author George Weigel

"Pope Is the Embodiment of Transformed Humanism"

by George Weigel

Pope John Paul II's visit to Cuba is, from his point of view, a pastoral pilgrimage aimed at strengthening the Catholic Church for whatever future lies ahead of it. The Cuban government, for its part, invited the pope as part of its effort to reintegrate Cuba into the life of the Western hemisphere. Immediate interests, ecclesiastical and political, will be in play throughout the week. But if we widen the analytic lens, the papal pilgrimage looks rather more dramatic. For this will be perhaps the final act in the great ideological drama of the 20th century, the conflict between atheistic humanism and Christian humanism. Christianity entered the ancient world proclaiming the liberation of humanity from the clutches of fate through the power of a creating, redeeming God. Atheistic humanism, a genuine novelty when it emerged in the 19th century, insisted that the opposite was true: God was a yoke, not a liberator, and humanity would be redeemed by its own heroic efforts to perfect the world. This vision of human self-redemption so permeated European intellectual elites that, 100 years ago, it was widely agreed that the 20th century would see religion withering away. A maturing humanity would put aside its childish need for the fantasy called "God" and grow up.

Communism was one expression of atheistic humanism. As it worked itself out historically, communism became many things: a form of revolutionary politics, an economic model, a method of social control. Socially, economically, indeed humanistically, communism was a catastrophic failure. But why is that so hard for some to admit?

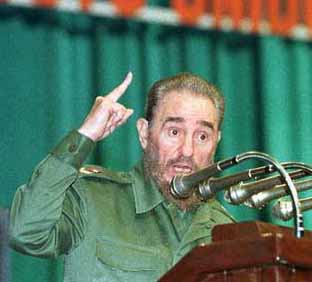

Perhaps it has something to do with the fact that communism retained the formal aspects of a religion. It had a doctrine of salvation and a theory of the "last things:" redemption through the dictatorship of the proletariat, which would mark the end of history. It had rituals, such as May Day and party congresses. It had an ethic: The revolution justified the means to its accomplishment. It even had an apostolic succession by which leaders legitimized their power; in Cuba's case, the orthodox line ran from Marx to Lenin to Castro. Despite its manifold failures, communism remained powerfully attractive, especially to intellectuals, because it addressed the enduring human need for redemption in a quasi-religious way.

Communism's collapse has forced the question of whether atheistic humanism isn't a contradiction in terms. Its intentions may have been noble, but a humanism that rejects God and scorns a transcendent horizon for human aspiration seems condemned to turn on itself. A world without windows or doors becomes suffocating, disorienting and dehumanizing. That was the world of Lenin's Lubyanka Prison and Stalin's Gulag Archipelago. That is the world from which Cubans have fled for almost four decades.

G.K. Chesterton used to say that when a man ceased to believe in God, he didn't believe in nothing, he believed in anything. Communism illustrates the point nicely. Communism began by affirming the human possibility in history; it ended up building history's most lethal slaughterhouses and justified them in the name of human redemption. That was a lie, but it wasn't a bald lie. It was a lie based on a delusion. When a man stops believing in God, he really will believe anything.

John Paul II comes to Cuba as the embodiment of an alternative humanism, Christian humanism. Dismissed as an absurdity 100 years ago, Christian humanism is one of the most powerful culture-shaping forces in a world on the edge of a new millennium. As articulated by John Paul II, it was instrumental in the collapse of European communism, in Latin America's transition to democracy and in the Philippines' "People Power" revolution. In each, Christian humanism defeated the often overwhelming material power of its opponent. Why? Because a vision of human dignity rooted in man's creation by God and redemption by Christ proved stronger than an ultramundane conception of the human person, human community and human destiny.

Atheistic humanism claimed that Christianity's God was alienating and disempowered human beings. The Christian humanism that John Paul II will preach in Cuba has disproved that claim empirically. Christian humanism is liberating; biblical faith makes a genuine freedom possible. That will be one of the great truths of the 21st century. Meanwhile, the 20th draws to a close with the list of signatories growing longer on atheistic humanism's instrument of surrender.

George Weigel, a Senior Fellow of the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, is Writing a Biography of Pope John Paul II