Berlin, East and West:

A Crossroads of History

September 21, 1991 We took the night train from Amsterdam to Berlin and slept in our seats and this is not a method which provides for good sleeping; I awoke in Berlin feeling groggy and tired with little chance to freshen up. We spent the day making a whirlwind tour of West Berlin. There is so much history (recent) here, and being able to go into East Berlin is nothing short of miraculous. The Brandenberg Gates area is now an open air market specializing in Soviet military mementos. I bought a Soviet paratrooper watch for U.S. $18. While all of Europe suffered devastation from the Nazis, great parts of Germany are simply no longer there. The area around the Brandenberg Gates and the Reichstag used to be the center of political life in pre-war Germany - the heart of Germany. Today they are a series of empty fields. We visited the site where the Gestapo Headquarters building used to stand; now it is also an empty 1/4 mile of city block with a lone sign declaring its former use. No one builds there.

I also visited the Old Jewish Cemetery that was destroyed by the Nazis during the kristallnacht and is now a lone and entirely peaceful and quiet park of the type so common to East Berlin (and East Europe in general - semi-neglected is a better term). I would not have been able to guess the history of this park if I had not had a travel guide and an oblivious bystander would assume the park is no more than a small unremarkable urban park. As I sat quietly on a bench, I was struck how different it must have looked in the days of the Nazi insanity; this site of odious violence and hateful invective stands tranquilly oblivious to the passions and contentious strivings of men and of the sins of the past. To my mind, this is as it should be, for it makes one realize how inconsequential man really is in the scheme of things and how the deeds of men only really matter to men. In the Old Jewish Cemetery in 1991, the pigeons rule docilely and the trees sway gently in the breeze quite unconcerned with man's past misdeeds. They could care less about man and the stupidity and vanity of homo sapiens. To the park, it all happened in a heartbeat and the tranquility mocks the memory of frenzied Nazis digging up Jewish graves.

A synagogue burns in Siegen, Germany, on November 10, 1938 (Kristallnacht).

West Berlin is gaudy and lively. It is the perfect example of how West Germany rebuilt itself into a successful free nation. We stayed in a pension near the Ku Damm which is highly commercial and replete with neon lights. In striking contrast, the bombed out Kaiser Wilhelm Church is now a religious memorial to peace. I have heard it said that Germany is the country in Europe most like America and I think there is truth in this. There is something about the hustle and bustle of Berlin that puts me off, perhaps it is a little too much like home.

I visited Checkpoint Charlie, which recently became obsolete and a superfluous historical anachronism before its official removal. The Checkpoint Charlie Museum was both powerful and fascinating. There are examples of all the disparate ways in which East Germans tried (both successful and unsuccessful) to cross the wall: balloons, home-made airplanes, tunnels, etc. It would be hard to underestimate how bitterly the Berlin Wall divided Germans or how much it was hated. I saw more than one German crying at the Brandenberg Gates, incredulous at being able to visit the place unmolested. I felt quite proud at the U.S. role in keeping Berlin a free city. It is one of the few times that we were really appreciated. During the blockade there were some extremely dicey moments, and at Checkpoint Charley U.S. and Soviet tanks squared off. In this climate, it is easy to understand why President Kennedy with his unequivocal support seemed like such a god to West Berliners - and to Europeans in general. His assassination shocked the Europeans as much as it did Americans.

Hear

President Kennedy's Famous Speech in Berlin!

251 kb .wav

An American Army patrol checks on East German borderguard activity

near Ringstrasse by the Country Wall.

The wall area was constantly tense and many times East Germans were shot down mere yards away from freedom, right under the noses of U.S., French, and British guards. There were even a few instances where East German soldiers threatened to shoot escapees and only stopped when NATO soldiers pointed their weapons at the E. German soldiers. What a terrible dilemma: to be under orders not to fire unless fired upon under the justification of avoiding a general conflagration and yet be powerless to prevent a murder right in front of your eyes (and to be so clearly capable of stopping it). There is the tension between what is smart and what is right.I also paid a visit to the Plotzensee Memorial, which is the prison and execution chamber of the Third Reich. I had all along been wondering to myself, "Where are all the honest Germans of conscience during Hitler's rule?" The answer is: they were in Plotzensee. It is a large prison with the site of executions in a neat little brick house outside the main walls. There is a beam on the ceiling with eight hooks for the hanging of persons by the neck, as well as drapes that can be pulled across to hide the bodies from the next round of condemned men. During the war, there was also a guillotine. Thousands were executed there, sometimes a hundred in one night. All opposition (German) ended up in Plotzensee and were inevitably executed, often after a stay of many months. There were many admirable men who died there, and reading of the accounts of their final moments and parting words was poignantly touching, to say the least. It is one thing to read of tragedy and heroism in the neutral surroundings of one's home, and quite another to try to re-live it on the actual site with the relevant devices still in place. Admittedly an indefensibly subjective experience, one can almost hear the ghosts of the past pleading their case.

I should like to think that if I were a German citizen in the Third Reich I would have the courage to be in Plotzensee - clearly that is where people of good conscience in Nazi Germany belonged! Too many Germans took the easy way out and remained silent in the face of infamy. To be silent in such circumstances is to be an accomplice to mass murder of the most crass nature.

Many men of conscience who died defiantly in that little cabin because of opposition to the Nazis and it restored a certain level of respect for the Germans of that era. It also deflated my perception of the Nazis as able to completely mesmerize an entire population. From the view of Plotzensee, they look no better than any other totalitarian government that need resort to murder to silence an idea. That view is particularly unflattering and effectively illuminates the bottom line of Nazi rule: total lawlessness and brute force - a boot kicking in a door in the middle of the night. Whatever can be said about the discipline, efficiency, and honor of much of the German Army, one cannot forget how the Nazi Party started out as a collection of rowdies and beer hall brawlers in search of a weaker opponent. It never moved much farther from this ignominious beginning.

The Nazis in ideology and in practice were no lovers of erudite and learned men. Look at the following quote by German writer Hanas Johst in his book Schlageter: "When I hear the word 'culture' I reach for my revolver." (Johst was later killed in WWII) Or according to Nazi leader Martin Borman, "Education is a danger... At best an education which produces useful coolies for us is admissible. Every educated person is an enemy." As Nazi Propaganda Minister Paul Goebbels said, "Intellectual activity is a danger to the building of character... The intellect has poisoned our people. How much elementary strength in that fellow compared with sickly intellectuals." or "Critics are morbid, degenerate, democratic individuals. Some even say the Jew is a human being." Or as Hitler himself quoted by John Gunther said, "A violently active, dominating, intrepid, brutal youth is what I am after... I will have no intellectual training. Knowledge us ruin to my young men." No wonder so many of the German men of letters and learning fled the country (Thomas Mann) while others (Victor Frankl) found themselves in concentration camps.

Adolf Hitler! What a small-minded and angry man! What an obscene government!

This effectively makes the law an instrument of oppression and violence. All these execution writs I have seen here in museums deriving their authority in "the name of the German People!" I am so tired of People's Courts and summary justice and death in the name of the People, God, etc., that has so besmirched the 19th and 20th centuries. French scholars would have us all remember the Declaration of the Rights of Man as the legacy of the French Revolution, but I remember the Terror and the dark and towering figure of Robespierre; he was the first and not the last man to figure that a greater happiness of mankind must be brought about by a pitiless destruction of the "enemy," and that the absolutely harshest measures were to be singularly pursued if a paradise were to be assured. As if the degree upon which the utopia is deserved depended upon the amount of brutality committed in its name, with each death a sort of badge of honor and an emblem indicative of commitment to the cause. I would almost prefer to be killed by reason of monarchical capriciousness - there is less hypocrisy. It is a perverted ability of intellectuals to be able to convince themselves that any sort of good can come from such actions. "The lawlessness of Hitler's Germany, beneath a thin veneer of legal forms, was absolute. As Goering put it, "The law and the will of the Führer are one." Hans Frank: "Our constitution is the will of the Führer."

Paul Johnson

Modern Times

The Symbol of 20th Century Totalitarianism: A Political Prisoner in a Death Camp.

The Germans and German culture are so paradoxical. The frenzied ravings of Nietzsche and the principled moral dignity of Kant. The integrity and brilliance of Erwin Rommell and the cold bureaucratic cowardice of Himmler and the "final solution." The genius of German thought and science and the ignominious slaughter of invasion and domination from the Vandals on up to Hitler. The Germans have been responsible for some of Western Civilization's most elevating achievements as well as some of its most heinous crimes. They are capable of almost unparalleled brilliance and courtesy as well as the most blatant tactlessness and cruelty.It seems to me a most unique German phenomenon that respected and highly-educated scientists would unthinkingly and quite un-hypocratically conduct fatally obscene medical experiments on captive Jews. An "undesirable element" may be put in a concentration camp where he will be cruelly and unceremoniously worked to death. But upon his expiration, a dutiful letter will be sent to his relatives humbly indicating the date and cause of death, how medical treatments were ineffective, how the burial costs will be covered by the State, etc. It is especially confusing to try to find the connection between the impressively organized democracy of modern Germany which I see before me and the Germany of 1939. Although they are both a uniquely German phenomenon, it is hard to reconcile the malevolent legacy of Auschwitz and the kristallnacht with the elevating piousness of a Bach chorale, so steeped in humble Protestantism. How strange to be so technologically advanced and efficient and so scientifically precise, yet so blind to the uses and consequences of such skills? The supra-efficient war economy that fought the world to a standstill was the same country that organized in an equally efficient manner a mass-slaughter of the most crude nature.

"The German revolution will not prove any milder or gentler because it was preceded by the Critique of Kant, by the Transcendentalism of Fichte. These doctrines served to develop revolutionary forces that only awaited their time to break forth. Christianity subdued the brutal warrior passion of the Germans, but it could not quench it. When the cross, that restraining talisman, falls to pieces, then will break forth again the frantic Beserker rage. The old stone gods will then arise from the forgotten ruins and wipe from their eyes the dust of the centuries. Thor with his giant hammer will arise again, and he will shatter the Gothic cathedrals.......and this was written by Heinrich Heine over a hundred years before the rise of Hitler and Nazism - from a German poet whom I had always known for his love poetry! Is it possible that the genius of Bach was always only a few steps away from the Germanic barbarians fighting the Roman legions to a vicious standstill on the borders of civilization?"Smile not at the dreamer who warns you against Kantians, Fichteans, and the other philosophers. Smile not at the fantasy of one who foresees in the region of reality the same outburst of revolution that has taken place in the region of the intellect. The thought precedes the deed as the lightning the thunder. German thunder is of true German character. It is not very nimble, but rumbles along somewhat slowly. But come it will, and when you hear a crashing sound as never before has been heard in the world's history, then know that at last the German thunderbolt has fallen..."

I have spent much time thinking of Nazism and its results, of German history from the marauding barbarian tribes on up, what I have personally seen in Germany and of Germans, and what I have read and heard of German intellectual thought and literature -the inconsistencies and paradoxes are enough to make my head want to explode! My American-Jewish friends hold a deeply entrenched hate of Germany and things German that transcends the rational and often sits just below the conscious. This is almost a defining aspect of the modern Jew: "Only an irredeemably sick culture could have perpetrated the Holocaust!," and "The Germans tried to exterminate us and we will never forget!" It is highly personal, and on a certain level Germany will always be the enemy of Jews everywhere. Forever. And with the advent of neo-Nazism in Germany today, everyone questions the trustworthiness of modern Germany. I cannot personally leave Germany with any kind of feeling that such a crime could again occur there. But I am sure I will leave here unable to explain or understand many aspects of Germany. For to visit Berlin is to meet history, both recent and distant.

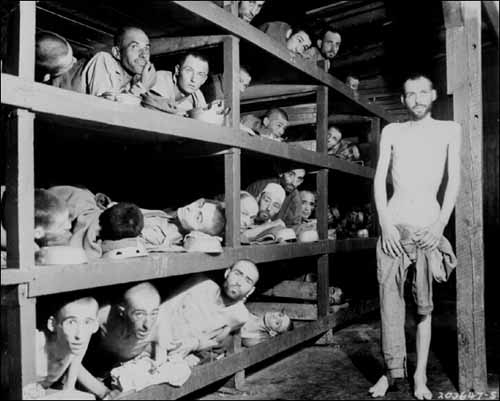

Gaunt holocaust death-camp victims await liberation by the Allies.

What is it about the German psyche that made the Germans so whole-heartedly support Hitler which produced the bloodiest war in history and the holocaust? Modern Germans remark upon how the worst excesses of the Nazis were carefully kept away from the public and that many Germans supported Hitler grudgingly out of anti-Bolshevism, or fear of anarchy. There is truth to this, but it does not, in my opinion, explain the substantial emotional support that Hitler tapped with his anti-Semitism and racial superiority. After all, Hitler carefully stated exactly what he was going to do when he took power in Mein Kampf, and then he did it. The German people has been warned. The German people were genuinely surprised that Hitler got them into a huge world war fighting almost everyone, and that they were personally getting the shit bombed out of them. It should not seem so surprising upon reading Hitler's bellicose pre-war statements, but I guess it is a matter of selective attention - seeing what one wants to see. Thomas Mann, writing after the war, rationalized a bit much when he claimed, "There are not two Germanys, an evil and a good one, which, through devil's cunning, transformed its best into evil." The Germans legally handed over totalitarian power to Hitler and by then it was too late to do anything, even if they had wanted to. I do not accept the Germans as mere victims of Nazi oppression, for Hitler was a uniquely German phenomenon and embodied the worst they have to offer. Perhaps the subject is more appropriate in the realm of deviant social psychology than in that of political science. The Germans accepted too easily the role of conqueror and master to lay all the blame on scapegoats.There is an arrogance to German thought which manifests itself in a sort of conquering evangelicism, ie. that the sin, evil, and corruption of the world would be erased if the superiority of German ways and wares were acknowledged. The German nation needs room to expand and it will take this land by virtue of the strength of German arms! There is a kind of German proto-mythological hero archetype which glorifies the barbarian blond conqueror of unworthy and corrupt races. It is like some majestic and unstoppable bird of prey whose inherent superiority gives it the right to act as a predator. It is true that modern Germany has publicly taken the bitter lessons of WWII to heart and is loudly un-militaristic and unthreatening. Perhaps the historical cycle of Frederick the Great to Bismarck to Wilhelm to Hitler to whomever is next has been stopped. But the German has historically moved to easily and unambivalently into the role of aggressor and conqueror for my comfort of my mind. Like a petulant child or neurotic mensch, Germany has always felt herself misunderstood and unfairly accused. Postwar Germany notwithstanding, democracy never took root much in Germany. Bismarck summed it up well: "The great questions of the day will not be settled by resolutions and majority votes - that was the mistake of the men of 1848 and 1849 - but by blood and iron."

One evening, I was at a sidewalk cafe ordering some sausages for dinner where a couple of older German men were eating also. They were inebriated, to say the least. One of them inquired if I was American and then launched into a speech about how great America and Americans are - going so far as trying to hug me! He said that Germany was "no good. Good only for war!" Another elderly gentlemen who claimed to be an old army officer came up and rebuked him, even clicking his feet together in some sort of exclamation. This sounds like an implausible scene but I swear to God it happened! And yet I have many times met native Germans personally and have been nothing but impressed by their courteousness, refinement, and erudition. To attempt to talk about Nazism with them would be taken almost as an insult, "That is all in the past." And yet the past always continues to influence the present as well as the future.

And now Germany is unified and taking a more active role in the political life of the European Community. This is a basic change in the post-war NATO collective security arrangement designed to "Keep the Americans in, the Russians out, and the Germans down." We Americans have been urging the Germans to play a political role more commensurate with their economic strength, and now some are worried about renewed German domination of Europe, even if it is only of an economic nature. All this, of course, happens at the expense of the French. There seems to be a perpetual tug of war between Paris and Berlin as to which is the heart of Europe. Paris is the cultural center with all the charm, refinement, and art of the more prosperous Western Europe while Berlin is the geographic heart of greater Europe including the Slavs and the larger number of people and material resources. The Parisians resent the greater physical power of the Berliners, and the Berliners supposedly hold an inferiority complex as to the beauty, charm, and respectability of Paris.

Berliners celebrate the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989.

Today organizations like the Simon Wiesenthal Center and other Jewish organizations seek to keep the holocaust and Germany's war guilt fresh in everybody's mind in the hopes that people will never forget what happened. I think the chances of people forgetting the Nazis and the Holocaust slim whether the Jews constantly remind people or not. And I wonder at the wisdom of keeping fresh in our consciences all these war crimes which are already half a century old. Ripping old wounds open anew I suspect militates against the spirit of reconciliation and forgiveness in Europe.We could use less emotional reactions and let the soothing balm of time heal the scars of the past. One of my best friends is Jewish and he would not ever consider visiting Germany, reading German authors, or listening to the music of Wagner, etc. "What a waste!" I think. For emotional reasons, he is closing himself off to many beautiful and worthwhile things which come from German culture. For my friend, the emotions of the issue run so strongly that for him to be German is to be evil. He feels so strongly about it that he will not even consider another point of view. And he has even more contempt for the Poles who didn't kills Jews but handed them over to the Nazis! And yet it is becoming rarer and rarer to even encounter Germans or Poles who were even adults during WWII! To suffer the sins of the fathers on the sons makes no sense; perhaps we should let the Third Reich die along with those Germans who were old enough to remember it. This does not mean that we should forget it.

Only history will tell whether the decision to take the shackles off the German nation is a prudent one. I personally think it was an idea whose time had come. Yet to say that the Germans are an enigmatic people is to understate things. I came here with questions and I will leave here with only more questions.

We went out one night here in West Berlin and had the worst luck in finding good bars. All we could find were lame discos with expensive beer and we even stumbled into of all places a gay bar. After spending too much money for not very much fun, we ended up drunk and Matt threw up in our room. It is not easy to understate how pissed and offended the girls were. I thought it was funny, but mostly because the girls freaked out so much.

The "alternative scene" is big in Western Berlin. I guess the West Berliners are exempt from the military draft and so the radical population is large. We stopped at the "Ex," an alternative bar and it was scary: lots of black and leather, militant murals of barricaded radicals firing guns at the police, men with guns everywhere, etc. These people call themselves "autonomns," and they are known for their cynicism - they have supposedly earned the unique distinction of hating almost everything besides themselves. The larger than life pictures on the walls are taken from the chaos of the Weimar Republic and I asked myself, "As if with their history, Germany needed more of this!" The night I was there, they were having an NOlympics party pertaining to the possible location of Berlin for a future Olympics. However, I later learned this sentiment came from the lack of affordable real estate in Berlin rather than from anti-Olympic convictions. It is reputed that these people have huge blow-outs with the police. There are a lot more radicals in Berlin than in Paris or London. Yet I have heard that Berlin has always had a very liberal populace, relative to the rest of Germany.

East Berlin is completely different than the West. It is largely untouched since the War, and this is both good and bad. It is good because much of the pre-war German grace is left intact and there is not much of the frenetic frenzy and chaos of West Berlin. One can see the former Stateliness of Berlin circa-1930 on the Unter der Linden Boulevard. The bad side (and it is very bad) is that the place is pretty much a dump. Except for a few dour parks, East Berlin is in an advanced stage of decay. Most of the buildings are falling apart, and some still have bullet holes in them from 50 years earlier!

It was very strange to be walking where only a few years before the dreaded East German secret police prowled. From the nasty days of the Cold War, "East Berlin" is a term synonymous with fear and menace, an omnipresent police and a pitiless scrutiny. From numerous works of fiction and non-fiction I've read in my childhood and later, East Berlin is the dreaded arena of shadowy covert actions with agents looming under the threat of violent discovery and brutal interrogation under some sadistic interrogator. All that is gone now, and to me it is an optimistic testament to the ability of man to change his society for the better. During my visit of 1991, the most striking aspect of East Berlin was its quiescent un-ostentatiousness.

The heart of East Berlin lies around the area of Alexanderplatz and what is supposed to be the center of East German socialism. There is a large radio tower which can be seen from the west and a statue of Marx and Engels centered in the middle of a group of portraits of socialist slogans and propaganda. Perhaps the most poignantly powerful thing I have seen in Europe, the hands and mouths of these two working class heroes have been painted red and the blood drips down onto the ground. We also visited the Pergomonmuseum which boasts an almost perfectly preserved Alter of Zeus built in 180 B.C. in Greece. It is hundreds of feet in diameter and is exactly what I had always pictured a Greek temple in terms of how its size and splendor symbolize the perfection, power, and beauty of the gods. Before WWII, the area around the Unter der Linden street was one of the classiest and ritziest streets of Europe. It leads west from Alexanderplatz to the desolate fields surrounding the Brandenberg Gates. Across from the museums is Bebelplatz, a square where the Nazis held their book burnings. The old burned out Jewish Synagogue for years stood unrepaired with a sign in front that reads, "Never forget this." Appropriately, I think, to the new spirit of German reconciliation, the temple is being rebuilt. However, the powers that be have found it necessary to post a policeman in front of the construction site.

The girls left us to go their own way and Matt and I took the "S Bahn" out to the Treptower Park and the Soviet War Memorial. Impressive, even in the dramatic and large scale-style of the Russians, the monument must be a 3/4 mile in circumference dominated by a 100 foot tall Soviet soldier holding a child. One enters the memorial and looks between two huge red arches that frames the soldier a 1/2 mile away. Walking toward the soldier, there are pictures of the Red Army with quotes by Stalin carved on slabs of marble taken from Hitler's Chancellery. The monument is fabulous, as is the other Soviet Army memorial near the Brandenberg Tor. The Soviet Army did fight a valiant and heroic struggle against the Nazis but how arrogant to put such epic monuments up to oneself in a defeated foe's capital! It is like rubbing it in.

The Soviet legacy is large among the east although now nary a Soviet can be found in public. I think the future will prove the west (ie. the French, U.S., and British) as better remembered and judged in their role in post-war Germany, even though ironically there are no public monuments to them. Perhaps the whole episode was prognosticated by the fact that not a single German soldier at the end of WWII preferred to surrender to the Soviets rather than to the Americans, British or French.

The Soviets always attempted to identify Nazi Germany as the ideological arch-enemy of their political system. The Marxist-Leninists are located on the left of the political spectrum and the Nazi fascists on the right, the conventional thinking runs. And then after WWII the Soviet Union tried to paint the Western democracies - especially the United States - with the same fascist paintbrush. In truth, the Soviets and Nazis had much more in common with each other than they ever had with the parliamentary democracies. They were both totalitarian nightmares with a small group of men - "Nazis" and "Bolsheviks" - terrorizing/leading their countries with an ideology as justification for murder: the superiority and violence of race on the one side; the superiority and violence of class on the other. They both believed that in order to improve mankind they had to murder a portion of it - like a doctor surgically removing a cancer for the greater health of the patient. As Paul Johnson described:

"Once Lenin had abolished the idea of personal guilt, and had started to 'exterminate' (a word he frequently employed) whole classes, merely on account of occupation or parentage, there was no limit to which this deadly principle might be carried. Might not entire categories of people be classified as 'enemies' and condemned to imprisonment or slaughter merely on account of the colour of their skin, or their racial origins or, indeed, their nationality? There is no essential moral difference between class-warfare and race-warfare, between destroying a class and destroying a race. Thus the modern practise of genocide was born."Sir Isaiah Berlin also put it well:

"The divisions of mankind into two groups - men proper, and some other, lower, order of beings, inferior races, inferior cultures, subhuman creatures, nations or classes condemned by history - is something new in human history. It is a denial of common humanity - a premise upon which all previous humanism, religious and secular, had stood. This new attitude permits men to look on many millions of their fellow men as not quite human, to slaughter them without a qualm of conscience, without the need to try to save them or warn them. Such conduct is usually ascribed to barbarians or savages - men in a pre-rational frame of mind, characteristic of peoples in the infancy of civilisation. This explanation will no longer do. It is evidently possible to attain to a high degree of scientific knowledge and skill, and indeed, of general culture, and yet destroy others without pity, in the name of a nation, a class, or history itself. If this is childhood, it is the dotage of a second childhood in its most repulsive form. How have men reached such a pass?"In all this, the Bolsheviks and Nazis were very similar - if not identical. When the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany finally (inevitably?) went to war against each other, it was with the passion of two thieves after a falling out or blood cousins in a bitter civil war who hate each other excessively and intimately and are capable of any barbarity. Serious differences between the Nazis and Soviets? I hold them to be cosmetic while the spirit of the two regimes was similar. I hate the Third Reich was one might hate mob violence and thuggery. I hate the Soviet Union as one hates a lie. It all comes down to the difference between a liberal and illiberal society. Betrand Russell defined it well: "The fundamental difference between the liberal and the illiberal outlook is that the former regards all questions as open to discussion and all opinions as open to a greater or lesser measure of doubt, while the latter holds in advance that certain opinions are absolutely unquestionable, and that no argument against them must be allowed be heard. What is curious about this position is the belief that if impartial investigation were permitted it would lead men to the wrong conclusion, and that ignorance is, therefore, the only safeguard against terror. This point of view cannot be accepted by any man who wishes reason rather than prejudice to govern human action."

Hitler was honest enough about it when he wrote in Mein Kampf: "Either the world will be ruled according to the ideas of our modern democracy, or the world will be dominated according to the natural law of force; in the latter case the people of brute force will be victorious." Lenin was attributed to have said, "The worst enemies of the new radicals [Bolsheviks] are the old liberals." The Third Reich was bombed into the ground in 1945, and today the Soviet Union is descending into its grave under the heavy weight of its corruption, mismanagement, crimes, and tyrannies over more than 70 years. Good riddance to them both!

Matt and I had a very pleasant beer in an out of the way, hole in the wall East Berlin bar. The people were generous and our "Americaness" was still novel to the owners who amicably made jokes of our height and mimicked the motions of throwing an American football. Blissfully, they spoke no English. The beer was excellent, cheap, and served in a beautiful pilsner glass which is so common in Germany. Matt bought the glass on the spot from an astounded proprietor. This little incident typifies the differences between East and West Berlin: expensive and semi-touristy bars in the west and cheap "dives" in the east. Another good example of the differences is a train ride through Berlin in the middle of the night, with the west brightly lit up by street lights and buildings and the east almost completely dark.

I felt a little bad enjoying the cheap prices so much in East Berlin. As British punk rocker Johnny Rotten described his time in East Berlin: "A cheap holiday in other people's misery."

![]()