Dante Alighieri's inscription on the entrance to Hell.

The entrance to the feared death camp of Auschwitz, author-psychoanalyst

Viktor Frankl's home as prisoner of conscience of the Third Reich.

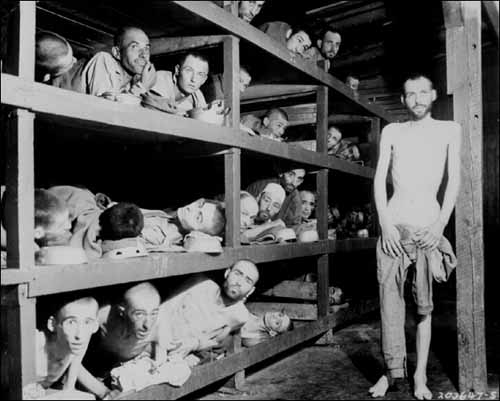

We stumbled on in the darkness, over big stones and through large puddles, along the one road running through the camp. The accompanying guards kept shouting at us and driving us with the butts of their rifles. Anyone with very sore feet supported himself on his neighbor's arm. Hardly a word was spoken; the icy wind did not encourage talk. Hiding his hand behind his upturned collar, the man marching next to me whispered suddenly: "If our wives could see us now! I do hope they are better off in their camps and don't know what is happening to us." from Man's Search for Meaning

by Viktor FranklARE YOU PRONE TO DESPAIR?

I highly recommend this book for anyone who questions life and wonders if it has any meaning or value. Frankl's reason for writing his life affirming book:"I had wanted simply to convey to the reader by way of concrete example that life holds a potential meaning under any conditions, even the most miserable ones. And I thought that if the point were demonstrated in a situation as extreme as that in a concentration camp, my book might gain a hearing. I therefore felt responsible for writing down what I had gone through, for I thought it might be helpful to people who are prone to despair."

DR. FRANKL ASKS HIS PATIENTSfrom preface to Man's Search for Meaning by Gordon W. Allport

"...in one life there is love for one's children to tie to; in another life, a talent to be used; in a third, perhaps only lingering memories worth preserving... As a long-time prisoner in bestial concentration camps he [Viktor Frankl] found himself stripped to naked existence. His father, mother, brother, and his wife died in camps or were sent to gas ovens, so that, excepting for his sister, his entire family perished in these camps. How could he - every possession lost, every value destroyed, suffering from hunger, cold and brutality, hourly expecting extermination - how could he find life worth preserving?"

Even in the degradation and abject misery of a concentration camp, Frankl was able to exercise the most important freedom of all - the freedom to determine one's own attitude and spiritual well-being. No sadistic Nazi SS guard was able to take that away from him or control the inner-life of Frankl's soul. One of the ways he found the strength to fight to stay alive and not lose hope was to think of his wife. Frankl clearly saw that it was those who had nothing to live for who died quickest in the concentration camp.

"He who has a why for life can put with any how."

Frederick Nietzsche

Frankl wrote the following while

being marched to forced labor in a Nazi concentration camp:That brought thoughts of my own wife to mind. And as we stumbled on for miles, slipping on icy spots, supporting each other time and again, dragging one another on and upward, nothing was said, but we both knew: each of us was thinking of his wife. Occasionally I looked at the sky, where the stars were fading and the pink light of the morning was beginning to spread behind a dark bank of clouds. But my mind clung to my wife's image, imagining it with an uncanny acuteness. I heard her answering me, saw her smile, her frank and encouraging look. Real or not, her look then was more luminous than the sun which was beginning to rise.

A thought transfixed me: for the first time in my life I saw the truth as it is set into song by so many poets, proclaimed as the final wisdom by so many thinkers. The truth--that love is the ultimate and the highest goal to which man can aspire. Then I grasped the meaning of the greatest secret that human poetry and human thought and belief have to impart: The salvation of man is through love and in love. I understood how a man who has nothing left in this world may still know bliss, be it only for a brief moment, in the contemplation of his beloved. In a position of utter desolation, when a man cannot express himself in positive action, when his only achievement may consist in enduring his sufferings in the right way--an honorable way--in such a position man can, through loving contemplation of the image he carries of his beloved, achieve fulfillment. For the first time in my life, I was able to understand the words, "The angels are lost in perpetual contemplation of an infinite glory."

In front of me a man stumbled and those following him fell on top of him. The guard rushed over and used his whip on them all. Thus my thoughts were interrupted for a few minutes. But soon my soul found its way back from the prisoners existence to another world, and I resumed talk with my loved one: I asked her questions, and she answered; she questioned me in return, and I answered...

My mind still clung to the image of my wife. A thought crossed my mind: I didn't even know if she were still alive, and I had no means of finding out (during all my prison life there was no outgoing or incoming mail); but at that moment it ceased to matter. There was no need to know; nothing could touch the strength of my love, and the thoughts of my beloved. Had I known then that my wife was dead, I think that I still would have given myself, undisturbed by that knowledge, to the contemplation of that image, and that my mental conversation with her would have been just as vivid and just as satisfying. "Set me like a seal upon thy heart, love is as strong as death."

Viktor Frankl

Man's Search for Meaning

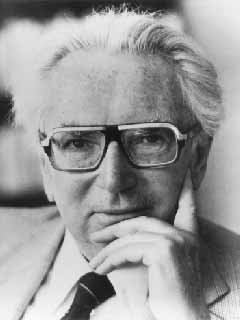

Both a concentration camp prisoner and world-respected author and psychotherapist in his lifetime, Viktor Frankl writes the following advice about happiness:

"Again and again I therefore admonish my students in Europe and America: Don't aim at success - the more you aim at it and make it a target, the more you are going to miss it. For success, like happiness, cannot be pursued; it must ensue, and it only does so as the unintended side effect of one's personal dedication to a cause greater than oneself or as the by-product of one's surrender to a person other than oneself. Happiness must happen, and the same holds for success: you have to let it happen by not caring about it. I want you to listen to what your conscience commands you to do and go on to carry it out to the best of your knowledge. Then you will live to see that in the long-run - in the long-run, I say! - success will follow you precisely because you had forgotten to think about it."

Of course, the important part is the "...in the long-run..."

A great man has left the earth; let us not forget him or his message.

Rest in peace Viktor Frankl!Viktor Frankl at Ninety: An Interview

by Matthew ScullyVIKTOR FRANKL, RENOWNED AUSTRIAN PSYCHIATRIST, DEAD AT 92

3 September 1997

Web posted at: 23:37 CEST, Paris time (21:37 GMT)

VIENNA, Austria (AP) Viktor E. Frankl, author of the landmark "Man's Search for Meaning" and one of the last great psychotherapists of this century, has died of heart failure. He was 92. Frankl died Tuesday and his funeral already has been held, the Austria Press Agency reported today, citing the Vienna Viktor Frankl Institute. It gave no further details.

"Vienna, and the world, lost in Victor Frankl not only one of the most important scientists of this century but a monument to the spirit and the heart," said Vienna Mayor Michael Haeupl.

Frankl survived the Holocaust, even though he was in four Nazi death camps including Auschwitz from 1942-45, but his parents and other members of his family died in the concentration camps.

During and partly because of his suffering in concentration camps, Frankl developed a revolutionary approach to psychotherapy known as logotherapy.

At the core of his theory is the belief that humanity's primary motivational force is the search for meaning, and the work of the logotherapist centers on helping the patient find personal meaning in life, however dismal the circumstances may be.

Frankl's teachings have been described as the Third Vienna School of Psychotherapy, after that of Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler.

In "Man's Search for Meaning," which has sold approximately nine million copies worldwide and been translated into twenty-three languages. The Library of Congress called the book one of the ten most influential books of the twentieth century. Frankl said: "There is nothing in the world, I venture to say, that would so effectively help one to survive even the worst conditions as the knowledge that there is a meaning in one's life."

According to logotherapy, meaning can be discovered by three ways: "(1) by creating a work or doing a deed; (2) by experiencing something or encountering someone; and (3) by the attitude we take toward unavoidable suffering," he wrote.

"We must never forget that we may also find meaning in life even when confronted with a hopeless situation," he insisted, a theory he gradually developed as a concentration camp survivor.

"As such, I also bear witness to the unexpected extent to which man is capable of defying and braving even the worst conditions conceivable," he wrote.

Viktor Emil Frankl was born in Vienna on March 26, 1905. His father worked his way up from a parliamentary stenographer to director at the Social Affairs Ministry. As a high school student involved in Socialist youth organizations, Frankl became interested in psychology.

In 1930, he earned a doctorate in medicine and then was in charge of a ward for the treatment of female suicide candidates. When the Nazis took power in 1938, Frankl was put in charge of the neurological department of the Rothschild Hospital, the only Jewish hospital in the early Nazi years.

But in 1942, he and his parents were deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp near Prague.

Frankl returned to Vienna in 1945, where he became head physician of the neurological department of the Vienna Polyclinic Hospital, a position he held for 25 years. He was a professor of both neurology and psychiatry.

Frankl's 32 books on existential analysis and logotherapy have been translated into 26 languages. He held 29 honorary doctorates from universities around the globe.

Starting in 1961, Frankl held five professorships in the United States at Harvard and Stanford Universities as well as at universities in Dallas, Pittsburgh and San Diego.

He was awarded the Oskar Pfister prize of the American Society of Psychiatry, as well as honors from several European countries.

Frankl taught regularly at Vienna University until he was 85 and was an avid mountain climber. He also earned a pilot's license at 67.

He is survived by his wife, Eleonore, and a daughter, Dr. Gabriele Frankl-Vesely.

![]()