I returned home last night from my weekly men’s tennis night to find my younger daughter exhausted and overwrought.

Her eyes were ringed red with fatigue, and she sat down at the kitchen table and burst out crying. It took me by surprise. I wondered if something bad had happened to my daughter that day, but then I quickly surmised this was an overtired 12-year old “tween” very possibly with hormones running amok.

I grabbed her hands and told her I loved her. I got her older sister and mother to tell her things they admired about her. After a few minutes of unconditional love and support, I wondered how I could get her upstairs and asleep as soon as possible. She would feel better the next morning. Sleep was what she needed, I strongly suspected. She was inconsolable. Tears and more tears. Words and reason would not work with her. Only sleep would help, I concluded.

It was incredibly ironic. Just an hour earlier I had just been commiserating with my tennis buddy Prashant who has two young children at home – one two years old and another four and a half years old. I asked him if parenting stressed him out. Prashant shook his head clearly in the affirmative and explained that he really struggled with bedtime. His children would refuse to go to sleep, and they didn’t want him to leave their bedrooms. It would take hours, Prashant told me, and the process was full of stress and anxiety. “There is nothing harder in my parenting than the bedtime struggles.” he explained while I listened. “My kids as they are going to sleep tell me to come check on them in five minutes, and then they wake up an hour later, get out of bed, and come crying to me that I didn’t come check on them. Bedtime sometimes lasts the entire evening!” I totally understood.

I told Prashant that for me, ten years ahead of him as a parent, the bedtime struggles had also been lengthy and frustrating. My older daughter was a particularly difficult baby, suffering from raging colic. She would scream bloody murderer if I ever tried to leave her room before sleep had rendered her oblivious. It took an hour or two, or maybe even three – every night!. So I finally decided just to roll with it. I spent the next seven or so years reading books to my older daughter at bedtime – a long list of children’s literature from the Magic Treehouse to the Harry Potter series to Where the Red Fern Grows to Wonder to The Wizard of Oz to Little House on the Prairie to whatever else I could get my hands on. Day after day. Month after month. Year after year. It must have been hundreds and hundreds of books I ended up reading to my daughter, over thousands and thousands of hours. I simply read books to her until she fell fast asleep.

It often took awhile. Usually I was there for an hour or two. But time was on my side, I learned, and all that was required was patience. Sooner or later, my daughters would fall asleep. Sometimes I did too, for a few minutes. But not usually.

My father hinted that I was spoiling my kids in their earlier years, by putting myself at their full disposal. He advised, “Let her put herself to sleep without your help. Let her cry it out alone in your room!” But I am glad to have spent all those hours reading all those books at bedtime. It wasn’t really about the books in the end; it was about father-daughter time. Bonding firmly with your child. Cementing the bonds of parent-child love: an attachment which cannot be undone. “Give me a boy for seven yeas and I will give you the man,” the Jesuit educators used to promise. Indeed.

When my younger daughter came along three years later, I did the same bedtime routine with her. Not because she demanded it like her older sister did, but because I wanted to give my daughters equal treatment. I wanted her to have the same daddy-daughter experience. So I spent some seven years doing the same for her. By then I had learned patience and perseverance. I was trained. I kept the hours around bedtime fully open for my daughters. It would take as long as it would take. I wasn’t looking at my watch anymore. I was good-to-go.

I still remember at the beginning how sort of horrified I was that bedtime routines could cost me two hours every evening. “I have work to do! I want some time to myself! It’s been a long day for me, too! Go to sleep already, daughter!” (Years later I read the Go the Fuck to Sleep “adult children’s book” and was totally sympathetic.) Parenthood was quite the shock to my system in those early years: to become a parent for me meant I would lead a very different lifestyle than I had before and there would be sacrifices. There would be opportunity costs in terms of time, money, and attention. I was willing to pay. It took some time, but I came to embrace this lifestyle totally.

A decade later, I think it was totally worth it. Nowadays my older daughter (15-years old) wants her privacy in her own room as much as she demanded that I be there until she fell completely asleep as a toddler. A good parent makes themselves increasingly unnecessary as children grow older, gain confidence, and find their own footing. Troubled children, in contrast, never seem to outgrow their parents.

But I am still in the thick of it, as last night’s encounter with my overtired, overwrought 12-year old daughter shows. She still needs me. At least sometimes.

So I was trying to help her relax and go to sleep yesterday evening. We were lying on her bed. I rubbed her back. It was dark and quiet. She put her arm around me and started to settle down. She told me the real reason for her touchiness: she had smiled at a boy she had a crush on, and he had not smiled back at her. She later admitted that she was wearing a mask at the time, and so he could not have seen the smile or even known who it was – “The emotional rollercoaster – the sharp ups and downs – of being a sixth-grade girl. It is not easy!” I thought to myself. My daughter’s overwhelmed brain began to calm down finally as the release of sleep approached. But I was there in the dark, like in the past, wondering how long it would take her to finally fall asleep so I could get up and leave. “Is she soundly asleep yet? Can I get up and leave without waking her up? Should I try? Or wait a few more minutes?” I monitored her breathing for signs of deep sleep. When I finally got up, she muttered in a sleepy voice, “Good night.” She let me leave.

The entire process took about an hour and twenty minutes.

I waited patiently.

I thought I handled my daughter’s mini-crisis well. But my reaction when I saw my daughter dissolve into tears at the kitchen table was instant and instinctual. I knew what to do: comfort her, with physical touch and reassurance – make her feel loved, and get her to relax and go to sleep.

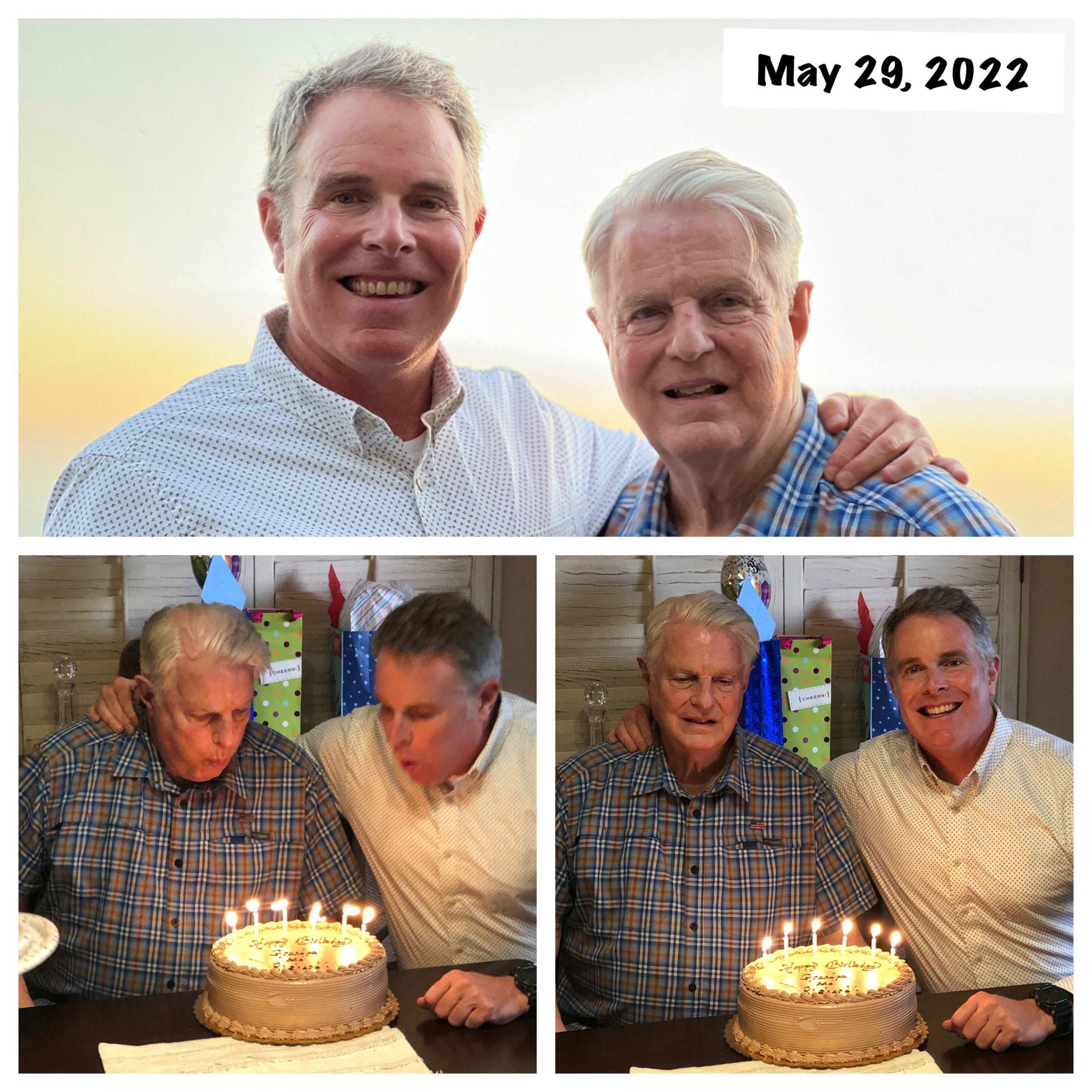

As I lay there later in the dark waiting for her to let go of the final strands of wakefulness, I realized why. It was because of my mom. She was worth a million dollars in situations like that. I acted towards my daughter in the same way my mom acted with me when I was a kid. I knew the routine because I had lived it. It did not matter if four decades had passed since then.

And in that moment last night, lying next to my daughter, I felt closer to my mom than I had in some time. As her death recedes further and further into the past, I often struggle to feel my mother’s presence. But not last night. Lying there, I felt her clearly.

“Hey, Margaret Mary! Thank you for being a great mother,” I thought to myself. “I try to pay you back in how I treat my own daughters.”

This is how one generation positively affects successive ones – how the emotional, educational, and financial support of the past all make a difference in the lives of children.

Or fails to.

“What is there about fire that’s so lovely? No matter what age we are, what draws us to it?” Beatty blew out the flame and lit it again. “It’s perpetual motion; the thing man wanted to invent but never did. Or almost perpetual motion. If you let it go on, it’d burn our lifetimes out.”