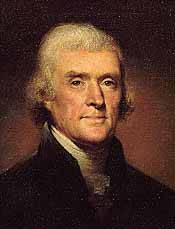

Thomas Jefferson

(1743-1826)

Thomas Jefferson's Last Letter

"May it [the Declaration of Independence] be to the world, what I believe it will be, (to some parts sooner, to others later, but finally to all,) the signal of arousing men to burst the chains under which monkish ignorance and superstition had persuaded them to bind themselves, and to assume the blessings and security of self-government."

Thomas Jefferson, so uniquely American in both his awesome talents and serious shortcomings, makes a most interesting historical figure. Passionate visionary democrat and slaveholder at the same time, I would give nearly anything to spend one hour's conversation with Jefferson! He is one of those Enlightenment intellects - so rare today! - that can move from politics to art and architecture or science; he might write excellent political philosophy one moment, and then wax eloquent about love and loss or the nature of friendship the next. I believe one of the most important explanations for why the United States has enjoyed such relative prosperity and good fortune so far is that geniuses like Jefferson helped build the initial national edifice which has stood strongly against the inclement winds of change and test of time. The written correspondence of Thomas Jefferson across his lifetime comes to fill several volumes and contain many gems of human insight and political prophecy. The below letter to Roger C. Weightman was Jefferson's last, declining an invitation to travel to Washington, D.C., to attend a celebration commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of American independence. Jefferson was too ill to attend, but he found the right words, as usual, to express the significance of the occasion. Fifty years after writing the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson could say:"All eyes are opened, or opening, to the rights of man."

Thomas Jefferson to Roger C. Weightman

Monticello, June 24, 1826Respected Sir, -- The kind invitation I receive from you, on the part of the citizens of the city of Washington, to be present with them at their celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of American Independence, as one of the surviving signers of an instrument pregnant with our own, and the fate of the world, is most flattering to myself, and heightened by the honorable accompaniment proposed for the comfort of such a journey. It adds sensibly to the sufferings of sickness, to be deprived by it of a personal participation in the rejoicings of that day. But acquiescence is a duty, under circumstances not placed among those we are permitted to control. I should, indeed, with peculiar delight, have met and exchanged there congratulations personally with the small band, the remnant of that host of worthies, who joined with us on that day, in the bold and doubtful election we were to make for our country, between submission or the sword; and to have enjoyed with them the consolatory fact, that our fellow citizens, after half a century of experience and prosperity, continue to approve the choice we made. May it be to the world, what I believe it will be, (to some parts sooner, to others later, but finally to all,) the signal of arousing men to burst the chains under which monkish ignorance and superstition had persuaded them to bind themselves, and to assume the blessings and security of self-government. That form which we have substituted, restores the free right to the unbounded exercise of reason and freedom of opinion. All eyes are opened, or opening, to the rights of man. The general spread of the light of science has already laid open to every view the palpable truth, that the mass of mankind has not been born with saddles on their backs, nor a favored few booted and spurred, ready to ride them legitimately, by the grace of God. These are grounds of hope for others. For ourselves, let the annual return of this day forever refresh our recollections of these rights, and an undiminished devotion to them.

I will ask permission here to express the pleasure with which I should have met my ancient neighbors of the city of Washington and its vicinities, with whom I passed so many years of a pleasing social intercourse; an intercourse which so much relieved the anxieties of the public cares, and left impressions so deeply engraved in my affections, as never to be forgotten. With my regret that ill health forbids me the gratification of an acceptance, be pleased to receive for yourself, and those for whom you write, the assurance of my highest respect and friendly attachments.

Th. Jefferson

ANOTHER POINT OF VIEW...

"Why do so many among us continue in words and deeds to ignore, insult and challenge the unforgettable words of Thomas Jefferson...?""Happy Independence Day America!"

by Frank Sinatra