"Why I am Not a Communist"

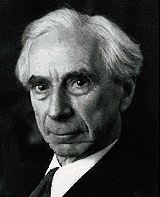

by Betrand Russell

"I am completely at a loss to understand how it came about that some people who are both humane and intelligent could find something to admire in the vast slave camp produced by Stalin."

I n relation to any political doctrine there are two questions to be asked: (1) Are its theoretical tenets true? (2) Is its practical policy likely to increase human happiness? For my part, I think the theoretical tenets of Communism are false, and I think its practical maxims are such as to produce an immeasurable increase of human misery.

The theoretical doctrines of Communism are for the most part derived from Marx. My objections to Marx are of two sorts: one, that he was muddle-headed; and the other, that his thinking was almost entirely inspired by hatred. The doctrine of surplus value, which is supposed to demonstrate the exploitation of wage-earners under capitalism, is arrived at: (a) by surreptitiously accepting Malthus's doctrine of population, which Marx and all his disciples explicitly repudiate; (b) by applying Ricardo's theory of value to wages, but not to the prices of manufactured articles. He is entirely satisfied with the result, not because it is in accordance with the facts or because it is logically coherent, but because it is calculated to rouse fury in wage-earners. Marx's doctrine that all historical events have been motivated by class conflicts is a rash and untrue extension to world history of certain features prominent in England and France a hundred years ago. His belief that there is a cosmic force called Dialectical Materialism which governs human history independently of human volitions, is mere mythology. His theoretical errors, however, would not have mattered so much but for the fact that, like Tertullian and Carlyle, his chief desire was to see his enemies punished, and he cared little what happened to his friends in the process.

Marx's doctrine was bad enough, but the developments which it underwent under Lenin and Stalin made it much worse. Marx had taught that there would be a revolutionary transitional period following the victory of the proletariat in a civil war and that during this period the proletariat, in accordance with the usual practice after a civil war, would deprive its vanquished enemies of political power. This period was to be that of the dictatorship of the proletariat. It should not be forgotten that in Marx's prophetic vision the victory of the proletariat was to come after it had grown to be the vast majority of the population. The dictatorship of the proletariat therefore as conceived by Marx was not essentially anti-democratic. In the Russia of 1917, however, the proletariat was a small percentage of the population, the great majority being peasants. it was decreed that the Bolshevik party was the class-conscious part of the proletariat, and that a small committee of its leaders was the class-conscious part of the Bolshevik party. The dictatorship of the proletariat thus came to be the dictatorship of a small committee, and ultimately of one man - Stalin. As the sole class-conscious proletarian, Stalin condemned millions of peasants to death by starvation and millions of others to forced labour in concentration camps. He even went so far as to decree that the laws of heredity are henceforth to be different from what they used to be, and that the germ-plasm is to obey Soviet decrees but that that reactionary priest Mendel. I am completely at a loss to understand how it came about that some people who are both humane and intelligent could find something to admire in the vast slave camp produced by Stalin.

I have always disagreed with Marx. My first hostile criticism of him was published in 1896. But my objections to modern Communism go deeper than my objections to Marx. It is the abandonment of democracy that I find particularly disastrous. A minority resting its powers upon the activities of secret police is bound to be cruel, oppressive and obscuarantist. The dangers of the irresponsible power cane to be generally recognized during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but those who have forgotten all that was painfully learnt during the days of absolute monarchy, and have gone back to what was worst in the middle ages under the curious delusion that they were in the vanguard of progress.

There are signs that in course of time the Russian régime will become more liberal. But, although this is possible, it is very far from certain. In the meantime, all those who value not only art and science but a sufficiency of bread and freedom from the fear that a careless word by their children to a schoolteacher may condemn them to forced labour in a Siberian wilderness, must do what lies in their power to preserve in their own countries a less servile and more prosperous manner of life.

There are those who, oppressed by the evils of Communism, are led to the conclusion that the only effective way to combat these evils is by means of a world war. I think this a mistake. At one time such a policy might have been possible, but now war has become so terrible and Communism has become so powerful that no one can tell what would be left after a world war, and whatever might be left would probably be at least as bad as present -day Communism. This forecast does not depend upon the inevitable effects of mass destruction by means of hydrogen and cobalt bombs and perhaps of ingeniously propagated plagues. The way to combat Communism is not war. What is needed in addition to such armaments as will deter Communists from attacking the West, is a diminution of the grounds for discontent in the less prosperous parts of the non-communist world. In most of the countries of Asia, there is abject poverty which the West ought to alleviate as far as it lies in its power to do so. There is also a great bitterness which was caused by the centuries of European insolent domination in Asia. This ought to be dealt with by a combination of patient tact with dramatic announcements renouncing such relics of white domination as survive in Asia. Communism is a doctrine bred of poverty, hatred and strife. Its spread can only be arrested by diminishing the area of poverty and hatred.

from Portraits from Memory published in 1956

Back

to Commuism:

Opiate of the Intellectuals Page

Back

to Commuism:

Opiate of the Intellectuals Page