Harvard Professor Richard Pipes

Prof. Richard Pipes and Russian History

a discussion about Professor Pipe's

"polemical view of Russian history"

"For Pipes to be optimistic about democracy and capitalism "taking root" in Russia is so naive it astonishes me."

From: milam@pacbell.net

Date: Mon, 12 Jan 1998 01:22:51 -0800

To: cybrgbl@deltanet.com

Subject: Richard Pipe's Comments

X-URL: http://www.intellectualcapital.com/issues/98/0108/icworld.aspAt 01:22 AM 1/12/98 -0800, you wrote:

What has always been astonishing to me while reading Pipe's polemical view of Russian history is his nearly unquestioned assumption that American "democracy" and "capitalism" is vastly "superior" as a way of life to that of the Russian way. From the perspective of a distinguished Harvard professor, "our" way of life certainly must seem superior to the average Russian's economic struggle from day to day. Americans, especially affluent Americans, tend to equate the value of life with material success. In fact, Pipe's work demonstrates a certain cultural blindness to the possibility that "progress" could be measured in any other way than material and economic. I doubt that Pipes ever spent a few weeks in a Russian village living and interacting with the Russian masses. Russians, in general, do not equate a satisfying life to economic and material success as closely as Americans tend to do. In fact, most Russians tend to equate the "self interest" inherent in capitalism as inimical to their way of life. And it is. There was no Thaomas Jefferson in Russia, and the enlightenment was forced on them by Peter the Great and Catherine. It was not a "natural" development of the Protestant conquest of North America as it was here. That Protestant drive for self justification that created America in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries was a historical drive that cannot be repeated arbitrarily in Russia in the 21st. And it will not be. To stand Marx on his head and following Weber, I would say in the case of Russia that the cultural spirit of the people will have as much to do with the future economic structure of Russia as the economics imposed by international conditions. And Russia is a land of peasants who are traditionally sceptical of systems and scornful of self interest. Russians are not motivated by a democratic voice and the self interest of a "free" market. I do not claim to know what motivates them, but it has something to do with what we in the west often scorn as "intangible" and "spiritual." For Pipes to be optimistic about democracy and capitalism "taking root" in Russia is so naive it astonishes me. The ignorance of the importance of cultural history in the development of governmental institutions and economic systems is remarkable. Maybe Pipes should work sixty hours a week with no medical insurance and no retirement plan like I do. Then maybe he might have a more critical attitude toward our system. Maybe he could dig potatoes in a Russian village with the Russians and enjoy a bottle of vodka afterwards and listen to their attitude toward those who take and do not give back in the name of creating a material-based, "democractic" society. Pipe's firm conviction that Russia should be like America escapes me completely. It is not sound historically, and if I were a Russian, would I want to be reduced to being a person who worked all the time merely so that I can buy things? I find it less and less convincing when "experts" who prosper from a system want to impose that system on others. Let alone a whole country. The Russian reticence toward capitalism comes from a cultural tradition that is sceptical of the individual taking advantage of the group. I am not convinced, as Pipes is, that this is a fundamentally wrong attitude.

Dear Milam,

Life is tough everywhere in the world. However, it is much tougher in Russia - today, yesterday, probably tomorrow - than in most of the rest of the world. All I would like to see in Russia is some society where people did not want for the basics and live like a bunch of cattle despised and maltreated by their government. I am not suggesting they work 60 hours per week, although Stalin did everything he could to make that happen. And I do not suggest that they become like those in the West, who supposedly only live to work and shop (I could show you many many examples of persons in the West who are not so - starting with myself). I just would hope for the first time in its history Russians could enjoy a little political freedom without being terrorized by their government while enjoying the material benefits of the sweat of their brow.

Yet Russian society seems so corrupt and the Russian people so averse to taking responsibility for their future in terms of the 21st century that it makes one almost despair. I think the vast majority of people would just like a Russia at peace with itself and the rest of the world - not starving in abject penury, not exporting revolution to its neighbors, etc. But Russian political life is so immature - although this may be slowly and painfully changing - that they hardly know what they want. You mention that the "Russian reticence toward capitalism comes from a cultural tradition that is skeptical of the individual taking advantage of the group." That reminds me of a story a Russian professor told me once: "In England, if a peasant does well and acquires a new cow, his neighbors think him prosperous and respect him. In Russia, if a peasant does well and buys another cow, his neighbors automatically suspect him of thievery and kill the cow in revenge." Such an attitude does not bode well for the economy of the country as initiative is stifled and the industrious penalized. This has been the history as a country like Russia rich in agricultural resources has had trouble feeding its people. Look at the pathetic spectacle of thousands of Russian soldiers urgently being carted off to help labor during the critical weeks of the harvest season!

You seem to admire the collectivist spirit in Russia. But look at how some approximately 5% of the American population work in agriculture but still grow more than enough food for the 270 million people in the country. And look at the following that I read recently from the chariman of a Russian collective farm: "We work badly, we live poorly, we lose money. But at least we still have the collective." This seems to me the reality of the "collectivist" spirit you claim is so powerful in the Russian character. It is the same loser sentiment one hears from the rural militiamen in Idaho and unquiet urban minority activists in America. "It may be a piece of shit, but it is OUR piece of shit!" they exclaim. One need do better. You talk of harvesting potatoes and then sharing a friendly bottle of vodka with comrades. I suspect the reality for Russian peasants is more in the nature of drunken squalor, large-scale, and pervasive ignorance. They say that bartering has all but replaced money and that anything not nailed down is stolen! The world progresses and the Russian peasantry are stuck in the same old rut. Why become an independent farmer and take responsiblity for your own future?

It is not realistic to preach a back-to-the-earth pre-Soviet era Dosteyevskian/Tolstoyan vision of 19th century Russian peasant spirituality -- which I suspect was as much myth as reality -- in 1998. One hears the old Communists and neo-Slavophiles talk of the infection of freedom and the poison of selfish Western individualism, and it makes me wonder that perhaps no prosperous social order ever will bloom in the inhospitable soil of Mother Russia. The way of life enjoyed in the United States and the rest of the West might not be the exemplar, but if you measure it up against that of Russia suffering today and yesterday you can draw the inevitable conclusions. This has a lot to do with the many thousands of Russian émigrés who live around me here in Los Angeles. They see the way of life they had in the Soviet Union and now in modern Russia, and they see what other parts of the world have to offer. And they vote with their feet and they leave. I would argue that they do not leave and undergo so much trauma and dislocation because they hate Russian culture or their Russian countrymen or the way of life there. I suggest that they do so because the larger political and economic life of that country has been, is, and most likely - at least in the near future - will be a disaster. This has everything to do with government.

Russia, in its colorful history, has produced peerless music, literature, dance. But Russia has never had as its forte government. Russia surely does not have its shit together today in that respect - everyone with eyes to see recognizes that; everywhere people respect what works. But this has to do with a Russia which for many centuries has treated its people as little better than dogs; the crises which erupted after the fall of the Soviet Union, of course, had everything to do with the larger problems which had plagued the country for decades - no!, centuries (re: Tsarist absolutism, the Commissar culture)! Of course the people then take little responsibility for themselves and the polis. Without such a change in responsibility, the endemic corruption and brutality and alcoholism of Russia will not change, in my opinion. Russia need breed a truly civic culture and something more than a country of party officials and prols, aristocrats and serfs, masters and slaves. When I listen to Slozhenitsyn or some other Romantic slavophile talk about the spiritual destiny of a resurgent Russia led by the strong hand of some righteous divinely appointed autocrat which brings obedience and unity to the people without any kind of institutional mediation or independent civil society, I think they will repeat the mistakes of the past time and time again.

The world is every day smaller and smaller while education is more important than ever as the slow get left behind as we enter the 21st century in a wired world. What is true yesterday might not be true today; and Russia needs to do a lot better in finding out exactly what will be its path in the future. Only at such a point can that country be said to be "mature" politically. Although improved in comparison to seven years ago when the corpus of the Soviet Union was unceremoniously dumped into the ashbin of history, Russians are a long way from making such claims of maturity today. Everyone with eyes to see realizes that.

I would say it again: Life is tough everywhere. But it sure is a hell of a lot tougher in some places than in others.

Very Truly Yours,

Richard Geib

Date: Tue, 20 Jan 1998 10:18:59 -0600 (CST)

From: milam@pacbell.net

Subject: Re: Pipe's Comments

To: Richard Geib (cybrgbl@deltanet.com)Richard

I appreciate and agree with many of your ideas about Russia. The thrust of my comments were directed at Richard Pipes who has academized U.S. Cold War cultural blindness in regard to Russia. He was one of Reagan's chief consultants on the Soviet Union, for heaven sakes, and the Reagan administration was not one of the choicest fruits of the Western cultural tradition. He is also a Harvard don and part of the elitist culture in America, a culture that is comfortable and secure and tends to believe that all cultures would be better off to adapt the American style of life in which success and satisfaction in life is equated with the selling and acquiring of goods. In such a culture, all values tend to be reduced to exchange value, and many traditional values--not always backward--are forgotten or lost.

The parable that you related about the peasant and the cow in England and in Russia has a corollary. The English peasant manages to gain an economic advantage over his fellow peasants so that they are making profit for him. The Russian peasants manage to alleviate the worst aspects of the loss of the cow for the unfortunate peasant. Russia is primarily a land of peasants; the Revolution and the purges drove out or eliminated most of the aristocracy and the legacy of the nobility of traditional agriculutral society. Russian peasant society is basically communal; thus, it is not hard to understand the appeal of socialism. This fact has good and bad consequences. Russians in general do not like to see someone get ahead and personally profit at the expense of the group. On the other hand, they are willing to give up personal gain for the good of the group. This is, I believe, the major cultural distinction between the West, with its glorification of individual achievement, and Russia. It is, as well, something that must be kept in mind when thinking about Russia's future. Most experts that I hear on the question reduce the discussion to theoretical questions of economics and government structures. Those are important; nevertheless, those things will develop within the context of Russia's folk, peasant culture. I may sound like Spengler here, but from what I read, this aspect is all too often ignored.

Your idea about the development of civic institutions in Russia is the thesis of a book by Jonathan Steele entitled "Eternal Russia," an excellent book that is objective and balanced compared to Pipes's work which I find to be highly polemical. Steele was Moscow correspondent for "The Guardian" and lived in Russia for several years. I highly recommend it. It is the finest book about the events of the early 90s that I have read. David Remnick's books are also very good, but he writes journalism. Steele writes history and analysis.

Nevertheless, the development of civic institutions as a counterweight to monolithic government is probably the only way Russia will avoid another totalitarian system. The prospects are not good. Two years ago, I spent a year in Russia teaching at Irkutsk State University in Siberia. I spent much time in small Russian villages and much time discussing the future of Russia with people from all political positions. One thing that almost all Russians share is a belief that a strong leader will lead them out of their troubles and make Russia great again. I am not convinced that this attitude and the basic peasant mentality will easily or quickly change. Intercourse with the rest of the world can have a major influence, but the development of civic institutions is something that probably has to come about in some long and "natural" development. I am not sure how that can occur.

Are you familiar with the ideas of Nickolai Danilevsky? Or Dostoevsky's "Diary of a Writer"? The ideas of these two radical nationalists can give one an idea of the daunting task of creating a Russia in which individual rights are respected in the context of the "national destiny."

I suppose the pessimistic view that can come out of this is the idea that Russians often willingly sacrifice their own comfort and at times person for the cause of the Third Rome and Orthodoxy. As bizarre as this may sound to Americans of the 21st century, I found it to be harrowingly true to a high degree. Often when Russians today talk of their family members lost during the Stalin years, they do so with a sense of inevitability and necessity.

Thanks for the thoughts,

M

Dear Milam,

I read your comments with no little interest and amazement, as I always place enormous stock in such first-hand experience. That Russians after Lenin and Stalin - not to mention Tsars innumerable! - could still find government by a single powerful leader attractive seems to symbolize the triumph of optimism over experience. One begins to lose respect for the average Russian peasant and his "folk culture" when one hears such things. It seems they can hardly see farther than their own nose, and would follow any demagogue or blowhard if he was "strong" or promised the moon. These Russian peasants you write about sound like a bunch of good-natured sheep! One wonders if they await another wolfish despot ready to devour them by the tens of millions!

Well, this will all be worked out in Russia by the Russians themselves. I just hope if they decide to flush themselves down the toilet they do so without pulling anyone down with them. Perhaps it is a self-fulfilling prophecy in thievery-ridden Russia that one person succeeds only at the cost of the larger community. Perhaps, as in the parable you tell me, Russia in the best case scenario will be not much more than "unfortunate peasants" whose misery is alleviated by killing someone else's cow.

Very Truly Yours,

Richard

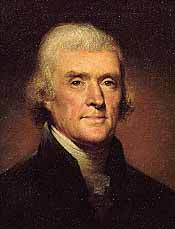

Can Russia realize a functioning constitutional democracy without an Enlightenment tradition? Or is despotism in Russia an inherently national trait? Respondent: "There was no Thomas Jefferson in Russia, and the enlightenment was forced on them by Peter the Great and Catherine."

Thomas Jefferson

(1743-1826)"I have no fear but that the result of our experiment will be that men may be trusted to govern themselves without a master." -- Jefferson in 1787 letter to David Hartley

Date: Wed, 13 Oct 1999 19:00:30 -0700 (PDT)

From: webmaster@rjgeib.com

To: questions-feedback@rjgeib.com

Subject: Form Submission from www.rjgeib.comX-UIDL: 6a6b8115daf91ce38552f741eee9519e EMAIL_ADDR: feedback-questions@rjgeib.com

EMAIL_SUBJECT: Feedback and or Questions

RETURN_URL: http://www.rjgeib.com/about-me/guest/thank-you.html

Name: Greg

email: lmorskoi@earthlink.netcomments:

I want to begin by complimenting you on a truly fine site. I found it through the Jane Fonda and Vietnam War page; a friend had forwarded excerpts from several accounts of captive servicemen and their experiences with Ms. Fonda during her visit to N. Vietnam. Knowing little of the context for these accounts, I checked out your page. What is the consensus on the authenticity of the transcript. The language appears rather scripted to me; perhaps it was. The most interesting feature of the page for me, however, was the collection of responses. Kudos to you for not being baited and responding to the ad hominem attacks in kind.My main motivation for writing is you Russia and democracy page. While I share your frustration over the glacial pace of both economic reform and the evolution of democratic institutions, I think your assessment of the inexplicable apathy of the Russian people is an excellent illustration of how different our cultures are and why Americans view Russia with growing exasperation. My reaction to the anecdote about the jealous peasants and the cow was, when I first heard it, much the same as yours. The peasants' reaction to their neighbor's prosperity seems counter-productive. In our age of mechanization and surplus production, this type of rabid communalism seems absurd. It is important to remember, however, that our country evolved at a time shaped by the political ideology of Rousseau and the budding Industrial Revolution. Our culture (if one can speak of an American culture) was shaped by these influences. Russian communal culture, which, I believe, profoundly effects thhe economic, social and political behavior and attitudes of contemporary Russians, evolved in a region where even subsistance was threatened by a considerably less forgiving natural environment and the constant incursions of agressive, militarily superior neighbors. The rugged individualism of the early American farmer striking out into the wilderness to stake his claim does not hold the same heroic value in Russian history. Vanya Iablosemechko (my invariably incorrect translation for Johnny Appleseed)would not have made it. The economies of scale and security in numbers made communal settlements viable where individual homesteads failed. Laws and customs, some rather draconian, were established to reinforce the community and to suppress the individual. Individualism was not only dangerous to the maverick; it threatened the survival of the larger community which depended on his/her participation. Keeping this is in mind, the hostility and suspicion with which the peasant community looks at the entrepreneurial individual is perhaps not so surprising. Social modes created to sustain life have deep roots and persist long after the conditions that gave rise to them have changed. Furthermore, while conditions in modern Russia do not bear a particularly close resemblance to those of the 6th-century forest-steppe region, some variation of communal living, both voluntary and compulsory, has been a feature of life for most of Russia's population until the present day.

The appeal to a strong prince or tsar to come to the rescue of the people by smiting their foes and freeing them from the abuses of evil lords and ministers is also very deeply rooted in Russian literary and political traditions and the collective psyche.

How is life treating you?: Ebb and flow, wax and wane

Findout: Just surfed on in!

Age: 30

State?: CA

Country?: USA

Back

to Russian

and Democracy Page

Back

to Russian

and Democracy Page