I have written hundreds and hundreds of college recommendation over the past fifteen years.

Each fall the task of writing these letter has always been above and beyond the teaching and grading of my Advanced Placement students in public school classes that were significantly larger in number than the twenty six the College Board urged. (My principal would just laugh if I told him the College Board recommends no more than 26 students per AP class. I would say the average class size was 37.) Writing letters of recommendation was not officially part of my job description, but it was something unofficially expected of teachers, especially those who taught Honors or AP classes, and especially teachers of high school juniors.

There was a time at the beginning when I was excited to write such a letter. I remember writing a letter of recommendation to Harvard University on a Friday night. I went to my classroom in the dark on a Friday night to do this! It was just me and the janitors. (Currently married and with children, this is unthinkable now.) I remember a letter of recommendation that came due first thing on January 1st, and I wrote the final part of it and sent it off at a New Year’s Eve Party. I finished it on the computer in the home office of the host, filing it electronically just before midnight with everyone cheering outside.

I was honored to write these letters. I took them seriously. I invested myself in them.

But the novelty wore off after a few years. It became work. Hard work. As is all writing that seeks to be well done.

“Can’t you just fill out a form letter?” my father would ask me. “This should’t have to take you so many hours!” But the universities wanted specific anecdotal evidence as to why this particular student would make a good candidate for next year’s freshman class. The stronger students would get three and four page letters, single-spaced, written by me. I would spend hours writing drafts. There could be no short cuts.

And these young adults, I would reflect, were worth it. I had pages and pages of positive things to say about them. They had earned that letter.

But it was more work. A lot more work. And year after year I came to grow resentful of them.

Not resentful at my students who came asking for me to write the letter.

But to the universities, and to my own employer, who would just add more work to an already overworked high school teacher. “Just smile and do it for the kids!” they always seem to say.

And the letters of recommendation is one of the reasons I no longer teach those classes. I would write some thirty letters per year.

The “prestigious” universities are the ones that require the letters. The MITs, Yales, Browns, Columbias, Dukes. They also have personal interviews students must attend, wishing to impress alumni volunteers who direct them. High school applicants also write several personal statements, fill out lengthy applications, and collect coursework to present. Probably there are other tasks I don’t know about.

One thing has been crystal clear to me: applying to college is a nightmare. And it is the worst for the best students.

It was bad when I was in high school. Now it is worse. And it is one of those problems where it got worse little by little until, almost imperceptibly, it had become way worse than anyone wanted it to be. It is like the frog in the cauldron who little by little allows the water to get warmer without jumping out of it, and then suddenly, the water is boiling hot, it is too late to get out. and that frog is boiled.

Applying to fourteen or fifteen universities. Costing thousands of dollars in application fees. Spending months getting all the materials together. Waging a full-time campaign to get into Princeton starting no later than seventh grade. (No wonder such Princeton students often go on to work on Wall Street as pit bull lawyers.)

And then, after all that work, the most selective schools turn almost everybody down.

It is as if it is worth giving a kidney to gain entrance to an Ivy League university.

And then, perchance, if one is lucky, the clouds might part and the finger descend down from the sky and point to that lucky high school senior — “You are in! You are the one! We will allow you a precious space in our freshman class (if you pay tens of thousands of dollars for it).”

Congratulations, you got into Stanford. It is “easy street” after that, supposedly.

As if life were quite that simple.

I was thrilled when my first student got into Harvard. (Maybe my heartfelt letter had helped him get in.) I was happy when my second student got into Harvard. I got up from my desk both times and gave those kids a big hug.

But I had come to be jaded by the whole process. By then I was thinking how I could protect my own daughters from all this nonsense. Much of the trying to get into college experience I found to be positively harmful to young people when in high school.

Well, that felt good to get off my chest.

Now to the point of this blog posting.

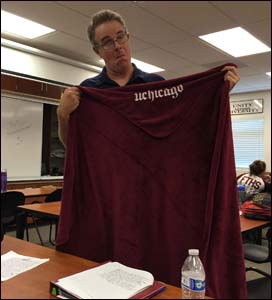

Today I got a package in the mail from the University of Chicago.

Curious, I opened it up and it was a plastic case with a blanket inside. It was accompanied by a kind letter from James Nondorf. He thanked me for taking the time to write letters of recommendation for students applying to the University of Chicago.

I was flabbergasted.

After literally writing hundreds of letter to dozens of universities over fifteen years, this was the first concrete sign of a “thank you” from one of them.

It was a nice blanket. Red. With a University of Chicago logo. But I don’t think any such small token of thanks costs a university much money. And it was not really about the blanket, anyways.

It was the gesture. That they took the time to make the gesture. Respect for one’s (uncompensated) time and effort.

It is one of those small gestures that can make a big difference.

Thank you, John Nondorf.

After all these years, the gesture is much appreciated!

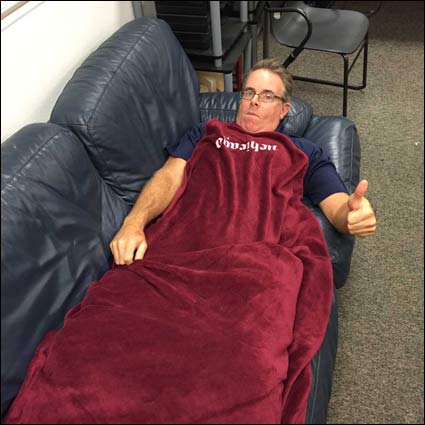

P.S. The blanket I used to sleep with occasionally on my classroom couch dissapeared over summer vacation. I needed a new blanket!

And now I have one.