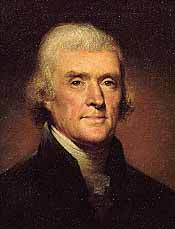

Thomas Jefferson

Virigina Statute for Religious Freedom of 1786

"

II. Be it enacted by the General Assembly that no man shall be compelled

to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever,

nor shall otherwise suffer on account of his religious opinions or belief;

but that all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain,

their opinion in matters of religion, and that the same shall in no wise

diminish, enlarge, or affect their civil capacities."

" II. Be it enacted by the General Assembly that no man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever, nor shall otherwise suffer on account of his religious opinions or belief; but that all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinion in matters of religion, and that the same shall in no wise diminish, enlarge, or affect their civil capacities."

Until the beginning of the Revolutionary War, nine of the thirteen colonies still officially supported one particular religion, called an established church. But the practice had been weakened by the "Great Awakening," and by 1787 only Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Connecticut maintained established religions. In the other states, the support of religious institutions depended on the voluntary contributions of their members.Thomas Jefferson led the fight for religious freedom and separation of church and state in his native Virginia. This brought him into conflict with the Anglican Church, the established church in Virginia. After a long and bitter debate, Jefferson's statute for religious freedom passed the state legislature. In Jefferson's words, there was now "freedom for the Jew and the Gentile, the Christian and the Mohammedan, the Hindu and infidel of every denomination." When the First Amendment to the Constitution went into effect in 1791, Jefferson's principle of separation of church and state became part of the supreme law of the land.

Virigina Statute for Religious Freedom (1786) I. Well aware that Almighty God has created the mind free; that all attempts to influence it by temporal [civil] punishments or burdens or by civil incapacitations [lack of fitness for office], tend only to ... [produce] habits of hypocrisy and meanness and are a departure from the plan of the Holy Author of our religion, who, being Lord both of body and mind, yet chose not to propagate [spread] it by coercions [force] on either, as was in his Almighty power to do; that the impious presumption of legislators and rulers, civil as well as ecclesiastical [religious], who, being themselves but fallible and uninspired men, have assumed dominion [rule] over the faith of others, setting up their own opinions and modes of thinking as the only true and infallible [ones], and, such, endeavoring to impose them on others, have established and maintained false religions over the greatest part of the world and through all time; that to compel a man to furnish contributions of money for the propagation of opinions which he disbelieves is sinful and tyrannical; that even ... forcing him to support this or that teacher of his own religious persuasion is depriving him of the comfortable liberty of giving his contributions to the particular pastor whose morals he would make his pattern and whose powers he feels most persuasive to righteousness ... ; that our civil rights have no dependence on our religious opinions any more than [on] our opinions in physics or geometry; that therefore the proscribing [of] any citizen as unworthy [of] the public confidence by laying upon him an incapacity of being called to offices of trust and emolument unless he profess or renounce this or that religious opinion is depriving him injuriously of those privileges and advantages to which in common with his fellow citizens he has a natural right; . . . that to suffer the civil magistrate to intrude his powers into the field of opinion and to restrain the profession or propagation of principles on supposition of their ill tendency is a dangerous fallacy which at once destroys all religious liberty, because he [the magistrate], being, of course, judge of that tendency, will make his opinions the rule of judgment and approve or condemn the sentiments of others only as they shall square with, or differ from, his own; that it is time enough for the rightful purposes of civil government for its officers to interfere when principles break out into overt [open, or public] acts against peace and good order; and, finally, that truth is great and will prevail if left to herself, that she is the proper and sufficient antagonist to error and has nothing to fear from the conflict, unless by human interposition disarmed of her natural weapons, free argument and debate, [for] errors [cease] to be dangerous when it is permitted freely to contradict them.

II. Be it enacted by the General Assembly that no man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever, nor shall otherwise suffer on account of his religious opinions or belief; but that all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinion in matters of religion, and that the same shall in no wise diminish, enlarge, or affect their civil capacities.

III. And though we well know that this assembly, elected by the people for the ordinary purposes of legislation only, [has] no power to restrain the acts of succeeding assemblies, constituted with powers equal to her own, and that therefore to declare this act to be irrevocable would be of no effect in law; yet, as we are free to declare, and do declare, that the rights hereby asserted are of the natural rights of mankind, and that if any act shall hereafter be passed to repeal the present or to narrow its operation, such act will be an infringement [violation] of natural rights.

![]()