Milken Community High School

of the Stepen S. Wise Temple of Los Angeles

Bel Air, California

![]()

1997-2000

I arrived to my job interview at Milken Community High School in August 1997 not taking it too seriously, as I was on the verge of accepting another teaching position at the time. I figured I would quickly check out Milken just to be polite, but I was immediately impressed: Milken was located on Mulholland Blvd. in Bel Air just above the San Diego Freeway, along with a slew of other expensive private schools. After the interview, I stood there next to my car in the parking lot thinking to myself. What to do? I had already almost accepted a teaching somewhere else.

I was initially moved to reject out of hand even the possibility of working at Milken, after I learned the school had been recently re-named for a convicted felon. What does that say about the place?!? I wondered to myself incredulously. Would I be embarrassed to say the name of my school to friends and acquaintances? But after the interview and having seen the place with my own eyes, I had softened in my approach.

It would be nice to spend my days up among the sage brush in the tranquil Sepulveda Pass, I thought to myself. There were no sounds other than the shouts of children playing and the desert winds blowing through the canyons. Much different than my previous work environment near downtown Los Angeles, I reflected. The school sported scads of computers, and I could tell students would be of high caliber: something like 99% of their students passed their AP exams. Students here will most likely take their education seriously (in direct contrast to my last school) if their parents are paying serious cash for it! I thought. The school was Jewish, and I had grown up surrounded by Jews. It would be like returning to a comfortable known world after long absence! I told myself. True, the school had a dubious namesake, but the place looked so good I didn't care if it was named after Lucifer himself.

It did not take long for me to make a decision, and I was on the job two weeks after that first interview. And happy I was at Milken Community High School the three years I worked there, teaching the humanities to 7th and 8th graders. Milken was not the end of my journey, but it was a key gestating period, a transitional stage.

But let me let my letter of resignation speak for me:

March 10, 2000

Dear Rennie,

After much thought I have come to the conclusion that this will be my last year at Milken Community High School. It pains me to write this letter, as I have enjoyed being a member of the faculty at Milken and have worked hard to do my job as well as possible. (With all modesty I can say that no teacher has worked harder than me at Milken over these past three years. Some have worked as hard -- but none harder.) I have decided to move on for reasons having more to do with the nature of the environment in which Milken is located rather than the school or nature of the job itself. Let me briefly explain.

I started my teaching career working in the Los Angeles city schools which hardly deserve to be called "schools." Many of the students there were illiterate, and too many had long since been taught by being passed from grade to grade with little or no effort that an education involves nothing more than occupying a desk year after year without doing anything. The staff there had resigned themselves to doing the best they could and simply surviving day to day. Milken was very different, and it has been a privilege and an honor to teach here: I knew myself to be in a place devoted to learning and the life of the mind, felt myself to be one more scholar (in my own humble way) in a learning community. From the very beginning I looked around me and watched students straining and complaining under the weight of two or more hours of homework every night. I watched teachers pushing, pleading, cajoling, and threatening their students to do better and to achieve more. Students are challenged at Milken to take ideas seriously and admonished to meet high teacher (and parent) expectations: that is what makes an education profound -- what a true education costs the heart. Leaving the L.A. city schools, I was not sure if teaching was for me. As I leave Milken, I cannot envision doing anything else.

Milken is where I learned to teach. Teaching at Berendo was so grim and crushingly depressing that I could hardly make it to 3:30 p.m. and the end of the school day. When off-duty, I simply recovered. Conversely, I worked non-stop at Milken -- evenings, weekends, vacations. I enjoyed work, and I enjoyed the students. I woke up every morning eager and enthusiastic to teach. I put countless hours into making sure my lessons were engaging, motivating, and challenging in the belief that a good teacher is first and foremost a demanding one. I made myself available for students who needed extra help. I treated each child with respect and truly believed every child could learn. I told my students I would push them hard in my class. I promised them they would sweat, bleed, and cry over the course of the year; but I also promised I would not ask them to work harder than I myself was willing to work. If as the teacher I would play the benign tyrant, students knew it was more a partnership than a dictatorship. We would learn together.

And the kids they made me laugh! I thought they were clever, funny, and (for the most part) very hard-working. They were enthusiastic and curious, and foreign lands and new knowledge outside their understanding excited and interested them. They wanted to learn, and they wanted to be taught. The focus was on learning, and the students were there to learn. They were highly literate, filled with passion and curiosity. Alive! If I asked a class how many of them wanted to write a book one day, almost half the hands would go up. Many of them would. They were confident in their skills and abilities, and they had reason to be. It was an ideal setting for a teacher.

And I enjoyed it! I developed deep connections and lasting friendships with many of my students that are important to me today to this day. While working at Milken I often spent my lunches and breaks outside with the students instead of inside with the other teachers. When in the greater Los Angeles basin nowadays, I try to get together and touch bases with ex-students. We exchange e-mails and speak honestly and to the point. I can hardly overestimate how important this is to me. Other adults invest in the stock market or real estate; I invested in my students. As the years pass and former students mature into thoughtful young adults, this investment pays off richly and handsomely. It makes all the frustrations and sacrifices of being a teacher worth it. It is an investment of enduring, enriching value. It is an investment not of money but of time and love. "The only gift is a portion of thyself," posited Ralph Waldo Emerson. This was the path I chose to walk. A life devoted to duty and service. What could be better?

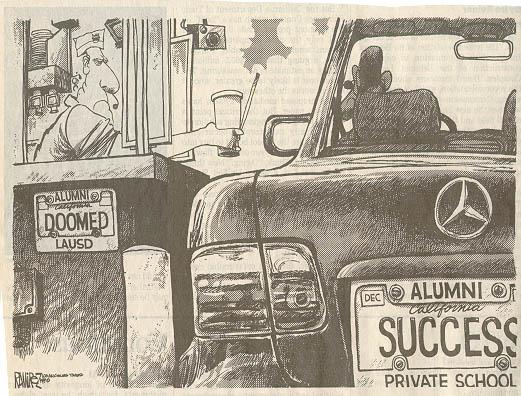

MONEY IN THE BANK

Many volunteer to tell me what could be "better." Friends and family, for example, point out the infamously low salaries and inferior working conditions of teachers. They remind me of the importance of money in the bank and material resources at one's beck and call. This is good solid advice, as it costs so much to live today and money is important in so many ways. Just to cover the bare necessities costs a lot, and wealth in of as itself confers power and respect upon a person, even if they be a scoundrel in all other ways. "Money talks and bullshit walks," goes the saying, as "gold is a language spoken everywhere." Wealth is crude naked power; poverty is always a burden and a weakness. As I get older I see this more clearly. Because of my choice in career money is always tight; I watch my bank account like a hawk. Somehow, I always get by.

I am not paid starvation wages, and in the eyes of many poor people my income is generous; but I see clearly how with my education and skills I could make much more money in a slew of other jobs for which I am eminently qualified. My peers almost to a person occupy those "other jobs." (Do I err in not joining them? Have I made a mistake? Regret rears its ugly head.) Back in college I thought the best and brightest of my friends and acquaintances would go on to become poets and philosophers. Instead they attended MBA school and went into business. When you are young they tell you love makes the world go around. Later on you realize trade and taxes more properly fulfill that function. These hard realities began to come into focus at this stage of my life, as my peers and myself entered our 30's and began marrying, buying homes, and having babies - or didn't. (I was single at the time with no prospects for marriage.) Idealism didn't put food on the table or a roof overhead - nor did it provide for a "comfortable" life. You can say all you want about ideas and ideals; but at the end of the day some people live in nice large houses and other don't. (I lived not even in a humble house but rented an apartment.) Some people work hard to feather their nests and live comfortably while others struggle. This is how I think in my darker moments.

It is then that I wonder at what a sucker I was to become a teacher. I wonder at what a sucker I am to remain a teacher. It is, narrowly speaking, not in my best "interests." I could, after all, leave the profession and double my income overnight. But then I think of the cold call of duty and service. A life dedicated to something larger than oneself. I feel reassured. But the tension is always there. Doubts besiege me. I fight them.

One can be happy as a teacher if one embraces a different value system than most in a capitalist economy. But in being "different" one can also feel alone, even betrayed. I often feel, for example, like a stranger in my own country. This is an unpleasant sentiment. I feel alienated and isolated. That is painful. The world struggles and the years pass by and good and evil clash in the public arena, while I am stuck in my classroom - infantalized! The grown-ups in the real world make the decisions while the students in school are ignored; and as a teacher in a school, one feels like a student. Ineffectual and impotent, one finds oneself relegated to the sidelines. Am I a fool? Am I wasting my life? Or could I at least make better use of it? Should I leave teaching? I could do some other job. But then I think about the enormous influence teachers have on the future. I reflect that teachers have more long-term power than presidents or generals: a dynamic teacher never knows where his influence will end. And despite everything, I enjoy the job; I work almost non-stop; and I am happy doing so.

So I stick with teaching. For better or worse, it is the path I have chosen. Nobody forced me to become a teacher; I chose the profession knowing full well its sacrifices. But as teaching can be a hard life with few external rewards and many frustrations, hopefully it will be one without remorse or regret. I don't wish to sink into bitterness and sullen resentment, as do many teachers I know; the last thing I want to do is slide into the role of a martyr, unless it is quite unavoidable. So I try to ignore the disappointments of my chosen profession and focus instead on its many satisfactions. Most people focus on the acquisition of wealth because that then leads to access to so many other things - fame, fortune, jet airplanes, beautiful women, luxury houses, etc. It is supposed this leads to "happiness" and "fulfillment." I intend to amass a different form of "wealth." Only time will tell if the decision was worth it. The popular bumper sticker reads: "He who dies with the most toys wins." We shall see. T.S. Eliot advises us to live otherwise:

I say to you: take no thought of the harvest,

But only in proper sowing.I hold with Eliot. If the sowing be done true and well, then I will trust in the harvest. So it goes.

A WAY OF LIFE...

Slowly, subtly, almost against my will, and over a number of years, education became the center of my life; as some are called to the clergy, I found myself obliged to teach. It is hard to understand or explain exactly how this occurred. I had never thought to become a teacher when growing up. The idea, in fact, would have left me cold - if not horrified me! It still horrifies me, strange as it is to admit; I almost feel as if it has happened to someone else - happened against my will! But as Dr. Samuel Johnson claimed, "He has learned to no purpose, that is not able to teach." Teaching was for me not a job or a career but a vocation, a way of life. It was something to live for, something I needed. I was a thinking person, always had been since I was a kid. As an adult I would teach the glory and passion of the Renaissance, the sacrifice and heroism of the Civil War, or some other equally fascinating subject all day and then read more about it late into the night; if I did not need to feed, house, and clothe myself, I would have done it for free. Is there anything more fun or exciting than teaching Shakespeare's "Romeo and Juliet" to teenagers? I would almost pay for the privilege of doing so!

To live thusly, for me, is happiness. It is fulfilling. To participate in the ongoing story of humanity, to show the joy in the life of the mind, to explain to my students the past and how we arrived at where we are today, and then to leave for my students to take it from there into the future: it is a life worth living. So help me God.

************

But let's return to the specific situation at hand: my experience at Milken Community High School. Why then was Milken so different from Berendo? Why was I successful in the former, where in the latter I found mostly frustration? First of all, students at Milken came to school already knowing a certain amount of knowledge that teenagers need to know succeed in the world. They already knew about the ancient Pharaohs, certain of the works of Shakespeare, and the multiplication tables simply by what they absorbed informally at home. Students read competently and wrote proficiently, having grown up surrounded by print in households headed by professors, doctors, judges, etc. Many of these young people were already experienced world travelers and had imbibed from earliest mother's milk to last Friday's dinner table conversation a vast array of political banter, current events, and cultural history. The breadth of knowledge and complex literacy skills acquired by Milken students before they even stepped inside a classroom is what made them such fertile ground for a teacher's ministrations -- and in large part explained their very high academic achievement. 7th graders entered my class reading and writing at perhaps the 9th grade, and it was my goal that they should leave performing at the 11th grade. The kids hit the ground running fast, and I saw it as my job that they would accelerate. Take a look, for example, at the following units I developed:

Islam

Modernity

Flowers for Algernon

ChristianityDo you see what I mean?

Here and there I heard a few mumbled complaints that certain of my assignments smacked of college-level work, not middle school material; and they were right. I occasionally heard murmurs that the work was not "age appropriate" for 13-year olds and that I would "turn students off" to school by demanding what it was not "natural" for them to produce. But the students - after I taught myself ragged imparting to them the subject matter - did themselves and myself proud in performing admirably in their examinations: when challenged, they rose to the occasion. They sweated blood to try to understand difficult ideas, to understand the past and themselves; and I was often astonished at the insights these young adults made, the originality and precociousness of their thought. This was, in my opinion, what a proper education should be. If some people felt I demanded too much of young people in my classes, I suggest they demanded too little. (If students can and do perform the work, why tell them it is too "advanced" or "difficult" for them? I never told students my goal was for them to perform at the 11th grade level, after all!) If the difficulty of the assignments stretched and pushed students to their utmost, they could enjoy afterwards the satisfaction of having been able to achieve beyond their expectations. Is there anything that feels better?

The bottom line was this: on the first day of class, I solemnly promised my students I would endeavor my absolute best never to waste their time. They might not like me, my lesson plans, or my approach to the curriculum, but I would do my best to present subject material in as interesting and creative manner as I could. I would engage them; I would be prepared; I would hold up my end of the bargain. I would ask perfection from neither myself nor them, but I would come pretty close. (I asked students in my classes to raise their hand if they ever had a teacher who wasted their time. Everyone raised their hand and many chortled in angry affirmation. I myself had plenty of teachers who wasted my time. It was terribly frustrating!) After all the trauma and exertion from stressful in-class essays and arduous long-term projects, students at the end of the year could look back and feel a sense of accomplishment at having worked hard and learned. In the short-term students did not necessarily want to work their fingers to the bone completing challenging assignments. Often they wanted to have fun with their friends and goof off - such is often the nature of youth. But I reminded students why they were in school and why we gathered together everyday. I preached about actively attacking one's studies instead of passively letting school happen to you; in this I saw school as a metaphor for life. I talked about setting goals and having high expectations for oneself, both in school and in life. (Hence my work e-mail .sig file and class motto: "Non schola sed vita decimos!" We learn not for school but for life!) And I could see - through the pain, agony, and pleasure from triumphs and some defeats - a sense of accomplishment in the demeanor of each young person as they reflected in June about what they had been able to accomplish and learn since the previous September. This state of proud exhaustion was my goal for students from the very first moment they entered my class. The learning and the effort it exacted was, after all, the point of the whole venture. It was what a true education costs the heart - what learning at a deep level requires.

But I am not one of those who believe the path to learning must always be sweaty, painful, and rough, although sweat, pain, and roughness can never be entirely avoided. When I could see my students were exhausted and near the breaking point, then I would back off and have a pizza party in class and watch a movie. If I would intentionally push my students to the limit on occasion, I would then back off and let them relax and goof off. If we would work hard, we would play hard. (I considered it one of my most important tasks to watch carefully how tired my students were or were not, and then act accordingly.) And even if what we were studying was serious and important, there was always time for the usual give-and-take classroom banter of a teacher and students who genuinely enjoy each other's company and wit. My ideal was a severe gentleness towards my students who were not, after all, adults but budding teenagers; in retrospect, I was more indulgent of academic peccadilloes than I should have been or, indeed, had promised to be. If it is important as a teacher to have clear rules and to hold students and yourself accountable to them, it serves no higher purpose to become a martinet or a killjoy. I became a teacher more to teach than to scold, and it was easier and more natural for me to praise than to condemn. It was always about, if at all possible, having a positive attitude towards school and learning.

A POSITIVE ATTITUDE

In the end it is not about parental resources or educational level, access to computers, school board politics, pedagogical ideologies, or gender, racial, and ethnic considerations. In the end it comes down to one's attitude. It comes down to what is important and a priority for both teachers and students. I have worked at schools that no amount of money or resources would improve until and unless attitudes changed. And I have worked at schools where the students were so motivated to learn that even the least competent teacher in the world would be successful. Milken was such a school.

Attitude. The will to learn. The desire of students to learn, coupled with the desire of teachers to teach. All other concerned parties - parents, school administrators, politicians, clerisy, business elites, and community activists - were important only insofar as they supported learning which took place in the classroom directly between teachers and students. Nobody besides the teacher and students knows what happens in the classroom day after day: whether everyone slacks off or works hard, goes through the motions or tries in earnest, etc. No one knows if learning is taking place or not. Unless you were there constantly, you would not know. You can demand all you want and pass laws and administer standardized exams and require results, but it only means something if teachers and students act on it. Standardized tests (so popular nowadays) reflect student learning only in the very shallowest sense, and if one relies on testing to motivate and give meaning to an education one will encounter meager two-dimensional results, at best. A teacher (and the larger community) needs to stress the importance of becoming an educated person and explain (and exemplify) what that means in real life. Intellectual curiosity, critical thinking, self-discipline, and rock-solid work habits all combine to form a positive academic attitude; and as attitude dictates action, so actions result in learning or not. A positive attitude is the fount from which all further learning finds inspiration and sustenance.

A negative attitude in students or a teacher, in contrast, spells nothing but trouble. It means a teacher holding students hostage every day and boring them to distraction with inaction or fruitless action. It means students just giving the finger to the teacher and refusing to apply themselves. Regardless, it results in wasted time - hundreds or thousands of hours of wasted time, and even wasted years. It happens all the time. It is thus not only in Los Angeles or American schools but everywhere. Gratefully, I saw very little such wastage at Milken.

ELITE LOS ANGELES PRIVATE SCHOOLS

The average student at Milken had from a very early age traveled a select educational path, and it is important to take into account the larger social context of exclusive Los Angeles private schools. It was a process that began not long after the birth of a child. Parents surrounded their infants in the crib with the strains of Mozart, for example, modern science having told them that exposure to such music would lead to more synaptic connections in the rapidly developing brain of babies and consequently smarter children. Parents knew their children would soon have to compete against other kids for a limited amount of spots in kindergarten classes at competitive private elementary schools, and so they busied themselves building the blend of talents and skills that would enable their child to beat out the competition in securing one of the coveted spots in these schools: kids attended high quality preschools and were enrolled in as many extracurricular computer classes and early reading and math classes as schedules would allow. Having hardly having mastered rudimentary English vocabulary, kids underwent IQ tests as parents began the multi-pronged effort to pre-program their children towards academic success. The average Milken student had from earliest age been constantly engaged in this fierce fight to gain entry to the "right" schools: elementary school, middle school, and then high school. It was the same route no matter whether the child attended Milken, Wynward, Crossroads, Harvard-Westlake, Viewpoint, etc. You had to have the high test scores, the good grades, and the right recommendations to qualify at each step. It was not easy! There were as many kids on the waiting lists for these prestigious schools as there were enrolled. The competition was fierce!

But parents knew what it took to get their children into Yale. They knew what it took to become successful professionals such as themselves. They knew how competitive it was, how you had to wage a long, careful campaign to get into top-flight schools. A young person had to have everything together! Everything perfect! Not one false step! Parents were willing -- even anxious! -- to pay top dollar to make sure their child had this edge in life. Very early in life such a child learned to become committed, serious, disciplined, and goal-oriented. (If you ever wondered how a certain generic type - a Wall Street lawyer or an Hollywood film executive, for example - learns to go for the jugular, the key is in such an upbringing.) And as a young person you knew one mistake could cost you for a lifetime! Parents would do anything to avoid such a misstep. They would pay for tutors, educational psychologists, and extra classes at night and during summer to help their children grasp and master any curriculum not being covered in school. (If for whatever reason a teacher failed to teach the material, it meant a windfall for the tutors!) Even a slight slip in a child's grades could bring a flurry of worried phone calls to teachers. Expensive SAT prep courses were de rigueur. Such parents, understanding well the college acceptance game, knew how to work the system. As a teacher, these parents helped to provide me with students who would much more readily respond to my teaching. They were fertile fields in which I could plant bountiful crops. But it put a powerful pressure on a young person.

Teaching at Milken did have strong negatives. Worst among them were importunate parents on the phone treating you like the hired help, imperiously demanding you do whatever they wanted - now! ("I am paying $17,000 in tuition, and I am too busy to argue about it! Just do what I want!") Every morning I would check my phone messages with my fingers crossed; there were usually one or two messages waiting for me. ("Oh, God! Now what?!?" I would say to myself.) On the infrequent days when I had no voice mail I said a silent prayer of thanks ("Thank God!" I would sigh to myself silently.) Often the parents proved more tiring than the kids; 75% of all phone contact were the same parents mulling over the same issues. (One had the feeling they felt the problem would resolve itself if you talked about it enough. The problem more often than not revolved around a child who would not take responsibility for his/her situation and a parent who tried to cover for him/her. Such a parent is called an "enabler." It doesn't help.) It was the good, the bad, and the ugly.

At one end of the spectrum at Milken lay the educated, loving parents who would work with teachers instead of against them. It was always a pleasure to deal with such parents, and with them the teacher's word was law. This was America at its best. They were successful, decent adults who had worked hard to become educated, understood the importance of education, and involved themselves in their children's studies. Teachers and parents worked as a team to deliver a single message to young people: pay attention, learn, and achieve good grades in school. Students got the message loud and clear. There was no playing the one off the other, no weaseling your way from owning up to your grades. Everyone was on the same page, and there was nothing worse for a young person than appearing "dumb" in front of your peers and the adult world. In short, a powerful pressure to do well in school exerted itself on a student from all corners. Young people, in response, became goal-oriented and focused - not unlike their parents! They became driven but generous and kind-hearted; as students they performed well in excellent schools and enjoyed comparatively happy childhoods; and they would one day rise to positions of power and prestige in the most powerful country in the world. If you ever wondered how a Nobel Prize winner in physics or chemistry or mathematics managed to reach such amazing heights of learning and achieve stunning intellectual breakthroughs, it is often in just such a background. If you ever wondered how the United States continues to be the economic and technological engine of the world, look to students such as are found at Milken. The United States produces such people in large numbers. They make a difference.

On the other hand, unfortunately, one encountered the worst face of America: self-centered narcissists who thought the world existed to serve them. One came squarely face to face with the infamous "ugly American": the self-involved spoiled who thought they were the center of the universe. And they of course learned this at home, most often. And so at Milken Community High School I learned a basic life lesson: loud obnoxious parents produce loud obnoxious children. Simple enough.

And then there was also the question, Did I belong at Milken? Did I fit in? The answer was ambiguous, at best. I looked around sometimes and wondered what I was doing in an expensive Bel Air private school. Countless faculty meetings and professional reviews, documentation and paper work without end, and the very formal buttoned-down prep school demeanor. I half-waited for someone to figure out I didn't belong there and escort me off the grounds. At times I felt like a turd in a punch bowl. Not many years earlier I had been a hell-raiser getting in fist fights and enjoying them, etc. I had been an inveterate skirt chaser. But Milken could be a very pristine, air-brushed school. Parents paid good money to have their precious children protected from the baser elements. This was private school. Parents were happy to pay for it. But I was not by temperament an entirely pristine, air-brushed person; I had my rough edges. Certain parents would complain if I occasionally used even slightly off-color language in class -- clearly, this was not for me. There were relatively few other male teachers, and there was a subtle female essence in the air that if not alienating was not always welcoming or comfortable. All was psychology and nurturing and navel-gazing and "it takes a village to raise a child." Yuck. In ways large and small I was incongruent with my surroundings. The gap between how I had to act at work and how I preferred to act outside of work was unnaturally and unhealthily large. To keep the two separated proved tiring. The "fit" was not perfect.

There were cultural factors as well. Milken Community High School is a Jewish school and with time the sound of Hebrew prayers, the sight of the Israeli flag, the Holocaust again and again, and wars and rumors of war in the Middle East became tedious. I am not Jewish. I am not Israeli. Judaism, the nation-state of Israel, the Hebrew language, the politics of the Middle East - all this meant little to me. I am a skeptical humanist in the secular mold through and through; and the tribalism of blood, soil, and religion are anathema to me. I see Jerusalem, for example, not as the center of the earth and cradle of all that is good and meaningful but as a bleeding ulcer endangering the peace and stability of the whole world. My perspective was different. "Men never do evil so completely and cheerfully as when they do it from religious conviction," claimed Blaise Pascal. Exactly! I would transport the entire Middle Eastern region to the surface of Mars if I could, safely removing much wild-eyed fanaticism and danger from planet Earth and thereby making it a safer saner place. And even after fifty years nobody was in danger of forgetting the Holocaust wrought by the Nazis had ever happened. More likely, people were ready to give it some distance. What more can I say? I tired of looking down at my shoes as everyone else sang the traditional blessing in Hebrew (of which I understood not one word) before meals. The Israeli flag hung outside the school, but I was an American. What was I doing there? I had lived happily among and with Jews all my life, but being this closely involved with the Jewish community and religion was too much.And there was, finally, in my last year at Milken, an ugly unfortunate incident involving, of all things, my personal webpage. After explaining the importance of revising written work over and over again, I shared a piece with my classes that I had just written about a recently released movie. (I explained to students how I had revised that essay eight times before I posted it; I wanted them to know that as they were "writers" by virtue of taking my English class, so I was a writer out of conviction and habit: I wrote a thousand words a day, if at all possible. Writing was a way of life, a way of seeing and processing the world, etc.) Even though other students had long ago discovered my webpage and had mostly already forgotten about it, a handful of parents in a new class subsequently discovered it and raised a God-awful stink. As one administrator subsequently put it: "These people need to get a life! They need to get jobs! They have too much time on their hands!" The administrator continued: "They are scouring large portions of your webpage and putting everything you wrote under a microscope. Some have printed out hundreds of pages of text." This administrator concluded, "Be advised. Be very careful."

It was strange. For a long time my personal webpage had been common knowledge at school; students occasionally made reference to it, as did some parents when I spoke with them. I had figured if there was anything in it terribly objectionable, someone would already have objected. But now suddenly a storm had broken out and it took me unawares. I received a phone call on a Saturday afternoon instructing me to attend a meeting with top administrators the following Monday morning before school. Over the next few days at that meeting and at others there were frank exchanges of views; but I was not about to budge. "What if I tell you I am a gay Buddhist. What are you going to think of me?" an administrator asked. "That's very interesting, but I don't care very much," I replied. "So you are a gay Buddhist? So what? Happiness to your sheets!" Further explanation was proffered to me. "Schools like Milken, Richard, are terribly concerned about their image and who represents them. I know of one school that would fire a teacher for dressing a certain way or looking at someone wrong," another administrator explained. "I am not sure if you want to make this into a crusade. Remember what happened to Joan of Arc!" I countered angrily: "And still we sing her praises!"

I was very alarmed. The panic and hysteria had set in for real, and parents who knew nothing about the Internet and had not even seen my webpage personally joined in calling for my head. In fact, they seemed to clamor the loudest. I think they were the most alarmed, as they knew the least about computers and the World Wide Web. These parents got on the phone with each other, their anxiety gained momentum and increased exponentially after each conversation, the uproar acquired quite a froth, and a mob mentality arose. That which we do not understand, we fear. One irate parent even called a rabbi on the Sabbath to complain, angering that rabbi. The good at Milken was very good, the bad was not so bad, but the ugly could be plenty ugly.

The conspirators demanded a special public meeting with the administration dealing with my webpage and what to do about it. The school at the highest levels took a good look at my webpage, thought it over, and decided this was foolishness. "There will be no witch hunt!" came the judgment from up above. Still the complaints did not go away. "What about Mr. Geib's webpage?" a few parents continued to complain at monthly parent meetings. "What do you want us to do? Do you want us to fire Mr. Geib?" came the exasperated response. "We are not going to do that!" These parents, powerful and affluent, were unaccustomed to hearing the word "no." The answer left them unsatisfied. They paid such-and-such dollars per year in tuition and wanted what they wanted. I suspected the controversy came to be less about the morality of my webpage than a struggle between school and certain parents over power and control. Who was in charge?

So I watched every single word I said. I went to work every day feeling very much embattled. But my webpage was the quintessence of who I was. It was my very soul distilled into words, images, thoughts, and emotions. I had no children of my own, but the webpage was (in Plato's words) my "soul child." I had grown and nursed it for years with the utmost loving care and attention. Saying exactly and honestly what I think and feel in so public a manner had long since opened me up to the harshest criticism. I got hate e-mail almost daily. Street thugs and political extremists had threatened to kill me and could take their best shot, as far as I was concerned. If some knucklehead wanted to find me he could; I was hiding from nobody. I called it exactly as I saw it in my webpages, regardless. I had long since come to this conclusion. And so the hell if I was going to take down or alter them because of a handful of menopausal housewives from Encino!

My Irish was up, and I settled in for whatever would come next. From the president on down (re. Clinton-Lewinsky scandal) Americans coached their language in half-truths and hypocrisy and were less than candid in what they said. Most people feared offending some aggrieved interest in society, and so they employed a subtle but pervasive self-censorship as a form of self-protection: few spoke what they really thought in an era of "sensitivity" and "political correctness." I spoke, in contrast, exactly as I pleased towards the goal of being as honest and direct as I could. And I did not so not in private but in public. This freedom was a great feeling, almost priceless! It was something to fight for, even to die for!

But the episode crystallized certain objections my father, among others, had about my webpage. His father, my grandfather, had thought the ideal man kept his face strictly out of the newspapers and his name off his neighbor's tongue. "Fools' names and fools' faces appear in public places," my grandfather used to intone to my father; and my father repeated it to me in warning about my webpage. "Why go out of your way to attract controversy when there is so little to be gained and so much to be lost?" my father asked me. When two tigers clash, one is killed and the other is maimed. Why then even enter the fray? It is better to stay out of sight. Quietly but assiduously the ideal man acquired wealth to support his wife and family and therein lived the "good life"; the private life is where all value resided, according to my grandfather. The public life inevitably exposes one to gossip and controversy. It is damaging. Worse, it is corrupting.

I saw things differently. "The man is only half himself, the other half is his expression," claimed Emerson; and a private man without a public expression is only half a man, in my opinion. I would prove honest to myself and be wholly a man, both in private and in public - and most of all, in my webpages. I often felt like only in my webpages could I be most truly "myself." Nevertheless, I had no intention to cut a controversial figure or assume the mantle of rabble rouser; a record of my convictions and passions, I built my webpages strictly for my own pleasure - and as there was no thought given to pleasing Milken parents when they were christened, neither was there desire to offend. I wanted to capture as completely and artfully as possible my angle of vision of the world, my joy in philosophy, poetry, and art in general. I sought neither to curry favor nor to offend. I was sorry if my webpages upset some people, but I was not terribly sorry. I was not a politician running for office, after all.

But as a teacher I was a somewhat public figure, nonetheless. It was thus whether I liked it or not. I had known for years people would one day scrutinize what I said in my webpages and attempt to hold it against me. I was not stupid. Consequently, there was nothing in my webpages that I would not repeat in a crowded elevator or in front of an audience. I said nothing without careful consideration, but still I spoke my mind - and if obnoxious people did not like what I wrote, I frankly couldn't have cared less. So I believed then, so I believe today. I would accept the consequences. I had thought this through.

Enough said.

But then the polemic finally died away. As suddenly and quickly as the affair had erupted, it was seemingly forgotten. I was most relieved. There would of course come some other "scandal" for neurotic parents to obsess about, but the spotlight moved away from me. Many of my ex-students - those who knew me well - were up in arms and could not comprehend what was all the brouhaha in the first place. ("Parents can be so stupid!") Most of them had checked out my webpage with seemingly mild interest before moving on to Internet fare more interesting to teenagers. And the students enrolled in my classes at the time, I think, were more embarrassed than anything else. The episode moved me to reflect philosophically on how exceedingly difficult and frustrating it must be as a school administrator to deal with such parents constantly. I was told that they were relatively small in number, and that it was important not to let them poison you against all parents. Most parents were supportive, appreciative, and reasonable; but if the more numerous, the good parents were also the less vociferous. One has to look at the big picture, I was told. This was good advice, and it proved a good lesson that I learned therein: never let the shitbirds get you down. Never let them see you sweat, and never forget that no matter how hard you try you cannot satisfy everyone. It was a lesson applicable not only to education but to the wider arena, too. It was a lesson for all who dealt with the public. Listen to the criticism, give it a fair hearing, come to a decision, and then move on.

I was heartened months later in my final exit interview with Head of School, Dr. Rennie Wrubel. "I know this year has not been easy for you in many ways. In particular, I mean with that group of parents and your personal webpage," Rennie explained to me. "But I just want you to know that I never for one moment considered firing you." It was reassuring to hear. It meant a lot to me. One of the indictments made against my webpage was that I admitted in my likes/dislikes section to enjoying "women wearing button-down Oxford shirts - and nothing else!" "Well, of course he does!" Rennie replied animatedly more to herself than to me. "He is a normal heterosexual man!" It is one thing to talk the talk of free speech in a school. It is another to walk the walk. That the Milken administration and involved Temple elders backed me up so strongly against a small cabal of hostile, fixated parents speaks volumes about the nature of the place. In fact, I can hardly think of a higher compliment to an institution dedicated to learning and the life of the mind. I wondered how I would have fared at the hands of fundamentalist Christians in a place like Kansas. Would a school in the Bible Belt find a spine as did Milken? Or would they cave under pressure? I was an obviously competent teacher with a slew of enthusiastic work evaluations behind me, and I had support in the community and among the student body. But what would have happened if I were a beginning teacher? It was a delicate, dicey question.

Yet the final decision did come down my way, and the episode was far from entirely negative. I later came to understand just how many Milken parents had come forth vigorously to defend me without my knowing it. That made me feel good. My students were of course great. Colleagues on the faculty had pledged to quit if I were fired. But, in a sense, the damage was already done in this ridiculous, pathetic tempest in a tea cup. The incident served to unpleasantly tinge my time at the middle school and made my final decision to leave easier.

But an excellent school is an excellent school by any other name (even when it is named after someone with so cloudy a past), and I left Milken Community High School respecting it as such. Through the good, the bad, and the ugly I grew enormously as a teacher. Month after month I worked tirelessly to hone my skills as a teacher. My fellow teachers were experienced and talented and I learned much from them. The administration ran a tight ship. They could distinguish clearly a bad teacher from a good one and would fire incompetent instructors. My bosses saw clearly my potential and gave me expensive training integrating computer technology into lesson plans. My last year I taught students only part-time, while I spent the rest of my days developing model lesson plans and working closely with the Milken Family Foundation to help other teachers to integrate technology into their classrooms. It was an experience that drastically improved my teaching skills and for which I am very grateful. I left also with a warm feeling towards the community. Most Milken students were intelligent and respectful and came from sophisticated backgrounds and loving educated families. Most were well on their way to professional careers and (I will dare to hope) happy lives. The school was providing an excellent enriched education for its students. I enjoyed spending my days with them, and the majority of my students felt the same towards me. But Milken was not a perfect fit. It was not "right" for me.

Let me move more to the point. I have already spoken at length about my dissatisfaction with Los Angeles and how I had long desired to leave and so, esteemed reader, I will not tire your ear with the repeating of it. The only reason I was still in LA was because of my happiness at Milken Community High School. If not for that, I would have long since been gone. Yet, it was not enough.

So let me return to my letter of resignation where I further explained to Rennie:

But I grew up in the suburbs where the public schools are excellent and private schools consequently almost non-existent. The Third World system of education in Los Angeles where the vast masses sit warehoused at inferior public schools in the lowlands and the elite attend expensive private schools up in the hills has never sat well with me. I am a product of middle-class America and desire to return to a middle-class environment. After eleven years in the city of Los Angeles I want to invest my adult life in a place with more open land, clean air, and sense of community and friendliness. Every morning for almost three years on my way to work I have sat stuck in pernicious L.A. freeway traffic, looking around me surrounded by strangers (re. my "neighbors") sitting in shiny new BMW automobiles talking on their car phones oblivious to the rest of the world. I don't want to do that anymore. I have found Los Angeles to be a vibrant, exciting place to be a young adult. It has less to offer mature adults who want to invest in a community, start families, and build a sense of "home."

Freshly transplanted from upstate New York, it seemed almost your first official act as "Head of School" at Milken was to offer me a job. Adjusting and learning at work over these past three years, I have sometimes wondered how you were also adjusting and learning on the job. I wondered if, in the face of the maelstroms and pressures that without a doubt swirl around an important high profile job like yours, you looked back at your old position as principal of a quality suburban public school like Byron Hills with fondness and longing. Well, I am off in search of my own Byron Hills. Wish me luck.

Perhaps this land of gentle moderation and bucolic idyll existed only in my dreams, but I gambled otherwise and moved north to the rolling foothills of the Ojai Valley and surrounding Ventura River region in search of a happy middle ground.

![]()

![]()