Frederick Nietzsche

prophet of the modern

1844-1900

THE HAMMER SPEAKS

"Why so

hard?" the kitchen coal once said to the diamond. "After all,

are we not close kin?'

Why so soft? O, my brothers, thus I ask you: are you

not after all my brothers?

Why so soft, so pliant and yielding? Why is there so

much denial, self-denial, in your hearts? So little destiny in your eyes?

And if you do not want to be destinies and inexorable

ones, how can you one day triumph with me.

And if your hardness does not wish to flash and cut

and cut through, how can you one day create with me?

For all creators are hard. And it must seem blessedness

to you to impress your hand on millennia as on bronze-harder than bronze, nobler

than bronze. Only the noblest is altogether hard.

This new table, O my bothers, I place over you: become

hard!

Frederick Nietzsche

Zarathustra, III .29

FREDERICK NIETZSCHE:

THE WILL TO POWER - BECOME HARD

"I am absolutely convinced that the gas chambers

of Auschwitz, Treblinka, and Maidanek were ultimately prepared

not in some ministry or other in Berlin, but rather at the desks

and in the lecture halls of nihilistic scientists and philosophers."

Viktor

Frankl

The Doctor and the Soul

"[In place of religious belief] Nietzsche

rightly perceived that the most likely candidate would be what

he called the "Will To Power," which offered a far more comprehensive

and in the end more plausible explanation of human behavior than

either Marx or Freud. In place of religious belief, there would

be secular ideology. Those who had once filled the ranks of the

totalitarian clergy would become totalitarian politicians. And,

above all, the Will to Power would produce a new kind of messiah,

uninhibited by any religious sanctions whatever, and with an

unappeasable appetite for controlling mankind. The end of the

old order, with an unguided world adrift in a relativistic universe,

was a summons to such gangster-statesmen to emerge. They were

not slow to make their appearance."

Paul Johnson

Modern Times

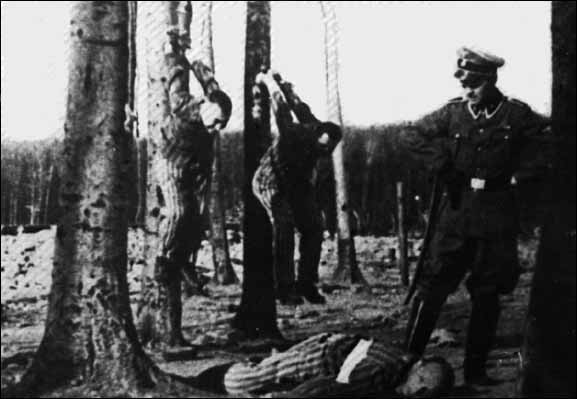

The SS cultivated and honored the ability to kill human beings en

masse without any remorse for the greater glory of the Nazi

cause.

Let us

acknowledge unprejudiced how every higher civilization hitherto

had originated! Men with a still natural nature, barbarians in

every terrible sense of the word, men of prey, still in possession

of unbroken strength of will and desire for power, threw themselves

upon weaker, more moral, more peaceful races (perhaps trading or

cattle-rearing communities), or upon old mellow civilizations in

which the vital forces was flickering out in a brilliant fireworks

of wit and depravity. At the commencement, the noble casts was

always the barbarian caste: their superiority did not consist first

of all in their physical, but in their psychical power - they were

complete men (which at every point also implies the same as "more

complete beasts").

It is impossible not to recognize

at the core of all these aristocratic races the beast of

prey; the magnificent blond brute, avidly rampant for spoil

and victory; this hidden core needed an outlet from time

to time, the beast must get loose again, must return into

the wilderness - the Roman, Arabic, German, and Japanese

nobility, the Homeric heroes, the Scandinavian Vikings, are

all alike in this need... They enjoy their freedom from all

social control, they feel that in the wilderness they can

give vent with impunity to that tension which is produced

by enclosure and imprisonment in the peace of society, they

revert to the innocence of the beast-of-prey conscience,

like jubilant monsters, who perhaps come from a ghostly bout

of murder, arson, rape, and torture, with bravado and a moral

equanimity, as though merely some wild student's prank had

been played, perfectly convinced that the poets have now

an ample theme to sing and celebrate.

Frederick Nietzsche

The Genealogy of Mortals

MEMBERS OF A "WEAKER RACE?"

Holocaust victims of Adolf

Hitler's Third Reich lay piled on top of one another.

(This correspondence between Rich

Geib and John

Barich deals with whether or G.W.F. Hegel and Frederick

Nietzsche had anything to do with the rise of totalitarian

governments in the 20th century.)

"Take but degree away, untune that

string,

And hark, what discord follows! each thing meets

In mere oppugnancy:...

Then every thing includes itself in power,

Power into will, will into appetite."

William Shakespeare

Los Angeles, California

April 15, 1995

Dear John,

One could say that the most deadly

threat a prophet or philosopher runs is the risk of being misunderstood

or misinterpreted. And understood in a vacuum, religion is one

of the most noble and uplifting of the human discourses, undoubtedly

a support and consolation to untold numbers. However, perhaps

no other single source has caused more bloodshed and misery in

human history. Untold numbers of atrocities have been committed

in the name of religion, with the perpetrators firmly convinced

that what they were doing was sanctioned in the eyes of God.

Perhaps it is a paradox of mankind that so many of the beautiful

ideas and moral laws invented by the mind of man have been so

corrupted and misshapen in their application in the world of

men. Notwithstanding the daily importance of religion to so many,

I tend to share the view of Lucretius: "Religion is a disease

born of fear and a source of untold misery." And although

ideas may be born in the antiseptic world of thought and contemplation,

they have consequences out in an imperfect world replete with

messiness, strife, and evil.

I grant you the argument that to

personally blame Frederick Nietzsche or G.W.F. Hegel for the

sins of 20th century Germany is a mistake, as well as a gross

oversimplification. Both were men of letters who surely would

have shirked from naked violence and cruelty. Understood in the

correct historical context, their philosophies both seek to bring

about what they individually saw as a greater good. The Nietzschian "superman" and

the Hegelian concept of the unity of the Absolute Idea are both

arguments for a mankind that is improved and enlightened. The

problem is that these highly sophisticated philosophers and their

ideas are to be read and interpreted by men who will see in them

what is important to them. In their enactment in the world of

man, "pure" ideas are often distorted and used for self-serving

purposes. This is a key problem of intellectuals: they lack a

common sense in the world outside of the mind, and ideas are

all too vulnerable in the context of money, war, and power. In

taking thought out of the ordered world of the intellect and

trying to enact it in the flawed world of mankind, too often

the spirit of the thing is killed with disastrous results. As Pinkerton (in

my opinion) accurately states in his article, "Ideas may start

in ivory towers, but they have consequences for real people."

To read Nietzsche is to come under

his spell. His peculiar power may come from his fusing the power

of the prophet with the epic lyricism of the poet. His writing

is pregnant with image and an emotive power that is dangerous

for a philosopher and there is a glorification of the heroic

and spontaneous which calls to something deep in the primal heart

of man the animal. Can we be surprised that so much of what he

wrote appealed to the worst in mankind?

Nietzsche called for the Superman. Mussolini

and Hitler answered

the call. It does not matter that in all probability Nietzsche

would have scorned them as perverters of his doctrine, would

have opposed them bitterly. It does not even matter that

had Nietzsche never written these men would in all probability

have come to power much as they did. They have found a use

for Nietzsche, a use he probably never intended his words

to provide.

Crane Brinton, Nietzsche

As you noted, Nietzsche was an unparalleled master

at dissecting what was wrong with European Christianity: how people

simply mouthed the slogans without believing in them ("God is

dead"). And it is true that his ideas landed like bombs among

the comfortable bourgeoisie of the liberal democracies.

But in attacking so powerfully

what was wrong with the "slave morality" of Christianity,

Nietzsche opens the way for disaster by glorifying so powerfully

a radical individualism and self-assertiveness. A university

professor might argue this point by arguing the historical

context and author's intent, but I argue that in the real

world of mankind - full of brooding souls with animal passions

residing just below the veneer of civility - there exists

dangerous forces that when not controlled can lead to disaster.

Nietzsche must be understood as against Christianity; to

see him as ultimately in favor of anything else definitive

is to mistake his intent and enter perilous territory. He

simply argues the Will to Power, for the unleashing of the Dionysian spirit

to run joyfully upon the earth. In real life, this all too

often means slaughter and domination. It is precisely the

Christian precepts of love of neighbor and humility which

serve as a check to the darker side of man. What does this

instinct to Power inflame in the breast of man? The best

or the worst? To what end should power ultimately serve?

Nietzsche does not directly address these questions, although

one may assume and draw inferences. I argue that in real

life such fever-pitched emotional pleas for assertiveness

and unbridled individualism speak directly to what can be

worst in man, unleashing his animal side unchecked. You mentioned

that a Christian country (the United States) defeated a Nazi

Germany embodying such rabidly aggressive values. But you

forget the Germans were fighting almost the whole world.

And they almost won.

Frederick Nietzsche was a man

of books and universities who grew up surrounded by doting

female love in a strictly pious Christian household. Professionally,

he was first a university professor and then a recluse writer/philosopher

who never had a family, nor love affair worthy of the name.

In short, he never was much of an active participator in

the world of men. So much of what he writes glorifies the Dionysian aspect

of mankind, the man of destiny impressing his will upon the

wax of history. This is one thing in the sanitary world of

pure thought, and quite another in the world of politics,

war, and power. Nietzsche never served as a soldier, never

killed anyone, nor watched anyone die a violent death. If

he had, he may have been more cautious in extolling the virtues

of the strong and the powerful (understanding better the

price and the pain). And the feverish and intemperate tone

of Nietzsche's prose is as important as what he says - can

people hardly be blamed for misinterpreting him?

The "superman", in real life,

finds its more likely incarnation in Napoleon in the 19th

century and more dynamic dictators in the 20th - an age,

in part due to the prophet Nietzsche, where traditional ideas

of history and justice were turned on their head and everything

was permitted. The

Good, the True, and the Beautiful were cast aside with

contempt as questions of power and politics became pervasive

and all-important. The modern era began with the person of

Napoleon, claims French historian Jean-Richard Bloch, and

it is an age defined by its unlimitedness, its concept of

power without religious or moral counterweight. It has seen

a vigorous rejection of reason and liberalism and a consequent

return to the older and darker worldview of Hobbes where

mankind suffers "a perpetual and restless desire of power

after power, that ceaseth only in death." I look at the

old black and white newsreels from the inter-war period of

the 1930s punctuated with speechifying jackbooted thugs gesticulating

wildly appearing to bark gunpowder, and other machine-like

leather jacketed revolutionaries grimly promising death to "class

enemies" everywhere around the world, and my hearts sinks

through my shoes. Humanity seemed on the verge of plunging

into a new Dark Age of ubiquitous violence and cruelty! Was

this progress?

When I read Nietzsche, I am reminded

of watching a training film in the Sheriff's Academy where

a prison gangmember tells of stabbing another inmate to death.

Standing triumphantly over the dying man and watching his

life blood flow out, the gangmember seems to transcend his

own mortality: "Man, I felt like a God!" Flush with

the power to take a life, to play God on earth, unrestrained

by moral constraints, indomitable and immortal; when Nietzsche

preaches so eloquently in favor of the Will to Power in his

writings, he preaches precisely to this aspect of humanity

in real life. Once more: to read Nietzche is all too often

to fall under his strange spell; his prose possesses a beauty

and power unrelated to the logic of his philosophy, it being

so strident with the spirit of poetry. As a philosopher Nietzche

writes perhaps too well for his own good - one is captivated

by his passion and emotion almost more than by his reasoning.

Nietzsche is spiritually akin to Homer, praising the mighty

Odysseus with Priam and his family murdered at his feet.

Yet no matter what the reason or need, for those possessing

a moral sense and an active conscience the killing of another

human being is always a grave and tragic thing.

To question religion and the

existence of God is one thing. To take it a step farther

and call into question any morality we may have inherited

from our Judeo-Christian heritage is another more dangerous

step which has led to barbarism and spectacular crimes in

the 20th century, in my opinion. While rejecting and attempting

to destroy the "degenerate" bourgeois order of the late 19th

century, Nietzsche never put much up in way of an alternative.

Like the baby-boomers of America in the 1960s, Nietzsche

broke down traditions without establishing anything in their

place. Nihilism was the result, and new unscrupulous forces

rushed in to fill the vacuum. As Walter Lippman observed, "When

men can no longer be theists, they must, if they are civilized,

become humanists." With his call for mankind to transcend

its "weakness," can Nietzsche call himself a humanist?

I agree with T.S. Eliot when

he talks of a certain "wisdom of our ancestors"; and we reject en

masse this wisdom at our own peril, in my opinion. Realistic

and effective control of evil and disorder, Milton wrote

in Aeropagitica, depends heavily on "those unwritten,

or at least unconstraining laws of virtuous education, religious

and civil nurture." This sense of tradition and custom, as

Plato recognized, are "the bonds and ligaments of the commonwealth,

the pillars and sustainers of every written statue." When

a society cuts itself off from the past by seeking its transcendence,

it stands poised to plunge into the abyss. As the French

and Russian Revolutions, Nazi dictatorship, and many other

instances of political violence in the last two hundred years

have shown, the dream of burning everything down to build

up a "new society" or "new mankind" on its ashes has proven

a nightmare.

As for my part, I will love man

as I find him: both hard and soft, good and evil, infinitely

complex and ambivalent - and not something to be "overcome." And

unlike Nietzsche, I have seen people die violent deaths in

pain, screaming and crying. I have seen many die this way

- as well as meet the people who murdered them in what might

be the most humbling and sobering experiences of my entire

life. For this reason, I cannot help when I read Nietzsche

to feel a certain disgust and contempt. We are all flawed

and frail creatures, including Nietzsche. Christian compassion

and charity starts from exactly this point of reckoning.

Also a university professor,

G.W.F. Hegel suffers from some of the same defects as Nietzsche.

Hegel was not the first nor the last intellectual to see

in the victories of Napoleon over the old aristocratic order

of Europe the dawning of a new age defined by the principles

of liberty, fraternity, and egalitarianism enunciated during

the French

Revolution. And in the context of late-18th century Germany

full of tiny backward and decadent fiefdoms, the phenomenon

of a powerful unified State under the direction of an enlightened

ruler seemed a desirable idea. Hegel held that the Enlightenment

principles of reason, liberty, and freedom could be propagated

upon a superstitious and ignorant world by a powerful centralized

government animated by beneficent motivations. It is easy

to see the superficial attractiveness of this specious reasoning.

Yet it is well to examine what

happened to so many of the Romantics after the fall of Napoleon:

the sense of betrayal by embittered writers and artists disillusioned

by Napoleon's crowning himself Emperor, his violating the

principles of the French revolution, and Europe left yet

again bloodied and in rubble in the name of tyranny and a

greed for power. No matter the casuistry or noble intentions

of his thought, Hegel is fundamentally flawed in constructing

a theory of history placing the State in so central a place

in the unraveling of world history. Hegel argues for a time

in the future when conflicting Ideas (the "dialectic")

will end in a fusion of the "Absolute Idea" - a sort

of unity of all rational ideas equaling the totality of all

human experience and knowledge. Truly only a paradise that

a philosopher could love, Hegel writes of a type of utopia

brought about under the aegis of the Nation-State where mankind

is to be united as a whole in the Absolute Idea. The heaven

of Hegel is to be a state of mind where reason and pure thought

reign supreme, and the mind of man is finally unified in

the One. Hegel rejects individualism and political democracy

as producing alienation and a lack of community in man; the

important is the culture of a race ("volksgeist")

embodied in the State during a particular stage in the unfolding

of human history moving towards the One. "All the worth

which the human being possesses in all spiritual reality,

he possesses only through the State...," Hegel writes, "The

basis of the State is the power of reason actualizing itself

as Will." Wrong. In a totalitarian country, the basis

of the State is naked power - the propagation and corroboration

of power, and the accumulation of more power. In defining

the State as the principal actor in the flow of history and

the key to a future union with the Absolute Idea, Hegel makes

the argument in real life for totalitarian government.

More damaging still is the powerful

influence Hegel had on Karl

Marx and his subsequent development of communism, having

such profoundly damaging effects on world history. How many

people have been slaughtered by communist state organs under

the ideological

justification that the Party need perform its historical

role in bringing about the end of the human "dialectic" ushering

in the ensuing paradise that is consequently promised? How

many millions

of Communist Party faithful were weaned on the sustenance

of "scientific socialism" and "objectively historical

laws," deriving the germ of its idea from the philosophy

of Hegel? I am not arguing that Hegel is directly responsible

for the crimes of communism throughout history. I am simply

arguing that through naiveté and a lack of common sense Hegel

indirectly helped to construe a political system whose natural

application in the real world was a poison the world has

only just begun to expunge from its system. Hegel was in

effect one of the first modern constructors of the totalitarian

ideology. The mixing of an impersonal ideology with the awesome

power of an aggressive modern State was an idea unfortunately

whose time had truly arrived in the 19th and 20th centuries.

With perfect 20/20 hindsight, today we see clearly that in

giving such unlimited power to the State we are paving the

way to unmitigated disaster.

It is through the practical genius

of such political thinkers as John

Locke and the Baron

de Montesquieu that was conceived a State with divided

powers and checks and balances. It is an ideology of limited

government that is structurally designed to resist tyranny

with certain "inalienable rights" encoded in law. Encapsulated

in the United

States Constitution, this has provided a success in real

life that none of the totalitarian

governments has enjoyed. Enlightenment Anglo-Saxon and

French political thought moved to praise and protect the

individual and the minority rights of citizens. It is the freedom

from government oppression and tyranny.

On the other hand, the Germanic

romantic thinkers such as Hegel, Fichte, Schiller all stressed

the importance of the individual's duty to the collective.

Individual success is defined in the success of the collective,

and concepts such as obedience, loyalty, and devotion are

idolized. The highest calling an individual has is to the

State, in serving the needs of the State; it is the freedom

to obey the State. They do not concern themselves with

individuals as such, but rather look at nations as individual

actors with their respective roles in the historical process.

Nations and cultures are the important organisms of this

world view, possessing their own unique personalities and

psychologies. Not surprisingly, the premier people - or "volk" -

was the Germanic one, supposedly possessing a special role

in the unfolding of world history. A role, of course, they

did play - albeit a bloody and ignominious one. How far is

it from such early Prussian nationalist rhetoric to Adolf

Hitler and his creed: "Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Führer?" (One

people, one empire, one leader.) Is Hitler an

aberration, or is he a uniquely German creation?

You wrote to me, "A democratic

state may have evolved in Germany if not for its late unification

and tragic leap into World War I..." Where are the

intellectual roots for a liberal democracy in German intellectual

thought? Was democracy ever very strong in Germany before

the end of World War II? Extreme nationalism in the 19th

century was not a purely German phenomenon, and was powerful

throughout Europe. But the all too common outgrowth of

nationalism, totalitarianism, found powerful ideological

justifications in such early 19th century German romantic

thinkers like Hegel. I have no doubt that Hegel would have

been shocked and dismayed to see the legacy of his philosophy.

Yet it is precisely Hegel's flawed judgment in calling

for the establishment of an all-powerful State that helped

to create a basis for subsequent political ideologies such

as communism and fascism. And it is directly the proliferation

of such ultra-authoritarian States that has precipitated

so much of the rape of the individual by the collective

that so besmirches our age. As George Orwell so poignantly

put it in his quintessentially 20th century novel, "1984": "If

you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping

on a human face --- forever."

"Conversation enriches the

understanding, but solitude is the school of genius," wrote historian

Edward Gibbon of another philosopher (Mohammed), just

a short period before the rise of Napoleon and the dawn

of the Modern Age. It is from the realm of pure thought

that man has sought to understand the movement of the stars

overhead, unleash the power

of the atom, and conceive of a moral

law which separates us from the animals. Yet the ordered

and logical world of pure thought is much different from

the world one finds in the society of man. All too often

in formulating their theses, intellectuals (like Nietzsche

and Hegel) have come to show themselves as intensely brilliant

in the former and spectacularly ignorant in the latter.

Sincerely,

Richard

"Society cannot exist unless a controlling

power upon will and appetite be placed somewhere, and the

less of it there is within, the more there must be without...

men of intemperate minds cannot be free. Their passions forge

their fetters."

Edmund

Burke

from Betrand Russell's "A History of Western Philosophy"

"But egoistic passions, when once

let loose, are not easily brought again into subjection to the

needs of society. Christianity had succeeded, to some extent,

in taming the Ego, but economic, political, and intellectual

causes stimulated revolt against the Churches, and the romantic

movement brought the revolt into the sphere of morals. By encouraging

a new lawless Ego it made social cooperation impossible, and

left its disciples faced with the alternative of anarchy or despotism.

Egoism, at first, made men expect from others a parental tenderness;

but when they discovered, with indignation, that others had their

own Ego, the disappointed desire for tenderness turned to hatred

and violence. Man is not a solitary animal, and so long as social

life survives, self-realization cannot be the supreme principle

of ethics."

Buddha

versus Nietzsche

as envisioned by Betrand Russell

|

|