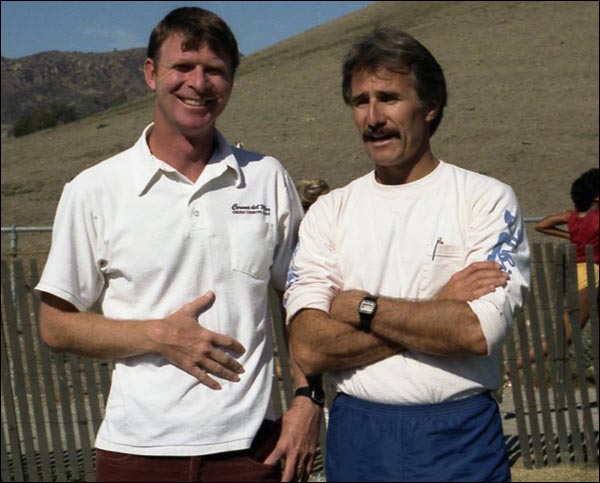

Coaches Jim Tomlin and Bill Sumner

“What counts in life is not the mere fact that we have lived. It is what difference we have made to the lives of others that will determine the significance of the life we lead.”

Nelson Mandela

Grandiose words from Mandela. A powerful sentiment. Moving.

But are they true?

Do we really want “significance” in our lives? Do I?

I think long and deep about this as I near the completion of my twentieth year of teaching.

Have I spent the best, most productive part of my professional life well? Thousands and thousands of hours as a classroom teacher? Three different schools in both the public and private systems? My best energies and working life from the age of 25 through 45? Do I have regrets?

Richard, the beginning teacher.

On the whole, no.

I have mostly enjoyed my students year in and year out, and to be paid money to teach “Romeo and Juliet” or the Civil War to young people – well, I would almost do that for free! I have been able to be extremely creative in my job, and the marriage of what I do for fun (read, write; think) and what I do at work (get students to read, write; get them to think) has been a joy. (This central intellectual focus of teaching has outweighed the significant negatives of that job: the bureaucracy, the mediocrity, the slop.)

It is no small reward for two decades of teaching that I look on Facebook and see hundreds of students who I still stay in touch with and have warm feelings towards. They were in my class as a tender age, and now they are young adults — graduating from university, entering into careers, getting married, and even having their own children. This very “human” dividend of mutual affection between teacher and student is, I have found, one of the rich rewards of being a teacher. I can remember decades later very vivid moments that illuminated some aspect of their character or other. It is all the richer, I realize, because there are plenty of teachers who are disliked and even despised by their former students. (The first rule of teaching, I suspect, is the following: “First, if at all possible, do no harm.”)

There is one example that prominently stands out in my mind: a high school freshman entered into my Honors English class, and although I very much liked him I finally gave him an “F” for not turning in classwork. (I remember enjoying the student personally and admiring his intellectual curiosity, and I barely remember giving him that failing grade.) But then by his junior year he was in my Advanced Placement United States History, and while he was the same kid in his lively intelligence and wit he had grown more responsible in playing the “game” of school. He earned an “A” in that class, a highest possible “5” on the end of the year exam, and was well on his way to UC Berkeley and then eventually Georgetown Law School. I would have lunch with him and other students on school days, and they would come to my house to welcome my first daughter into the world. I had this same positive connection with many other students. The minutes on the clock they would speed by in classes where student and teacher got along so well. It hit the “sweet spot” in the gut. One knew one was participating in something positive and good.

His mother claims the lion’s share of his academic success was due to me and my influence, although I think it has much more to do with her son than with me. But as a way of saying thank you she promised to come to my house and deliver handmade gifts to my daughters every Christmas Eve until they turned 18 years of age in what is a singularly generous gesture. I remind myself of this unusual specific because it comes to mind when I think that what I have done lacks merit. I can brag to my family and friends that someone noticed.

She comes to my house to deliver them personally on December 24th. My mother-in-law for all the world cannot understand why this woman would knock on our door on Christmas Eve with presents in hand.

Now I have my flaws and weaknesses as a teacher, which I know all too well. But overall teaching has been a good fit. Only a few of my friends and acquaintances really “fit” their jobs, and fewer still seem to really enjoy it. Most of my friends seem to do a job for the money, and that they have various professional responsibilities – and they don’t think much beyond that. They just do their job. The schema seems to be this: There is their work life which they do for money. Then there is their home life which they do for pleasure. Maybe they like certain aspects of their job, but mostly it is labor done for money. But work should be something you enjoy doing and find passion and purpose in – a “calling,” a vocation. Something you would almost do for free.

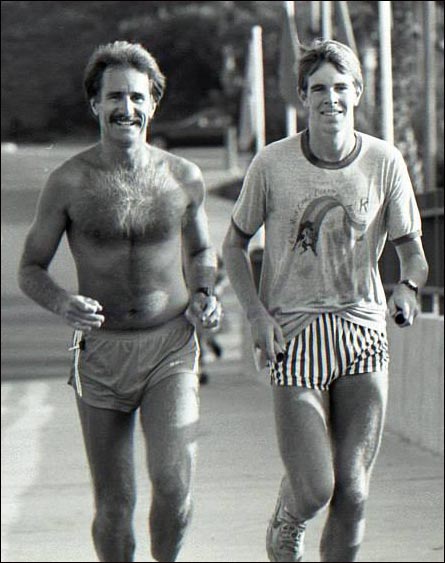

Brian (left) and Dean (right) when they were still athletes, not yet coaches.

And this is what brings me back to Mr. Bill Sumner, Mr. Brian Hunsacker, and Mr. Dean West. They all chose to coach track and cross country at Corona del Mar High School in the early and mid- 1980s when I was on their teams. None of them made much money doing it, I imagine. They did it, I suspect, from their love of the sport. (I purposely direct my comments away from the inimitable Jim Tomlin , as he was also a teacher and so better paid.) These men were my coaches.

I benefitted hugely from their time and energies in a formative time of my life. And it is not really about what I learned about training and competing in running races of various kinds and distances. It is simply that they spent time with me, talked to me, traveled on buses with me. It was that through their actions they said “I care.” They weren’t late to practice. They showed up to all track meets and were often the last ones to go home at night. We trained during the summer and during vacations. They mentored. I learned discipline. I was so much the better for their involvement in my life. In a delicate time of life they provided firm support – a guiding hand pointing the way forward. Adolescents need direction and help from interested adults (coaches, teachers, whoever) who are NOT their parents. They have already heard what their parents have to say. They want (and need) further input.

And this brings me to Bill Sumner.

I still remember like it was yesterday at the end of my junior year in 1984 when they introduced Bill as the new cross country coach and how he started talking and talking and talking about all the championships we were going to win, etc. etc. How Bill could talk! He would get a person so pumped up that the adrenaline would flow and excitement seemed to course through the room. He developed talent primarily by building up people; his charisma was evocative because it helped others to believe in themselves. In short, his enthusiasm was infectious. I remember sitting around after practice in the locker room listening to Bill talk about growing up poor in the barrio and his Vietnam military service. I remember meeting his charming and attractive girlfriend. The man impressed me on a variety of fronts.

High school running coach,

Mr. Bill Sumner.

One encounter particularly stays with me: I remember coming across Bill working at night in a local convenience store, presumably to help make ends meet. Bill sold insurance as a day job, and I wondered that he would need to work at night in a second job. My friend Phil and I went to that store once just to talk with Bill one evening. After a day of working two jobs I imagine the last thing an exhausted Bill must have wanted was two high school kids taking up his precious time and energy. But he gave us his undivided attention and was as courteous and enthusiastic as ever. How much I appreciate that now! We liked/admired/respected Bill so much we travelled to this convenience store in our free time just to be near him. (I am a bit amazed at that, in retrospect.)

But why in the world would someone like Bill have to work two jobs to make ends meet? (If that is indeed what was happening.) Why would a man who gave so much and had so much to offer have to endure a twelve hour workday? And then why do so many obvious scoundrels make more money than they know what to do with? Some 29 years after the fact, those questions haunt me more than ever. My other coach Dean West, always a bit of a hippy, took his VW van and moved up to Oregon to do I am not sure what for a living. Coach Brian Hunsaker, as far I can discern, went to operate his father’s turkey business. The truth of the matter seems to be this: the American capitalist system rewards or ignores people in relation to the marketability of the skills they bring to the marketplace. A high school coach is compensated little, unless his clients (athletes) are wealthy. A worker that deals with wealth becomes wealthy.

Bill Sumner is currently a central organizing figure in the Orange County running scene. He has been the Corona del Mar High School cross country coach ever since he took over the team in my senior year. When I finally found him on Facebook, I saw that he had almost the same exact number of “friends” as I did at the time: 1,000. I strongly suspect there and hundreds or even thousands of people who idolize him. I am sure he could wallpaper his house with “thank you” letters from athletes he has coached. I am sure, were Bill to pass away, there would be legions at his funeral. I would be there.

Has Bill’s life been “significant”? I would definitely say so. The man is a hero, in my eyes.

And I hope he makes good money and does not scramble to pay his bills. I hope his retirement is comfortable. Bill entirely deserves it.

And this is where I come to what I have really been disappointed in with my country.

I walk around Balboa Island on the sidewalk there with my dad and peer into people’s houses, and what do I see everywhere: sports and alcohol. Getting a good buzz and being entertained. The writer Michael Chrichton once stated, “In the past, people wanted to be saved, or improved, or freed, or educated. But now they want to be entertained.” Hollywood. Silicon Valley. Wall Street. “How is the stock market doing?” “How much money did the latest blockbuster movie earn?” Money and status. The new technology stock and its impending sale. Real estate and housing trends. The Mercedes Benz automobile. USC football and wine and beer. Celebrities and celebrity gossip – celebrities as the aristocrats of our civilization. For some reason we really do care how they live, what they do. Enormous amount of time and effort go into following their lives.

And even low to mid- level employees in entertainment or financial industries make six figure salaries, since their jobs revolve around others who have wealth. While Bill Sumner was working two jobs, I think, to make ends meet.

I suppose it has always been like this. The mad scramble to make money and seem better off than your neighbor. The competition for status in the eyes of others.

But this essay is not really about Bill Sumner, but about me.

Richard, Maria, Julia, and Elizabeth.

I begin to approach the downslope of my career after twenty years, and I look out at what I might want to do next. A second career after teaching? But nothing out there in the world of selling and buying looks very appealing. Nothing in my country, in fact, looks very interesting.

America talks about values and ideas or whatnot, but page after page in the newspaper is Target ads, used cars for sale, and “special deals” and coupons for cutting out. Our priorities are writ large in how much paper is devoted to commerce versus reporting in the newspaper. I held so much hope for the Internet as a medium for social discourse and human sharing back in 1996, but so much of commercial America moved online eventually to push to crowd out us early adopters. My personal webpage is still up 18 years later, but the Internet today is dominated by social media, digital commerce, streaming video, and pornography. America in person seems to have replicated itself online. Is this not sad?

I was hoping for an Internet fashioned after St. Augustine’s Confessions or Montaigne’s Essays. We shall see. The Internet is a big place.

And what do I want as I approach middle age? “Midway through our life’s journey, I found myself in dark woods, the right road lost,” Dante described the mid-life crisis. What is my “right road”?

I want to get my daughters raised healthily and well and accepted into good colleges. I want to pay for tennis lessons and soccer teams, and then pay for theirs and my food, clothes, housing, education, and health care. I will drive them everywhere they need to go without complaint. I want to spend all the intense hours talking and guiding them through childhood and adolescence, reading Jane Austen novels with them and taking historical car trips through New England. I want them well launched and accepted to prestigious universities. I want them to have strong bodies, resilient characters, and confident demeanors. I want them to be kind and gentle. I want them to be the best aspects of themselves that they can choose to embrace and be.

And, in short, I will do my very best to make this happen. I will dedicate my best hours for the next fifteen or so years to doing what I have been doing for the last seven years: raising my daughters as well as I can. To have a happy family.

After that I draw a blank.

Richard, veteran teacher, God help him.

For some reason, I suspect I will not live much past sixty. Maybe it would be a self-fulfilling prophesy, as I don’t see much to live for after that. I might just be ready to take my coat and leave the party at that point. Julia, for some reason, often expresses fear that I will die. Eerily, it is as if she senses something. She bursts into tears. I sense she might be right. I am partly ready to go.

But nothing terrifies me more than the idea that I might die before my daughters come of age. I have seen too many young women without a strong male presence to guide/support/protect them and how often they are victimized. It is like predators can sense they are vulnerable.

And then I remind myself that I have benefitted hugely from having a loving and involved father all my adult life. To lose a father even at 18 years of age is a heavy life blow to the gut; I lost my mother at age 26, and it would have a much harder if I had been only 18. We need our fathers not only in earliest youth, although maybe we need them most then. I don’t forgo my paternal responsibilities when my daughters turn eighteen.

I peer into the misty future, and what do I see? Maria and I in our next stage of life? Become international teachers and move to Costa Rica? What does Richard do at 60 years of age?

I have no idea.

Has my life been “significant”? I don’t know. I have positively influenced some. But I don’t know. I wonder.

But I do know that Bill Sumner is incredibly significant, by Nelson Mandela’s measure. And it frustrates me that America has not seen fit to compensate him like it has certain others of a lesser ilk – that Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt, the Kardashian sisters, Lebron James, FOX News, MSNBC, and many others have hogged all the attention.

But Bill Sumner, Dean West, Brian Hunsaker, and Jim Tomlin have something those others don’t: my absolute respect. And I have fashioned my adult life in a similar vein, giving truth to the claim that “imitation is the most sincere form of flattery.”

None of us succeeds without help, and most of us who rise up we find ourselves standing on the shoulders of the giants who came before us.

I just wish America cared more about these “giants.” I wished we cared more about character and building potential rather than making money any way possible and attracting attention with meretricious nonsense.

I was mainly indifferent to the Roman Catholicism of my upbringing. But I was enthralled by classical learning – by Greek philosophy, Romantic poetry, 19th century Russian novels, and everything in history. I thought them worth fighting and dying for. If I ever had a spiritual home, it was the Great Books program of Mortimer Adler and Robert Maynard Hutchins at the University of Chicago. The key to the good life, I thought, was to feed the soul with elegant language, beautiful music, and powerful ideas. It was the example of the inspiring lives of those who went beforehand. I tried to devote my life to this.

And I still believe in those things.

But almost nobody I knew cared much about books or ideas in my day-to-day life. They cared about USC Trojan football or the LA Dodgers, the Star Wars movies or TV show of the season, or alcohol of various flavors and getting high. Peer groups and social media.

And making money. Always making more money.

(Maybe I just hung around the wrong people. Or maybe I didn’t look closely enough at the people around me.)

America would like to claim that it is “family friendly.” Very often, it seems to me, it is not. Often it seems like a place for selfish fifteen year olds with ADHD.

We Americans seem to want wealth, not “significance.” (Or maybe they think that weath automatically equals significance?) Many just want a job, any job. (I can hardly blame them, when so many have so few skills or options, and little money.) But in a highly materialistic America, Mandela’s credo of making a difference to others seems much less important than making money. Making a difference comes in a distant second to making money.

Maybe in an America in 2014 that is economically stressed we are more concerned with taking care of the money equation, and everything else be damned.

But I feel more than a bit disillusioned.

There was the promise of America held up to me when I was a child. Then there is the America I see around me as an adult. The comparison is not favorable.

In so many ways the California and United States of the 1970s and 1980s appear to me to be the halcyon days, in retrospect.

Then: Relatively inexpensive housing, quality public schools, cheap but world class higher education, a vibrant middle class, more equality.

Now: Expensive housing, expensive health care, struggling public schools, expensive higher education, an endangered middle class, inequality.

Alas, America! Alas, my daughters!

February 2014

California in the 1970s and 1980s; the California Dream Since Lost.