ON THE DEATH OF MY MOTHER

"My mother survived for another fourteen months, although the doctors gave her only two."

![]()

"I know our culture does us a disservice when it hides death in hospitals and refuses to talk about it, as if it were an unpleasant and inconvenient business best ignored. I know life is not forever, that death is a natural part of life, our common fate one and all."

![]()

They say that to die is as important as to be born, that the one is merely the completion of the other – and that death is not merely the end of life, but is a crucial part of life. Having watched my mother macerate and die of cancer, I know this to be true.

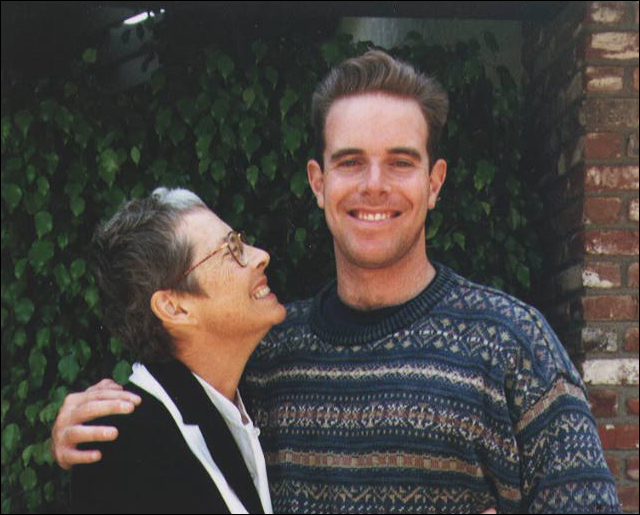

It began in the fall of 1995 when my mother complained of pain in rib cage for some weeks before she finally saw a doctor. The tumor that the subsequent X-rays discovered in my mother’s left lung was the size of a softball, a giant dark circle in the light area of my mother’s lung in the X-Ray photos, and emergency surgery was immediately scheduled to remove the entire lung and tumor inside it. Subsequent tests, however, showed that the cancer had spread from the lung into my mom’s liver, bones, and lymph node system. The cancer was “Stage 4” and removing the tumor would not help; the cancer had already spread. The doctors privately told me there was no hope, that my mother might last four more months. My brother was in San Francisco at the time, and my sister was teaching English in the jungles of Indonesia; besides my mother, it was just my father and I in that grim hospital room on that dreadful day when test after test came back with the worst possible results.

My mother cried and cried and made many phone calls. By the end of the day, however, she had stopped crying; she seemed exhausted, and she simply wanted to go home. The sense of haste and emergency of the previous days was gone; there was nothing modern medicine could do for my mother, and the hospital released her. The chemotherapy would start the next week. I wheeled her out of the hospital exit in a wheelchair as we waited for my father to swing the car around front. It was dark out by then. The scene was surreal. It seemed like a movie; this kind of day only occurred in movies. We did not talk. We were numb. The calm after the storm.

Earlier that day my father and I finally had gotten a moment away from my mom in the hospital cafeteria and he had cried like a baby with his face in his hands. I put my arm around him, oblivious to all the stares of everyone else in the cafeteria at us. My world was crumbling, with my mother’s illness, but my father’s entire universe was falling utterly to pieces right in front of him, with his wife threatened. I was torn between being strong for my father and feeling my own grief. “I am the oldest child; it is my job to be strong; and I cannot fall apart myself. What would my younger brother and sister think if the oldest fell apart? If my father were incapacitated, it is my job to lead.” So I thought at the time. And so I acted for more than a year.

My mother survived for another fourteen months, although the doctors gave her only two. I always admired my mother for proving those horrible doctors wrong. She deteriorated slowly but certainly, the chemotherapy slowing but not stopping the spread of the cancer. Finally, the inexorable march of the tumors reached the brain and a small army of tiny tumors grew there until the pressure of swelling tumors depressed vital parts of the brain dealing with breathing and heart beat, and my mother finally died.

I have never seen anything as beautiful and touching as my father caring for my mother as she retreated into a sort of second infancy. First, she lost the capacity to speak and think clearly. Then my mom could no longer walk without help, and finally she could not walk at all. By the end she had shriveled up, could recognize nobody, and had to be washed and fed as if she were a baby. My father would wake up in the morning and wash her body. Although she could not recognize anyone, my father would talk to her lovingly as he brushed her hair: “Good morning, my darling! You look so beautiful today!” He brushed her teeth. He changed her diapers. This was marriage: “until death do us part.” It was the most romantic thing I have seen.

The next fourteen months brought many highs and lows for my family, but we moved closer together for comfort and strength: there were some incredibly beautiful scenes during that time, the pain and the love all mixed up together in emotionally superheated moments. There was, for example, the thunder storm that came out of nowhere as we dined on the patio, with my mom’s poignant reflections on the process of living and dying punctuated by lightning. The time was precious, being limited; life seemed so much more intense than usual. There were many laughs, and a parade of relatives flying into town for extended visits and the saying of final “goodbyes.” It is during such times that one truly understands what “family” means. Love surrounded my mother like a halo.

My mom died in our house, surrounded by her family, in her own bed – with her favorite rose bushes just outside her bedroom window. There at the bitter end her breathing had a horrible shrieking noise, as by instinct her body labored to live on against all odds: life struggled hard against death, at the end. It had been weeks since my mother had been recognizable to me, and I wanted it to end: “Blessed death, come and bring her peace!” Everyone knew the end was near, and my brother flew down to Orange County from San Francisco on Halloween Eve of 1996: some twenty minutes after he arrived, my mother died. It was as if she somehow and somewhere recognized that my brother had arrived and that the entire family was now assembled outside her room, and so she could finally let go. When they emerged from her room and told us our mother was dead, my brother almost collapsed: I held him up, my arm around his waist. I am the oldest brother, after all.

My mother’s friends cleaned and laid out her body, with a scarf tied around her head to keep her jaw from dropping open, and they finally let us in to see her. My mother was transformed: she looked like my mother for the first time in weeks, in death. Her face and facial muscles were no longer unnaturally contorted by brain damage. My mom was at peace; candles were lit around her body. Her favorite religious icons surrounded her: the rosary from childhood, a picture of the Virgen de Guadalupe, her miniature statue of St. Francis. The scene in that room was more peaceful than it had been for a long time. My mother struggled in the pain of her birth, I am sure, and she struggled in the trial of death; the circle of life had been completed. Her death had been such an important part of her life, and I learned this with my own eyes.

My mother died at home, surrounded by friends and family, not in some impersonal hospital surrounded by strangers. Her friends cleaned her body, not professionals employed for the task. She died next to her beloved rose bushes, not next to antiseptic white hospital walls. With as much courage and strength as she could muster, she died as well as she could. She made a good death, something that can bring honor to an entire life.

I know what it means to watch your mother die. I know what it means to have a mother who, when she gave me life and helped me to live outside the womb, taught me from the very first days of my life all the way up until and beyond her last breath -- when she taught me what it means to die, so that perhaps one day I can also do it well.

I know our culture does us a disservice when it hides death in hospitals and refuses to talk about it, as if it were an unpleasant and inconvenient business best ignored. I know life is not forever, that death is a natural part of life, our common fate one and all.

I know that this knowledge, strange as it seems, gives me a certain sense of peace.

"They say that to die is as important as to be born, that the one is merely the completion of the other – and that death is not merely the end of life, but is a crucial part of life."